Why Are Modern Vehicles So Much Bigger?

Over the weekend, your author was wandering through a massive parking lot in mixed company and was asked why modern vehicles are so much larger than their predecessors. It’s a frequent question and one that requires an answer that seems counterintuitive on its face.

While consumer preferences have trended toward larger automobiles of late, it’s actually the United States’ regulatory landscape that has been steering us toward gargantuan vehicles. Safety standards have required the implementation of systems that often won’t fit into older/smaller designs and loopholes in the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards have resulted in manufacturers sizing up models to exploit regulatory blind spots.

Before you prep your fingers to type in the comments section about how that doesn’t make any sense, know that you are correct. But that doesn’t mean it hasn’t been taking place over the last few decades. Let’s take a trip back in time to see how this all started.

In the 1960s, Americans were enjoying cheap gasoline and everyday automobiles boasting some of the largest engines ever manufactured. While years before my time, just about every enthusiast who lived through the era regards it as a golden age and there’s a surplus of nostalgia for vehicles manufactured from the period.

This changed in the following decade. The Yom-Kippur War of 1973 and the Iranian Revolution of 1979 resulted in severe oil shortages that primarily impacted the Western world. Production was down, shipping routes were closed, and OPEC nations issued embargoes that ensured the United States would be punished for allying itself with Israel.

In response, the United States mandated that the national speed limit be restricted to 55 mph in a bit to reduce fuel consumption. Meanwhile, Congress prepped the new Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards to force manufacturers to build more efficient vehicles. Enacted in 1975, the rules effectively made it more expensive for automakers to develop less-economical powertrains. They were now required to reach mpg benchmarks or face financial penalties from the government.

The initial response was to continue producing larger automobiles with large motors re-tuned for efficiency, rather than power. But the industry also started to pivot toward smaller vehicles as pint-sized imports began to flood the market. Automobiles became smaller for a time and adapted to meet the changing regulatory standards.

Today’s CAFE standards are supposed to address fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. But the industry has learned it's easier to work around the system and has been designing vehicles intended for the American market around the CAFE standard’s distinction between “passenger vehicles” and “light trucks.”

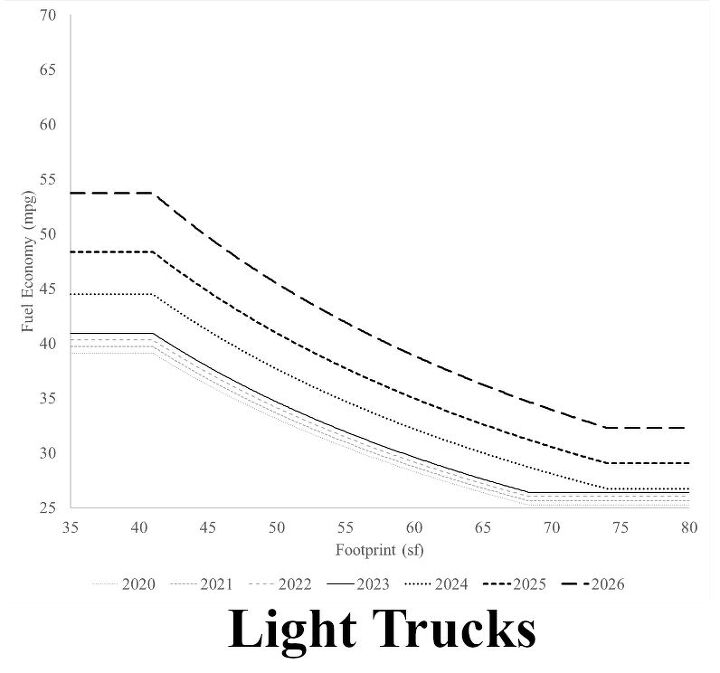

While there are layers upon layers determining how the government decides to classify vehicles, light trucks are defined quite broadly and are not subject to the same fueling standards as passenger vehicles. If you want to know all the details, check out the Federal Code of Regulations. But the gist is that basically anything that has enough space to haul some plywood in the back or has any kind of legitimate off-road capability could theoretically be deemed a light truck.

This explains why the industry seems totally obsessed with selling crossover vehicles, SUVs, and pickup trucks to Americans. It also helps explain why practical fuel economy averages for the nation haven’t improved by all that much since 2015. But there’s more going on here than manufacturers ensuring their products can be classified in a way that ensures they’re not subject to the most stringent fuel economy rules. CAFE also takes into account the footprint of individual models.

