Watching movies and TV series that use digital visual effects to create fantastical worlds lets people escape reality for a few hours. Thanks to advancements in computer-generated technology used to produce films and shows, those worlds are highly realistic. In many cases, it can be difficult to tell what’s real and what isn’t.

The groundbreaking tools that make it easier for computers to produce realistic images, introduced as RenderMan by Pixar in 1988, came after years of development by computer scientists Robert L. Cook, Loren Carpenter, Tom Porter, and Patrick M. Hanrahan. RenderMan, a project launched by computer graphics pioneer Edwin Catmull, is behind much of today’s computer-generated imagery and animation, including in the recent fan favorites Avatar: The Way of Water, The Mandalorian, and Nimona.

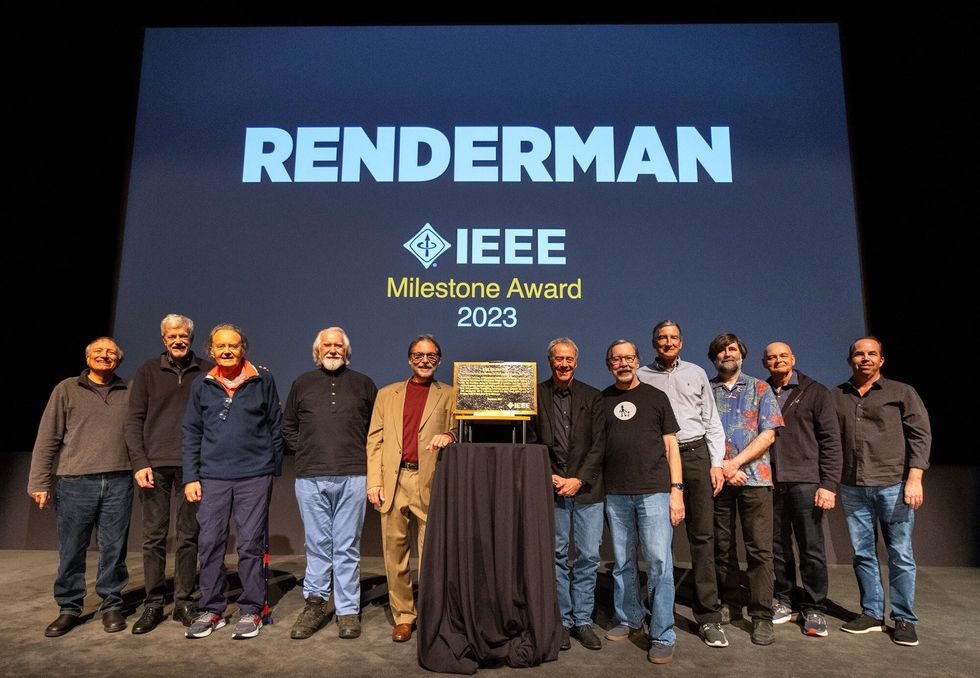

The technology was honored with an IEEE Milestone in December during a ceremony held at Pixar’s Emeryville, Calif., headquarters. The ceremony is available to watch on demand.

“I feel deeply honored that IEEE recognizes this achievement with a Milestone award,” Catmull, a Pixar founder, said at the ceremony. “Everyone’s dedication and hard work [while developing the technology] brought us to this moment.”

