Cleveland City Planners Change Policies to Create 15-Minute City

Cleveland, Ohio, has approved new zoning and transportation policies that are angling to transform it into the next “fifteen-minute city,” The City Planning Commission voted to move forward with changes to building codes in several pilot neighborhoods it wants to make more pedestrian friendly. However, such policies have become contentious with European examples further down the path of progress seeing relatively consistent opposition due to the fact that the ultimate goal is to eliminate the automobile.

This is actually something Cleveland has been working on for years, starting way back in 2015. However, the program hadn’t built the necessary momentum until the pandemic. In 2022, Mayor Justin Bibb introduced the fifteen-minute premise as a way to modernize the city, citing Paris as the example.

"The basic concept of a fifteen-minute city is this ideal planning framework where human needs and desires are accessible within a fifteen-minute walk, bicycle ride, or transit trip," Matt Moss, a planner with Cleveland City Planning Commission, stated at the time. "That's really what we're striving for in this new planning model."

However, the idea needed to take into account which neighborhoods could even accommodate these changes. Many places in Cleveland are effectively too poor for the concept to work due to there being a deficit of amenities. Bike lanes and green space aren’t going to be appreciated by people living in areas without grocery stores, schools, or places to work. Urban planners had their work cut out for them and officials pivoted to changing zoning laws and incentives for a transit-oriented development that doesn't plan around parking or additional driving lanes.

Fast forward to this week and Cleveland.com is reporting the necessary changes have been made with three neighborhoods being targeted for construction — Hough, Opportunity Corridor and the Detroit Shoreway/Cudell.

From Cleveland.com:

The city views the pilot rezoning as a prelude to wider application across Cleveland, with opportunities to tweak and make adjustments as development unfolds under the new code.

The new zoning is designed to regulate the density and built form of buildings by controlling factors such as height, closer setbacks from streets, and specified amounts of windows to increase ground-level transparency.

The new code would emphasize graphic illustrations of requirements alongside 200 pages of text. It would largely replace, or in some cases work alongside, the existing code, developed in 1929, which largely regulates land use and is expressed primarily through text.

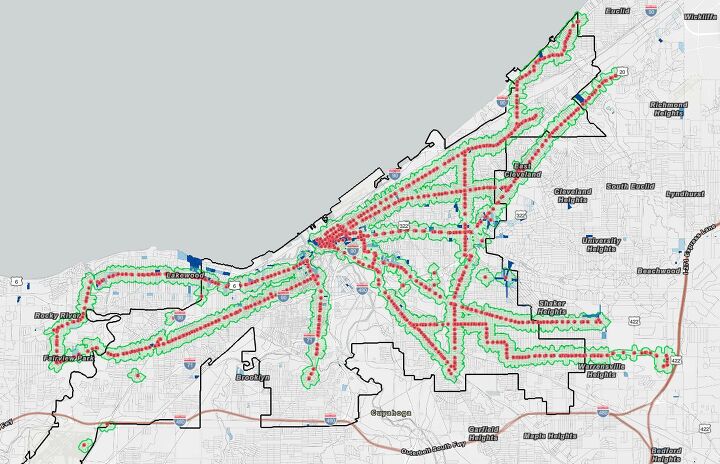

The second vote Friday established new performance standards for a “Transportation Demand Management’' requirements developers would need to meet for projects located in roughly a dozen transit corridors across the city.

Subsidies will also be awarded to businesses (via a points system) based around offering services encouraging public transportation and bicycling. This could be as simple as a company offering employees a transit pass or as complicated as a corporation helping to refurbish bus stations. Minimum parking laws are also being done away with, since the point of the scheme is to reduce automotive traffic as much as possible. The new standards will reportedly come into effect in less than a month.

“I’m excited about these two initiatives and bringing my vision of prioritizing a vision of people over cars,’’ Bibb said. “We’re a transit city, we’re a bike city, and it’s time we started acting like it.’’

Potential benefits aside, this will undoubtedly become a controversial issue as things progress. Fifteen-minute cities are an admirable concept and tend to work in urban areas that were never designed with cars in mind to begin with. But they’re broadly unpopular in places where people have to commute to work, as they’re often accompanied by rather aggressive traffic laws. They’ve also fallen under criticism due to the fact that they’re frequently framed as grass-roots initiatives, when they’re actually the most top-down central planning imaginable.