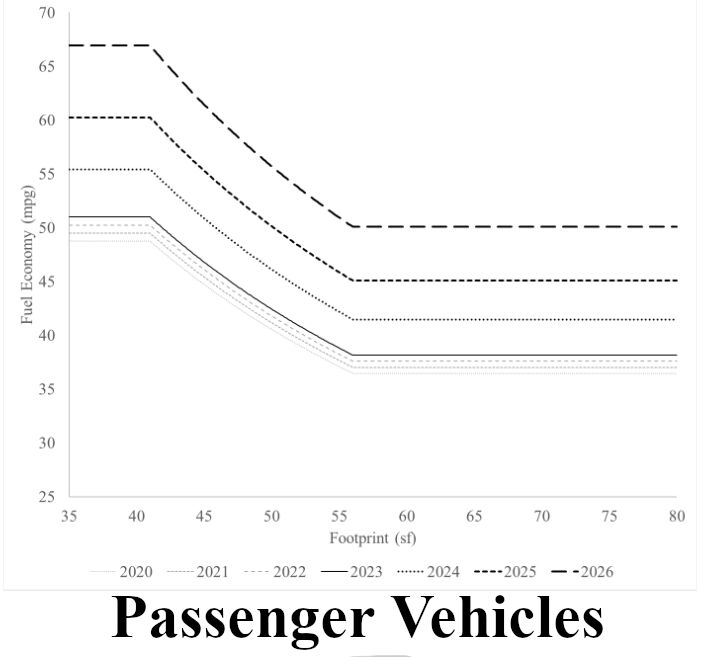

Starting in 2011, the U.S. government revised CAFE standards to incorporate a vehicle’s size based on its wheelbase and track width. Requirements were set up such that a vehicle with a larger footprint has a lower fuel economy requirement than a vehicle with a smaller footprint. This basically spelled the end of traditional economy cars on the market. Domestic brands began culling their smallest models to prioritize crossovers, utility vehicles, and trucks. Imports followed shortly thereafter.

Though the trend was already to build a bigger model. If you track every generation of the Honda Civic, you can see just how massive it has grown over the years. In 1972, the smallest version was 134 inches long by 59 inches wide. By 2023, the littlest Civic is 179 inches long by 71 inches wide. For a time, the Honda Fit (AKA Honda Jazz) filled the gap for an ultra-small economy car. But it, like many vehicles of its size, has been pulled from our market.

Ford’s Ranger is another excellent example. When the vehicle debuted in 1983, it was considered a compact pickup and had plenty of competition. But today’s "midsize" Ranger is closer to the full-size pickups of the past. Even Ford’s Maverick is substantially larger than the original Ranger was and it’s just about the smallest pickup currently available.

While the above may not be common knowledge, it’s hardly a secret. Numerous manufacturers (especially those focused on the production of smaller automobiles) bemoaned the revised regulatory standards. They understood the implications and were not eager to comply with the changes

The media also seemed aware that this could lead to an influx of larger vehicles. In 2011, numerous outlets reported on how the revised CAFE standards would encourage manufacturers to exploit the footprint-based loopholes. Here’s an example from The Washington Post. But there were also studies conducted by the University of Michigan College of Engineering suggesting that vehicles would also get heavier, ultimately leading to an increase in nationwide fuel consumption, as the government had indirectly created a profit incentive for manufacturing bigger automobiles. Annual traffic fatalities were also assumed to increase, as there would be a disparity in old-vs-new vehicle mass.

While larger cars don’t automatically default into being a bad thing, regulatory factors in the United States have resulted in a less diverse automotive market. Some of my favorite vehicles have been massive land yachts. But I also enjoy infinitely practical hatchbacks with a little zip in their step and midsize sport sedans. Unfortunately, many of those models are no longer sold in the United States or have become so specialized that they’re subject to extreme dealer markups.

The up-sizing of vehicles has arguably left MSRPs higher than they otherwise would have been. We’ve also seen roadway fatalities climbing as they’ve gotten heavier as predicted by the University of Michigan College of Engineering study. While there are undoubtedly other factors at play, vehicle sizing is undoubtedly an important factor.