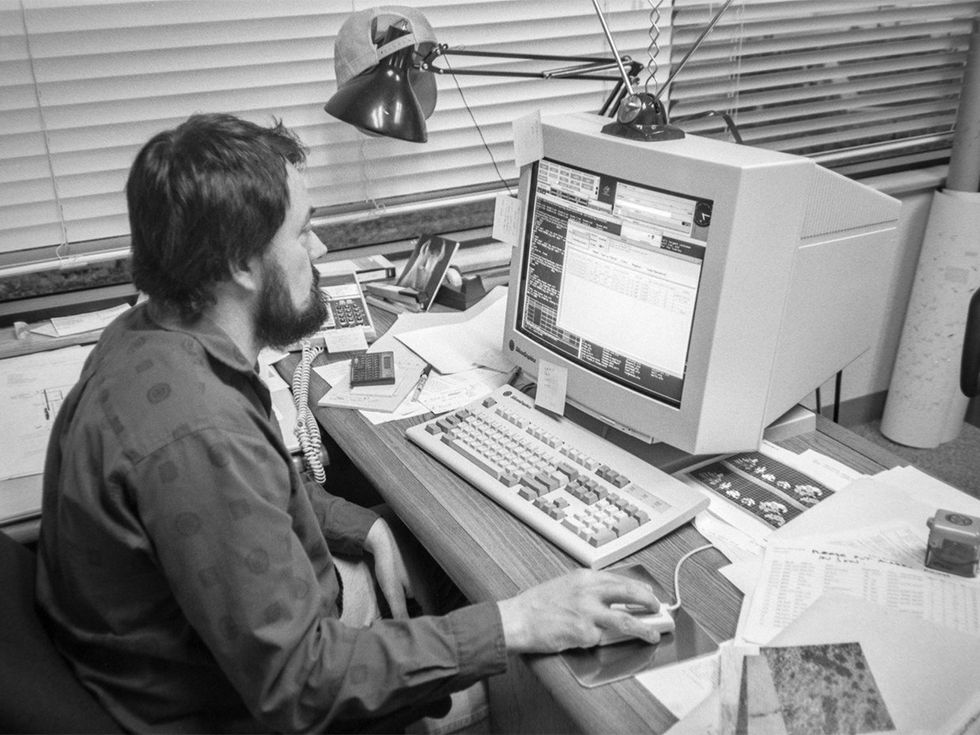

Cook, Carpenter, and Porter collaborated as part of Lucasfilm’s computer graphics research group, an entity that later became Pixar. Hanrahan joined Pixar after its launch. The development of the software that would eventually become RenderMan started long before.

From Utah and NYIT to Lucasfilm

As a doctoral student studying computer science at the University of Utah, in Salt Lake City, Catmull developed the principle of texture mapping, a method for adding complexity to a computer-generated surface. It later was incorporated into RenderMan.

After graduation, Catmull joined the New York Institute of Technology on Long Island as director of its recently launched computer graphics research program. NYIT’s founder, Alexander Schure, started the program with the goal of using computers to create animated movies. Malcolm Blanchard, Alvy Ray Smith, and David DiFrancesco soon joined the lab.

While at the University of Utah, Blanchard designed and built hardware that clipped 3D shapes to only what was potentially visible. Before joining NYIT, Smith, an IEEE life member, helped develop SuperPaint at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in California. It was one of the first computer raster graphics editor programs. DiFrancesco, an artist and scientist, worked with Smith on the project.

“I feel deeply honored that IEEE recognizes this achievement with a Milestone award.” —Edwin Catmull

During the next five years the team created so many pioneering rendering technologies that when Catmull tried to list all its achievements years later, he opted to stop at four pages, according to an article on the history of Pixar.

The team’s technologies include Tween, software that enables a computer to automatically generate the intermediate frames between key frames of action; and the Alpha Channel, which combines separate elements into one image.

“We didn’t keep [our work] secret,” Catmull said in an interview with The Institute. The team created a 22-minute short using its technology. It soon caught the attention of Hollywood producer George Lucas, founder of Lucasfilm and originator of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises.

Lucas, aiming to digitize the film production process, recruited Catmull in 1979 to head the company’s newly created computer division. He tasked the group with developing a digital, nonlinear film editing system, a digital sound editing system, and a laser film printer.

During the next year, Catmull brought Smith, DiFrancesco, and Blanchard to join him.

But Smith, who became director of the division’s graphics group, soon realized that Lucas didn’t fully understand what computer graphics could do for the film industry, he told The Institute in 2018. To show Lucas what was possible, the team decided to develop a rendering program that could create complex, photorealistic imagery virtually indistinguishable from filmed live action images.

They started a rendering team to develop the program. In 1981 Carpenter and Cook came on board. Carpenter had been working in the computer-aided design group at Boeing, in Seattle, where he developed procedural modeling. The algorithm creates 3D models and textures from sets of rules.

Cook, then a recent graduate of Cornell, had published a paper on why nearly every computer-generated object had a plasticlike appearance. His article found its way to Catmull and Smith, who were impressed with his research and offered Cook a job as a software engineer.

And then the project that was to become RenderMan was born.

From REYES to RenderMan

The program was not always known as RenderMan. It originally was named REYES (render everything you ever saw).

Carpenter and Cook wanted REYES to create scenery that mimicked real life, add motion blur, and eliminate “jaggies,” the saw-toothed curved or diagonal lines displayed on low-resolution monitors.

No desktop computer at the time was fast enough to process the algorithms being developed. Carpenter and Cook realized they eventually would have to build their own computer. But they first would have to overcome two obstacles, Cook explained at the Milestone ceremony.

“Computers like having a single type of object, but scenes require many different types of objects,” he said. Also, he added, computers “like operating on groups of objects together, but rendering has two different natural groupings that conflict.”

Those are shading (which you do on every point on the same surface) and hiding (the things you do at every individual pixel).

Carpenter created the REYES algorithm to resolve the two issues. He defined a standard object and called it a micropolygon, a tiny, single-color quadrilateral less than half a pixel wide. He figured about 80 million micropolygons were needed per the 1,000 polygons that typically made up an object. Then he split the rendering into two steps: one to calculate the colors of the micropolygons and the other to use them to determine the pixel colors.

To eliminate jaggies, Cook devised the so-called Monte Carlo technique. It randomly picks points—which eliminates jaggies and the interference of light. Noise patterns appeared, however.

“But there is another way you can pick points,” Cook explains. “You pick a point randomly, and the next point randomly, but you throw the next one out if it is too close to the first point.”

Problems RenderMan Had to Solve

Computer scientists Robert L. Cook and Loren Carpenter took on the initial challenge of developing the computer graphics software that became Renderman. They created this list of tasks for the tool:

- Create complex scenes, with several different computer-generated objects in a scene to mimic real life.

