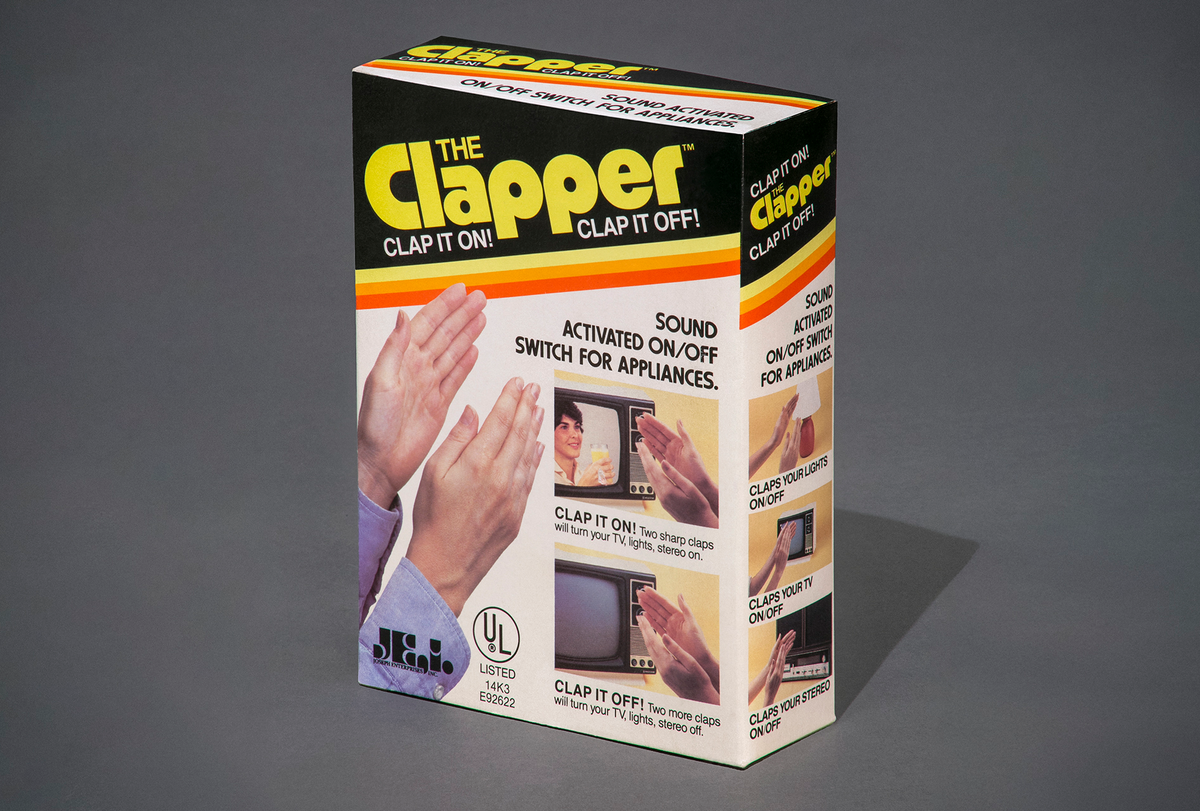

“Clap on! Clap off! Clap on! Clap off! The Clapper!” This 1980s earworm of a jingle touted a gadget to turn your lights, your TV, or any other electrical device on or off with the clap of your hands. If you watched any amount of American television back then, you probably saw the Clapper’s repetitious and yet oddly endearing ad, and perhaps you, like many others, felt compelled to give it a try.

Clap On Clap Off The Clapper (1984)www.youtube.com

The Clapper’s ad was the brainchild of Joe Pedott, a master of marketing who made people want gizmos they never imagined they needed—the Garden Weasel, the Ove Glove, the Chia Pet. In 1985, he was hired to sell the Great American Turn-On, the Clapper’s original name. The only problem? The device did not work. Indeed, when people used it to control their TVs, it tended to short-circuit the set.

Still, Pedott liked the idea of the gadget, and after the original investors went bankrupt, he bought the patent and hired engineers to fix the glitches. And so the Clapper was born.

The Clapper was a failure before it was a hit

Before I get into what made the Clapper so appealing, let’s first consider its predecessor. Despite its name, the Great American Turn-On was invented in Canada. In 1985, Peter Liljequist and Kou Chen filed a Canadian patent for an acoustic switch for turning lights and other appliances on and off. Then they approached Pedott to help market a gadget based on the switch.

Pedott test-marketed the Great American Turn-On at People’s Drug in Washington, D.C. While he was delighted that it sold well, the gadget itself failed catastrophically. Pedott also discovered that the company behind it was a sham, at least according to his oral history with the National Museum of American History.

After Pedott acquired the patent, which was assigned to his company, Joseph Enterprises, he hired Carlile Stevens and Dale Reamer to get the device to work. Eventually, they filed for a U.S. patent for the new and improved device. Stevens, a physicist, was a prolific inventor with more than 30 patents to his name. In the 1990s, he became known for his long-running legal battle against Universal Manufacturing Corp. for suppression of his patent for fluorescent light ballasts; he and his coinventor eventually won a jury award of US $96 million.

Most patents are dry as dust to read, but the one for the Clapper (U.S. Patent No. 5,493,618) is a chatty marvel. “In today’s society convenience is almost a necessity,” it states. “Many people will elect not to use an electrical appliance such as a television or light, if they must walk across a room to turn the television or light ON.”