Vision Zero policies were something I became aware of at the impetus of the automotive industry pushing self-driving vehicles roughly seven years ago. At the time, they were being used as a way to nudge U.S. legislators to re-imagine preexisting vehicle safety standards to better accommodate self-driving vehicles, ensuring they would be placed on public roads as quickly as possible. The assumption here is that connected vehicles could force drivers into changing their behavior, collect valuable data for law enforcement, and eventually remove the human driver from the equation. But this is but a singular component.

Vision Zero is a globally focused United Nations initiative designed to totally eliminate all traffic accidents by implementing comprehensive changes to the legal framework of traffic laws, the expansion of public transportation, and physically changing roadways to accommodate those modifications. While initially quite vague, Vision Zero has grown to incorporate combating assumed environmental harms caused by automobiles, achieving "transportation equity," and has been leveraged by a myriad of governments (particularly in Europe) hoping to reshape urban environments.

While this has resulted in cities pushing for more walkable areas and additional greenspace for pedestrians, we’ve also seen Vision Zero used to rationalize extremely low speed limits, unmitigated data collection, and unparalleled traffic surveillance that’s now baked in with automated traffic enforcement. If you live in a major metropolitan area, and were recently subjected to congestion charging, dramatically lower speed limits, or some kind of automated ticketing mechanism, there’s an extremely good chance those decisions were influenced by Vision Zero policies.

Fifteen-minute cities are effectively an offshoot of Vision Zero and are designed to create sustainable urban environments that mitigate pollution while also being convenient for the local population. Ideally, it’s supposed to create pedestrian-friendly environments where residents can have all their daily needs met without needing to hop into a privately owned automobile. However, the public response could be graciously described as mixed.

Many European cities have seen the implementation of Ultra Low Emission Zones (ULEZ) that fine drivers for using certain roadways without being in the correct type of car. The assumption here is that such decisions would encourage locals to purchase more electric vehicles while also discouraging them from driving when it’s not absolutely necessary. However, some residents of the the United Kingdom and France have taken to destroying surveillance cameras and blocking enforcement vehicles in protest on the basis that they find the scheme oppressive and extremely greedy.

Having reported on the topic frequently, your author was often told that these were European problems that would never migrate here. This continued after New York City adopted lower speed limits, replaced driving lanes with bicycle paths, raised tolls, and eventually introduced congestion charging in Manhattan with the accumulated riches going to the city’s absolutely broken Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Less than a year away from Manhattan being outfitted with congestion cameras and Cleveland is ready to try its hand at becoming a fifteen-minute city. This was always a global initiative focused on changing roads in every Western town and, while I’m certain some good things will come of it, they will happen overwhelmingly at the expense of drivers. The only real questions are how far will it go, how long it will take, what’s truly fair, and whether or not these trade offs will be appreciated by the locals.

[Image: Cleveland Planning Commission]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to the truth about cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

A staunch consumer advocate tracking industry trends and regulation. Before joining TTAC, Matt spent a decade working for marketing and research firms based in NYC. Clients included several of the world’s largest automakers, global tire brands, and aftermarket part suppliers. Dissatisfied with the corporate world and resentful of having to wear suits everyday, he pivoted to writing about cars. Since then, that man has become an ardent supporter of the right-to-repair movement, been interviewed on the auto industry by national radio broadcasts, driven more rental cars than anyone ever should, participated in amateur rallying events, and received the requisite minimum training as sanctioned by the SCCA. Handy with a wrench, Matt grew up surrounded by Detroit auto workers and managed to get a pizza delivery job before he was legally eligible. He later found himself driving box trucks through Manhattan, guaranteeing future sympathy for actual truckers. He continues to conduct research pertaining to the automotive sector as an independent contractor and has since moved back to his native Michigan, closer to where the cars are born. A contrarian, Matt claims to prefer understeer — stating that front and all-wheel drive vehicles cater best to his driving style.

More by Matt Posky

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- W Conrad I'm not afraid of them, but they aren't needed for everyone or everywhere. Long haul and highway driving sure, but in the city, nope.

