Fat Cars: Report Reveals What We Already Know About Vehicle Weight

Despite hearing corporate and government actors praise the merits of electrification for years, a sobering reality appears to be taking hold. Despite boasting exquisite torque delivery and the ability to benefit from at-home charging, the public is beginning to doubt their status as economical and environmentally sound transportation. EV prices haven’t fallen as promised, battery mining turned out to be rather contentious, and the vehicles themselves continue getting heavier — resulting in some record-setting curb weights that are likely serving to undermine roadway health and automotive safety.

While the weight issue may be more pronounced among EVs, it’s hardly limited to them. Just about every modern vehicle outweighs its ancestors by a staggering amount and a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) study has claimed that an extra 1,000 pounds increases the chance of crash fatalities between vehicles by 47 percent.

The United States actually has a regulatory environment that promotes larger vehicles, particularly pickup trucks and SUVs, as they’re not subject to the same stringent emissions regulations as smaller passenger vehicles. Your author covered the topic a few weeks ago and has likewise complained about how modern automotive design seems to have become a snake eating its own tail.

Manufacturers hoping to adhere to modern regulations are prioritizing extremely heavy EVs that arguably pose more of an ecological concern than the lightweight economy vehicles they were supposed to replace. Meanwhile, CAFE loopholes added during the Obama administration have encouraged the automotive industry to prioritize larger combustion vehicles, resulting in a majority of modern-day automobiles being far heavier than their predecessors. Novel safety requirements also contribute to this trend.

While the above has a tendency to advantage newer cars in the event of a crash, it often places older vehicles at a safety disadvantage. Recent years have shown an uptick in fatal car accidents, with the likely culprit being a combination of sizing/weight disparities, widespread implementation of distracting infotainment systems, poorly maintained roadways, and increased substance abuse. A few of those factors are totally out of the industry’s control and even those that aren’t are heavily influenced by decisions made by the government.

But there’s a good bit of data showcasing how undesirable particulate matter has risen along major roads and a lot of speculation as to why it probably pertains to weight. Heavier vehicles need larger brakes, which results in those vehicles producing more brake dust. Heavier vehicles also tend to come with larger tires and shed more of the material while rolling.

According to Automotive News, experts are increasingly worried about the results of these kinds of studies. If the National Bureau of Economic Research turns out to be correct about increased average vehicle weights leading to surging fatalities, then we’re about to be in some serious trouble. Worse still, EVs don’t really have as many avenues to trim their belt line.

Whereas combustion vehicles have porked up due to an overall increase in sizing and standard features, electric vehicles currently weigh a lot primarily due to battery implementation. EV batteries are exceptionally heavy and many models have already embraced a lot of other lightweight components in an effort to offset that mandatory heft. Sadly, there’s only so much that can be done without sacrificing other aspects of the vehicle’s performance.

From Automotive News:

"It's a vicious cycle," said Sam Abuelsamid, e-mobility analyst at Guidehouse Insights. "If you have a 9,000-pound vehicle versus a 6,000-pound vehicle, you need bigger brake rotors and calipers. You've also got to have heavier wheels and tires as the vehicle goes up in weight."

Besides the heavy batteries, EVs have gained weight because they are over-engineered for safety, according to experts.

"No one wants to have a fire, and no one wants a vehicle that isn't crashworthy," Detroit teardown and cost guru Sandy Munro told Automotive News. "There is over-engineering, and it's being done to ensure that if something does go wrong that lives won't be in jeopardy."

"If you look at the [EV] skateboard chassis and squint, it looks a lot like a body-on-frame with a top hat," Munro continued. "There's not much we can really do to reduce weight when you move to a skateboard, which has to have quite a bit of structural integrity because it is carrying the load."

Modest weight saving could be accomplished by removing some of the sound-deadening materials, shrinking the battery, and yanking out some of the sensing equipment required for advanced driving aids. But then you’d be left with low-range electric with none of the trendy tech and some of the worst NVH issues imaginable. People wouldn’t go for it on combustion vehicles and assuredly wouldn’t on an allegedly premium EV.

The obvious solution is for the industry to continue improving battery efficiencies by every appreciable metric. It’s an issue the whole world has been working on for years. But it’s not something that has progressed at a pace that has allowed electric vehicles to surpass combustion cars in terms of overall convenience. It has also ensured electrified autos carry around higher price tags simply by nature of having more materials going into their construction.

Still, both types of transportation are suffering from a severe weight issue these days — the engineers working on EVs simply have fewer weight-saving options at their disposal.

Ned Curic, Stellantis' chief technology officer, told Automotive News Europe that the situation "is not good for the environment, it's not good for resources, it's not good for efficiency."

"It frustrates me," he said, "that all of our cars — for the industry as a whole — are just too heavy. The cost is becoming unaffordable for the middle classes."

Creeping automotive pricing has resulted in regular people turning away from the new vehicle market as the economy worsens. The average age of cars on U.S. roads is now at record highs (12.5 years) and automakers continue culling the smallest and most affordable models from the lineup. A perfect storm of ham-fisted government regulations, widespread economic mismanagement, and short-sighted industry decisions have created a situation where millions of people are trying to nurse older models for the sake of saving money — cars that cannot hope to compete with their heavier modern counterparts in a crash and may ironically produce less pollution in a variety of scenarios.