To accommodate our essential laziness, manufacturers invented remote controls, only to be confronted by our ability to immediately lose them. “The requirement of possession [of the remote] in itself can be a major inconvenience,” the patent continues. “Often a person must walk across a room to retrieve the remote control unit, and frequently it may be misplaced, which, at best, requires extra time and effort to find.” Obviously, we needed an intervention. Hence the Clapper’s appeal.

The Clapper plugged into a normal, American-style two-prong wall socket and had two outlets, to plug in two different appliances—a lamp and a TV, say. Each appliance was controlled by its own series of claps. The Clapper also had an “away” setting that was activated by noise, designed to deter burglars while homeowners were on vacation.

The electronics were quite simple: a microphone to pick up sound in the room, a bandpass filter in the range of 2,200 to 2,800 hertz (the typical range of a handclap), a few triode switches, and a microcontroller. The U.S. patent gives an example of the sequence of tasks in pseudocode, and it also lists the ROM source code in an appendix.

The Clapper still had some problems. Some users clapped too slowly, others too softly. Sometimes there was too much background noise to distinguish a clap, other times the Clapper responded to an incidental noise that was not a clap. One dissatisfied reviewer complained that the Clapper didn’t work when its microphone was blocked by a large upholstered chair.

Yet, thanks to Pedott’s catchy jingle and ubiquitous low-budget commercials, the Clapper became ingrained in America’s kitsch culture, whether bought with purpose or as a novelty gift. Still sold today, the Clapper now comes in many flavors, including Star Wars characters, the public-TV painter Bob Ross, and the leg lamp from A Christmas Story.

Star Wars ‘The Mandalorian’ The Child Clapperwww.youtube.com

The secret to Joe Pedott’s genius

This column typically highlights the engineers who invent a product, but I think it’s also important to acknowledge the broader ecosystem that supports inventors and helps turn good ideas into successful products. This includes professional organizations, investors, patent attorneys, and marketers. In the case of the Clapper, it was Joe Pedott who made it a success. Pedott was neither an engineer nor an inventor, but he understood consumer behavior and knew how to advertise. Plus he has a great life story.

Pedott was born in Chicago in 1932 into the Great Depression. At the age of 11, he contracted rheumatic fever and was bedridden for more than a year. His mother died when he was 13 from a cerebral hemorrhage. A few years later, after fighting with his father, he ran away from home and took shelter at the YMCA. It was a rough start to life.

Luckily, counseling and a scholarship helped set him on a better track. He attended the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, majoring in journalism, and got his first job in radio, working on a local children’s show. He also worked as a switchboard operator and sold women’s shoes. While still in college, he and a classmate wrote and produced local commercials, but the partnership broke up a few years after graduation.

In 1958, Pedott moved to San Francisco, where he lived for the rest of his life as an ad man. He did well, and then he did really well, when he discovered the terra-cotta ram that became the first Chia Pet. As with the Clapper, Pedott didn’t invent the Chia Pet, a clay figurine that would sprout a green coat of chia plants. The figurines weren’t turning a profit, but Pedott recognized the potential and bought the rights. Then he examined the supply line, cut out the middleman, wrote a catchy jingle, and turned the Chia Pet into a household name.

The Real Original Chia Pet 1984www.youtube.com

Pedott’s memorable ads for the Chia Pet and the Clapper, as well as the Garden Weasel and the Ove Glove, weren’t high art but they moved product, convincing tens of millions of viewers to buy gizmos they never imagined they needed.

In the process, Pedott became a millionaire and a generous philanthropist, giving back to the charity that first got him on his feet, the Scholarship and Guidance Association, as well as many others. In 2018, Pedott sold Joseph Enterprises to NECA, the National Entertainment Collectibles Association, which continues to distribute the Chia Pet and the Clapper. Pedott died last year at the age of 91.

Pedott lived long enough to see the evolution of home automation. I like to think he was tickled by the fact that his patent for the Clapper has been cited by 113 other patents, including a 2013 patent filed by Apple for “Forming Computer System Networks Based on Acoustic Signals.” It’s not such a long road from clapping to “Siri, can you turn off the lights?”

Part of a continuing serieslooking at historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the January 2024 print issue as “The Sound of Two Hands Clapping.”

References

I was inspired to dig into the history of the Clapper after reading Charles Rice’s essay on it in the book Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects (Reaktion Books, 2021). The essay was also published by Slate.

In writing this column, I traced the evolution of the Clapper through its (very entertaining) patent records. The Clapper wasn’t the first product to attempt to automate home appliances, but it definitely sparked consumers to think more was possible.

In 2003 Joe Pedott donated his business records to the Archives Center at the National Museum of American History. He also recorded his oral history with them, which I consulted. I love this first-person account of how he remembered the invention process. However, there are pitfalls. For example, I could never corroborate some negative statements Pedott made about the Clapper’s original inventors, Liljequist and Chen.

Finally, I learned quite a bit about Pedott’s entrepreneurial spirit and philanthropy through various news stories covering his life, including articles in the Jewish News of Northern California.

Allison Marsh is a professor at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the university's Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society. She combines her interests in engineering, history, and museum objects to write the Past Forward column, which tells the story of technology through historical artifacts.