Greta Bekerytė started out cleaning offices and ended up designing electronics for EV charging stations. It’s amazing what you can accomplish in your career when you follow your dreams.

It wasn’t easy. Bekerytė moved from her native Lithuania to Norway in 2010 to take advantage of the country’s free university tuition, but first she had to find a way to support herself. She took the cleaning job, and scrimped and saved to pay for Norwegian reading and writing classes, a requirement to attend a university. It took her four years, but she was finally able to afford the tuition for the language courses, which cost thousands of U.S. dollars.

Greta Bekerytė

Employer:

Zaptec, in Stavanger, Norway

Title:

Hardware engineer

Education:

Bachelor’s degree in industrial automation and circuit design; master’s degree in robotics and signal processing, both from the University of Stavanger, in Norway

She went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in industrial automation and circuit design, followed by a master’s in robotics and signal processing, both from Norway’s University of Stavanger.

Today she works as a hardware engineer at Zaptec, which makes electric-vehicle charging stations and is also based in Stavanger. For her contributions to the field, in 2022 she was selected as one of the Top Women in EV by the organizers of the EV Summit, a leading global e-mobility event.

Bekerytė credits her success to following her heart. “Do what you love,” she says. “Then you will be able to go through all the challenges that come up, and you will have the dedication and drive to actually become what you want to become.”

A specialist at heart

Growing up in Šiauliai, Lithuania, Bekerytė seemed destined to become an engineer. She recalls that when she was about 5 years old, a friend of her mother’s, who worked as an electrical engineer at a company that built power transformers, handed her some old schematics from her job to use as drawing paper.

Bekerytė recalls being impressed that someone could understand those strange symbols. Instead of drawing, she pretended she was working at an office as an engineer who understood the schematics.

“I remember thinking, ‘Wow, are there really people who understand what this is?’” she says. “So I was interested in that kind of thing quite early.”

Bekerytė’s father, who worked in construction and also fixed cars, was another major influence. He was a DIY enthusiast willing to try his hand at just about anything, from electronics to plumbing. She was always curious about his projects and remembers him teaching her to solder at the tender age of 7.

While Bekerytė excelled in math and science, she also was interested in music and art. By the time she graduated high school, she had mapped out three potential career paths: an orchestra conductor, an architect, or an engineer. All she knew for certain was that she wanted to excel in whatever she pursued.

“I always knew I wanted to be a specialist: a person that others would go to because they knew something really well,” she says.

That would turn out to be more challenging than expected.

A brave move

Bekerytė graduated from high school in 2010, the same year Lithuania drastically increased its tuition for state universities. Not wanting to financially burden her parents, Bekerytė decided to relocate with her boyfriend to Norway, where they’d pursue degrees and find work. That path, however, was tougher than they anticipated.

Higher education is free in Norway, but the global job market in 2010 was still in the doldrums following the 2008 financial crisis. Despite diligently looking for jobs for six months, they had no success and decided to move back to Lithuania.

“Don’t listen to others, just listen to yourself. Find that thing that you are really interested in and go for it.”

“We didn’t have any money for rent or food,” Bekerytė recalls. “We decided that on Saturday we would buy ferry tickets, but on Friday I got called for a job interview.”

She was hired to clean offices, and her boyfriend found a job washing the inside of oil tankers. Since both jobs were sporadic, it took four years to save enough money to pay for the language classes.

Making an impression at an engineering contest

After completing the one-year language course at the University of Stavanger in 2016, Bekerytė enrolled in the school’s bachelor’s degree program in industrial automation and circuit design.

The course was demanding, particularly since she was still working part time. Out of 48 students who began the program, only 10 completed it. She decided to continue on at the university and pursue a master’s degree in robotics and signal processing.

Toward the end of her studies in 2019, she got her big break. She applied for an engineering competition run by the Norwegian global power engineering firm Aker Solutions, also in Stavanger. Bekerytė’s team was tasked with improving the operations at an oil-rig construction plant using Internet of Things devices. Her team didn’t win, but the company was so impressed with her that it offered her a job as a safety automation systems engineer. The job involved designing signaling systems on subsea oil wells. She started two weeks after graduating.