Originally published in 2011, the NBER study goes into all of the above without focusing on powertrain types. But it has seen renewed interest this year as more people seem to be noticing the mounting issues associated with modern vehicle designs. While it also dabbles in mileage taxes, the paper is chiefly concerned with how variances in vehicle weight and shape impact overall safety. Some of its conclusions actually exacerbated the issue, as the study supports the "footprint-based" emissions standards that ultimately created regulatory loopholes in U.S. CAFE standards that have resulted in manufacturers prioritizing the manufacturing of increasingly large vehicles.

Whoops.

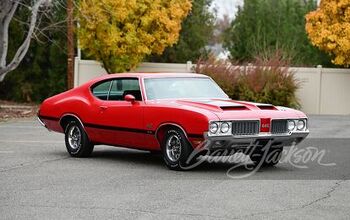

[Image: General Motors]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to the truth about cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

A staunch consumer advocate tracking industry trends and regulation. Before joining TTAC, Matt spent a decade working for marketing and research firms based in NYC. Clients included several of the world’s largest automakers, global tire brands, and aftermarket part suppliers. Dissatisfied with the corporate world and resentful of having to wear suits everyday, he pivoted to writing about cars. Since then, that man has become an ardent supporter of the right-to-repair movement, been interviewed on the auto industry by national radio broadcasts, driven more rental cars than anyone ever should, participated in amateur rallying events, and received the requisite minimum training as sanctioned by the SCCA. Handy with a wrench, Matt grew up surrounded by Detroit auto workers and managed to get a pizza delivery job before he was legally eligible. He later found himself driving box trucks through Manhattan, guaranteeing future sympathy for actual truckers. He continues to conduct research pertaining to the automotive sector as an independent contractor and has since moved back to his native Michigan, closer to where the cars are born. A contrarian, Matt claims to prefer understeer — stating that front and all-wheel drive vehicles cater best to his driving style.

More by Matt Posky

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- W Conrad I'm not afraid of them, but they aren't needed for everyone or everywhere. Long haul and highway driving sure, but in the city, nope.

- Jalop1991 In a manner similar to PHEV being the correct answer, I declare RPVs to be the correct answer here.We're doing it with certain aircraft; why not with cars on the ground, using hardware and tools like Telsa's "FSD" or GM's "SuperCruise" as the base?Take the local Uber driver out of the car, and put him in a professional centralized environment from where he drives me around. The system and the individual car can have awareness as well as gates, but he's responsible for the driving.Put the tech into my car, and let me buy it as needed. I need someone else to drive me home; hit the button and voila, I've hired a driver for the moment. I don't want to drive 11 hours to my vacation spot; hire the remote pilot for that. When I get there, I have my car and he's still at his normal location, piloting cars for other people.The system would allow for driver rest period, like what's required for truckers, so I might end up with multiple people driving me to the coast. I don't care. And they don't have to be physically with me, therefore they can be way cheaper.Charge taxi-type per-mile rates. For long drives, offer per-trip rates. Offer subscriptions, including miles/hours. Whatever.(And for grins, dress the remote pilots all as Johnnie.)Start this out with big rigs. Take the trucker away from the long haul driving, and let him be there for emergencies and the short haul parts of the trip.And in a manner similar to PHEVs being discredited, I fully expect to be razzed for this brilliant idea (not unlike how Alan Kay wasn't recognized until many many years later for his Dynabook vision).

- B-BodyBuick84 Not afraid of AV's as I highly doubt they will ever be %100 viable for our roads. Stop-and-go downtown city or rush hour highway traffic? I can see that, but otherwise there's simply too many variables. Bad weather conditions, faded road lines or markings, reflective surfaces with glare, etc. There's also the issue of cultural norms. About a decade ago there was actually an online test called 'The Morality Machine' one could do online where you were in control of an AV and choose what action to take when a crash was inevitable. I think something like 2.5 million people across the world participated? For example, do you hit and most likely kill the elderly couple strolling across the crosswalk or crash the vehicle into a cement barrier and almost certainly cause the death of the vehicle occupants? What if it's a parent and child? In N. America 98% of people choose to hit the elderly couple and save themselves while in Asia, the exact opposite happened where 98% choose to hit the parent and child. Why? Cultural differences. Asia puts a lot of emphasis on respecting their elderly while N. America has a culture of 'save/ protect the children'. Are these AV's going to respect that culture? Is a VW Jetta or Buick Envision AV going to have different programming depending on whether it's sold in Canada or Taiwan? how's that going to effect legislation and legal battles when a crash inevitibly does happen? These are the true barriers to mass AV adoption, and in the 10 years since that test came out, there has been zero answers or progress on this matter. So no, I'm not afraid of AV's simply because with the exception of a few specific situations, most avenues are going to prove to be a dead-end for automakers.

- Mike Bradley Autonomous cars were developed in Silicon Valley. For new products there, the standard business plan is to put a barely-functioning product on the market right away and wait for the early-adopter customers to find the flaws. That's exactly what's happened. Detroit's plan is pretty much the opposite, but Detroit isn't developing this product. That's why dealers, for instance, haven't been trained in the cars.

- Dartman https://apnews.com/article/artificial-intelligence-fighter-jets-air-force-6a1100c96a73ca9b7f41cbd6a2753fdaAutonomous/Ai is here now. The question is implementation and acceptance.

Comments

Join the conversation

"The MPGe of an electric averages between 3x to 5x higher than the ICEv equivalent"

This is an apples to oranges comparison. Pure energy efficiency calculations not weighted for time are pretty useless when comparing these technologies. Energy transfers by moving electrons is way slower than energy transfers via liquid fuels. This energy transfer rate matters for many ICEv applications.

Posky's bias seems to increasingly be affecting his journalistic abilities (unless this is supposed to be an opinion article).