- Jalop1991 In a manner similar to PHEV being the correct answer, I declare RPVs to be the correct answer here.We're doing it with certain aircraft; why not with cars on the ground, using hardware and tools like Telsa's "FSD" or GM's "SuperCruise" as the base?Take the local Uber driver out of the car, and put him in a professional centralized environment from where he drives me around. The system and the individual car can have awareness as well as gates, but he's responsible for the driving.Put the tech into my car, and let me buy it as needed. I need someone else to drive me home; hit the button and voila, I've hired a driver for the moment. I don't want to drive 11 hours to my vacation spot; hire the remote pilot for that. When I get there, I have my car and he's still at his normal location, piloting cars for other people.The system would allow for driver rest period, like what's required for truckers, so I might end up with multiple people driving me to the coast. I don't care. And they don't have to be physically with me, therefore they can be way cheaper.Charge taxi-type per-mile rates. For long drives, offer per-trip rates. Offer subscriptions, including miles/hours. Whatever.(And for grins, dress the remote pilots all as Johnnie.)Start this out with big rigs. Take the trucker away from the long haul driving, and let him be there for emergencies and the short haul parts of the trip.And in a manner similar to PHEVs being discredited, I fully expect to be razzed for this brilliant idea (not unlike how Alan Kay wasn't recognized until many many years later for his Dynabook vision).

- B-BodyBuick84 Not afraid of AV's as I highly doubt they will ever be %100 viable for our roads. Stop-and-go downtown city or rush hour highway traffic? I can see that, but otherwise there's simply too many variables. Bad weather conditions, faded road lines or markings, reflective surfaces with glare, etc. There's also the issue of cultural norms. About a decade ago there was actually an online test called 'The Morality Machine' one could do online where you were in control of an AV and choose what action to take when a crash was inevitable. I think something like 2.5 million people across the world participated? For example, do you hit and most likely kill the elderly couple strolling across the crosswalk or crash the vehicle into a cement barrier and almost certainly cause the death of the vehicle occupants? What if it's a parent and child? In N. America 98% of people choose to hit the elderly couple and save themselves while in Asia, the exact opposite happened where 98% choose to hit the parent and child. Why? Cultural differences. Asia puts a lot of emphasis on respecting their elderly while N. America has a culture of 'save/ protect the children'. Are these AV's going to respect that culture? Is a VW Jetta or Buick Envision AV going to have different programming depending on whether it's sold in Canada or Taiwan? how's that going to effect legislation and legal battles when a crash inevitibly does happen? These are the true barriers to mass AV adoption, and in the 10 years since that test came out, there has been zero answers or progress on this matter. So no, I'm not afraid of AV's simply because with the exception of a few specific situations, most avenues are going to prove to be a dead-end for automakers.

- Mike Bradley Autonomous cars were developed in Silicon Valley. For new products there, the standard business plan is to put a barely-functioning product on the market right away and wait for the early-adopter customers to find the flaws. That's exactly what's happened. Detroit's plan is pretty much the opposite, but Detroit isn't developing this product. That's why dealers, for instance, haven't been trained in the cars.

- Dartman https://apnews.com/article/artificial-intelligence-fighter-jets-air-force-6a1100c96a73ca9b7f41cbd6a2753fdaAutonomous/Ai is here now. The question is implementation and acceptance.

Comments

Join the conversation

I submitted a comment yesterday that hasn't appeared.

It was in relation to driving through someone's community. These people do have a say in how they expect those travelling through their community need to conform and comply to their wishes. If a community wants to be given priority over those who are transiting through then that's acceptable.

What is occurring in Cleveland has nothing to do with eliminating motor vehicles but how to better manage the use of motor vehicles to give the local population a better life.

As Posky's belief is "I own a motor vehicle and its my god given right to do as I wish" is a selfish approach. But I'd bet if he had an annoying neighbour he would be the first to cry. Posky is what we call a NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) in Australia. He's all for anything so long as he doesn't have to contribute. He can dress up his arguments as "I'm trying to find better approach", in political circles this is called "kicking the can down the road". He must realise that he's in someones domain and if he doesn't like it find another route.

Cleveland had 914,808 residents in 1950. Now it's 351,389, having lost over 563,000 in population. They've gone from 7th largest city in the US to 54th largest. Planters, trees, limiting parking, and bike lanes didn't help rejuvenate the city, and this scheme won't do it either. Ironically, the city probably already had 15 minute neighborhoods, but zoning, permits, and business taxes eliminated the small stores all over the city.