The skills hardware engineers need

In 2021 she was contacted by Zaptec for the position of a hardware engineer who would help design its electric-vehicle charging stations. She accepted the offer.

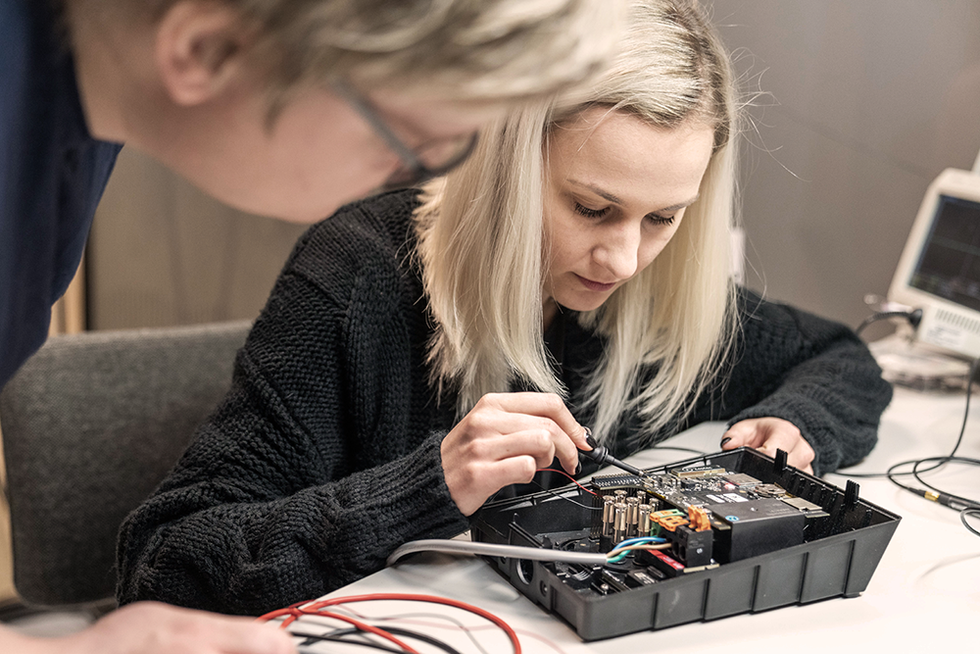

Few companies have roles involving hands-on hardware development, she says, something she loved doing in school. The job entails building devices in the lab and running testing and verification programs.

“It is my dream job,” she says.

A hardware engineer requires a deep understanding of electronics and strong mathematical skills, plus knowledge of computer architecture and low-level programming, she says.

Another, often underappreciated aspect of the job, is having good communication skills, Bekerytė says. “You frequently have to interface with nontechnical teams like marketing,” she explains. “That means you need to be able to explain technical details in ways that nonexperts can understand.”

Breaking through the EV glass ceiling

Although she’s still learning, being named one of the top women in EV has given Bekerytė industry-wide recognition for her work.

The award came as a surprise, Bekerytė says, because she was nominated by a colleague without her knowledge. But she was flattered and glad to find that there was an award recognizing women in a male-dominated field.

She says her colleagues jokingly call her a unicorn because women working in the EV industry are so rare. She thinks providing visibility to women is important to overcome stereotypes about who can and should work in the field.

For the most part, she says she’s faced few barriers because of her gender. But there have been times when she has felt she had to fight to gain the respect of others.

“Sometimes I’ve felt that I need to prove myself a little bit more than others do,” she says.

But if you do what you love, Bekerytė says, all barriers are surmountable. She admits her journey to becoming an engineer was tough, and the only thing that got her through was her deep curiosity for the subject.

“Don’t listen to others, just listen to yourself,” she says. “Find that thing that you are really interested in and go for it.”

Edd Gent is a freelance science and technology writer based in Bengaluru, India. His writing focuses on emerging technologies across computing, engineering, energy and bioscience. He's on Twitter at @EddytheGent and email at edd dot gent at outlook dot com. His PGP fingerprint is ABB8 6BB3 3E69 C4A7 EC91 611B 5C12 193D 5DFC C01B. His public key is here. DM for Signal info.