Granted, American consumers have historically preferred larger vehicles than people living elsewhere. This was true in the post-war period and has remained true through the modern era. SUV sales were already supplanting sedan volumes even before CAFE incentivized manufacturers to tweak production trends in the 2010s. There are advantages to owning larger vehicles -- typically improved utility and less noise, vibration, and harshness.

But fuel is notably more expensive these days and disposable incomes are shrinking for a majority of the population as vehicle pricing continues to climb. The bottom may be dropping out for how big vehicles can actually get. Parking spaces have boundaries and we cannot continue widening lanes forever.

However, it’s not clear what could be done. Nixing or changing CAFE regulations might move the needle somewhat, ideally encouraging automakers to compete by building economy cars people might want to buy. But safety regulations will remain in place and they’re the other side of this coin. Even if rules pertaining to crashworthiness were totally eliminated, there’s a good chance consumers would still lean toward larger vehicles. They’ve long been viewed as safer than smaller alternatives and, due to just how many SUVs and pickups are currently on the road today, many drivers elect to purchase one just so they can see over the traffic ahead.

No matter how you slice it, it’s hard to envision a world where the vehicles in North America shrink in size and traditional cars become the norm again. It would likely require extensive regulatory revisions that forced the issue and that’s ultimately what brought us here in the first place. Meanwhile, simply gutting U.S. regulations would, in theory, place the industry in a position to ensure vehicles were safe, efficient, and affordable. While industry competition may eventually result in that happening, most companies aren't in the habit of doing the right thing without pressure coming top-down from regulators or bottom-up from consumers.

[Images: Ram, Honda]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to the truth about cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

A staunch consumer advocate tracking industry trends and regulation. Before joining TTAC, Matt spent a decade working for marketing and research firms based in NYC. Clients included several of the world’s largest automakers, global tire brands, and aftermarket part suppliers. Dissatisfied with the corporate world and resentful of having to wear suits everyday, he pivoted to writing about cars. Since then, that man has become an ardent supporter of the right-to-repair movement, been interviewed on the auto industry by national radio broadcasts, driven more rental cars than anyone ever should, participated in amateur rallying events, and received the requisite minimum training as sanctioned by the SCCA. Handy with a wrench, Matt grew up surrounded by Detroit auto workers and managed to get a pizza delivery job before he was legally eligible. He later found himself driving box trucks through Manhattan, guaranteeing future sympathy for actual truckers. He continues to conduct research pertaining to the automotive sector as an independent contractor and has since moved back to his native Michigan, closer to where the cars are born. A contrarian, Matt claims to prefer understeer — stating that front and all-wheel drive vehicles cater best to his driving style.

More by Matt Posky

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Steve S. Steve was a car guy. In his younger years he owned a couple of European cars that drained his bank account but looked great and were fun to drive while doing it. This was not a problem when he was working at a good paying job at an aerospace company that supplied the likes of Boeing and Lockheed-Martin, but after he was laid off he had to work a number of crummy temp jobs in order to keep paying the rent, and after his high-mileage BMW was totaled in an accident, he took the insurance payout and decided to get something a little less high maintenance. But what to get? A Volkswagen? Maybe a Volvo? No, he knew that the parts for those were just as expensive and they had the same reputation for spending a lot of time in the shop as any other European make. Steve was sick and tired of driving down that road."Just give me four wheels and a seat," said Steve to himself. "I'll buy something cooler later when my work situation improves".His insurance company was about to stop paying for the rental car he was driving, so he had to make a decision in a hurry. He was not really a fan of domestics but he knew that they were generally reliable and were cheap to fix when they did break, so he decided to go to the nearest dealership and throw a dart at something.On the lot was a two year old Pontiac Sunfire. It had 38,000 miles on it and was clean inside and out. It looked reasonably sporty, and Steve knew that GM had been producing the J-car for so long that they pretty much worked the bugs out of it. After taking a test drive and deciding that the Ecotec engine made adequate power he made a deal. The insurance check paid for about half of it, and he financed the rest at a decent rate which he paid off within a year.Steve's luck took a turn for the better when he was offered a job working for the federal government. It had been months since he went on the government jobs website and threw darts at job listings, so he was surprised at the offer. It was far from his dream job, and it didn't pay a lot, but it was stable and had good benefits. It was the "four wheels and a seat" of jobs. "I can do this temporarily while I find a better job", he told himself.But the year 2007 saw the worst economic crash since the Great Depression. Millions of people were losing their jobs, the housing market was in a free fall, people were declaring bankruptcy left and right, and the temporary job began to look more and more permanent. Steve didn't like his job, and he hated his supervisors, but he considered himself lucky that he was working when so many people were not. And the federal government didn't lay people off.So he settled in for the long haul. That meant keeping the Sunfire. He didn't enjoy it, but he didn't hate it either, and it did everything he asked of it without complaint.Eventually he found a way to tolerate his job too, and he built seniority while paying off his debts. There was a certain feeling of comfort and satisfaction of being debt-free, and he even began to build some savings, which was increasingly important for someone now in their forties.Another bit of luck came a few years later when Steve's landlord decided to sell the house Steve was renting, at the bottom of the housing market, and offered it to Steve for what he had in it. Steve's house was small and cramped, and he didn't really like it, but thanks to his savings and good credit he became a homeowner in an up and coming neighborhood.Fourteen years later Steve was still working that temporary job, still living in that cramped little house that he now hated, and still drove the Sunfire because it wouldn't die. For years now he dreamed of making a change, but then the pandemic happened and threw the economy and life in general into chaos. Steve weathered the pandemic, kept his job when millions of people were losing theirs, and sheltered in place in that crummy little house, with Netflix, HBO, and a dozen other streaming services keeping him company, and drove to and from work in the Sunfire because it was four wheels and a seat and that's all he needed for now.Steve's life was secure, but a kind of dullness had set in. He existed, but the fire went out; even when the pandemic ended and life returned to normal Steve's life went on as it had for years; an endless Groundhog Day of work, home, work, home. He never got his real-estate license or finished college and got his bachelor's, never got a better job, never used his passport to do some traveling in Europe. He lost interest in cars. "To think how much money I wasted on hot cars when I was younger", he said to himself. He never married and lost interest in dating. "No woman would want me anyway. I've gotten so dull and uninteresting that I even bore myself".Eventually the Sunfire began to give trouble. With 200,000 miles on the clock it was leaking oil, developing electrical gremlins, and wallow around on blown-out shocks. Steve wasn't hurting for money and thought about treating himself to a new car. "A BMW 3-series, maybe. Or maybe an Alfa Romeo Giulia!" He began to peruse the listings on Autotrader. "Maybe this is just what I need to pull out of this funk. Put a little fun back in my life. Yeah, and maybe go back to the gym, and who knows, start dating again and do some traveling while I'm still young enough to enjoy it!"Then his father passed away and left him a low-mileage Ford. Steve didn't like it or hate it, but it was four wheels and a seat, and that's all he needed right now."Is it too late to have a mid-life crisis?" Steve thought to himself. For what he needed more than that stable job, that house with an enviably small mortgage payment, and that reliable car was a good kick in the hindquarters. "What the hell am I afraid of? I should be afraid that things will never change!"But the depression was like a drug, a numbness that they call "dysthymia"; where you're neither here or there, alive or dead, happy or sad. It was a persistent overcast, a low ceiling that kept him grounded. The Sunfire sat in his driveway getting buried by the needles from his neighbor's overhanging pine trees which were planted right on the property line. "Those f---ing pine trees! That's another thing I hate about this damn house!" Eventually the Sunfire wouldn't start. "I don't blame you", he said to the car as he trudged past it to drive the Ford to another Groundhog Day at that miserable job.

- Yuda Cool. Cept we need oil and such products. Not just for fuel but other stuff as well. The world isn't exactly ready to move to wind and solar and whatever other bs, the technology simply isn't here yetNot to mention it's too friggin expensive, the equipment is still too niche and expensive as it stands

- Rna65689660 Picked up my wife’s 2024 Bronco Sport Bad Lands!

- Inside Looking Out Android too.

- Ajla I'm replacing the transmission in a 2006 GMC van.

Comments

Join the conversation

Not forcing ICE's, in spite of all the drawbacks, forcing BEV's on consumers with lies of zero emissions. Talk to anyone at a power company, in the know, about additional transformers needed to every street to recharge BEV at home.

Not the quantity of charges, it's the amps needed to charge. The current electrical grid will need a massive upgrade to support a 20/80 ratio BEV to ICE. Additionally, most power companies rely on fossil fuels to generate power. All the useable waterways are dammed and no Nuclear plants since TMI. BEVs will have a place in the automotive landscape, just not a dominant role if environmentalism is a primary concern.