- Give texture to wooden, metallic, or liquid objects. (At the time, computer-generated objects had a plasticlike appearance.)

- Eliminate jaggies, the saw-toothed appearance of curved or diagonal lines when viewed on a low-resolution monitor. They appear at an object’s edges, mirror reflection, and the bending of light rays when they pass through transparent substances such as glass or water.

- Create motion blur or the apparent streaking of moving objects caused by rapid movement.

- Simulate the depth-of-field effect, in which objects within some range of distances in a scene appear in focus, and objects nearer or farther than this range appear out of focus.

- Generate shadows only in the direction of the light source.

- Create reflections and refractions on shiny surfaces.

- Control how deep light penetrates the surface of an object.

That is known as a Poisson disk distribution, modeled on the distribution of cells in the human retina—which also have a seemingly random pattern but with a consistent minimum spacing.

The Monte Carlo change eliminated the annoying visual effects. The distribution also simplified several other tasks handled by the rendering software, including the creation of motion blur and a simulated depth-of-field effect.

“Creating motion blur was probably the single hardest problem we had,” Catmull told IEEE Spectrum in a 2001 interview. Porter, who was part of the graphics group, came up with a way to use the random sampling notion to solve motion blur. In addition to determining what colors appear at each point, the computer considers how that changes over time. Using point sampling, Cook explained, the group found a simple solution: “To every one of your random samples, you assign a random time between when a traditional camera’s shutter would open and when that shutter would close.” Averaging the times creates a blurred image.

The same process worked to simulate the depth-of-field effect: an image in which some areas are in focus and some are not. To create the lack of focus using point sampling, the software assigns a random spot on an imaginary lens to each randomly selected point.

They initially tried the software on a VAX 11/780 computer, running at 1 million instructions per second. But it was too slow, so the team developed the Pixar image computer. It executed instructions at a rate of 40 MIPS, making it 200 times faster than the VAX 11/780, according to the Rhode Island Computer Museum.

Pixar was funded thanks to Steve Jobs

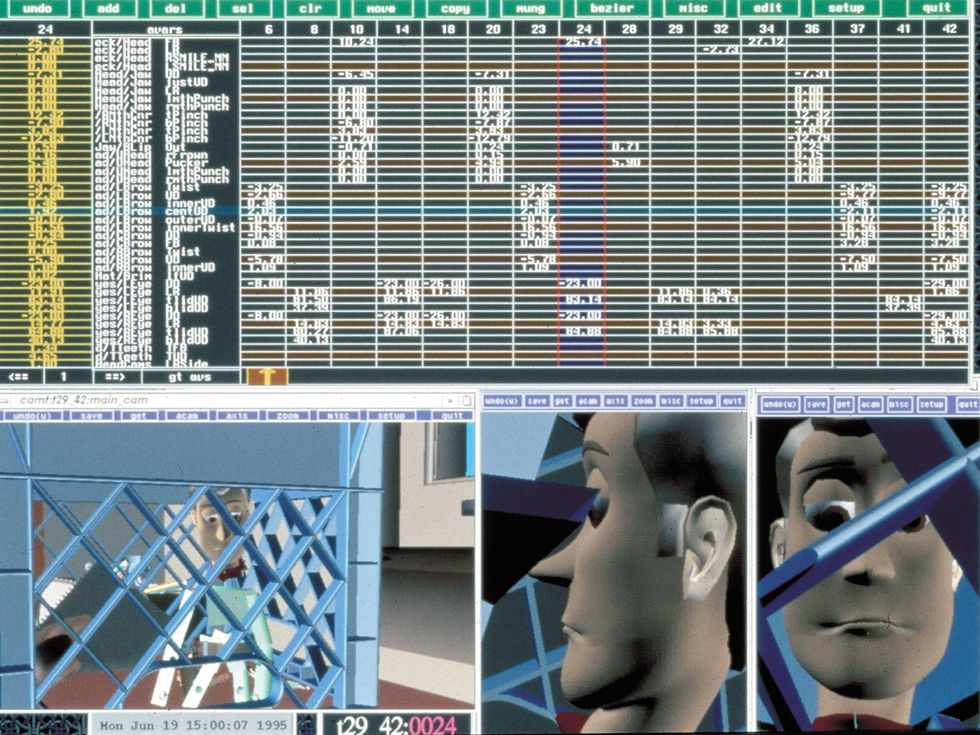

In 1984 the graphics group invited animator John Lasseter to direct the first short film using REYES. The Adventures of André & Wally B. featured a boy who wakes in a forest after being annoyed by a pesky bumblebee. The movie premiered at the Association for Computing Machinery’s 1984 Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques conference.

After the premiere, visual effects studio Industrial Light and Magic asked the team to create the first CGI-animated character to be used in a live-action feature-length film. The group developed the stained-glass knight character for the 1985 Young Sherlock Holmes movie.

In 1986 the Lucasfilm graphics group, now with 40 employees, was spun out into a separate company that went on to become Pixar.

“At first it was a hardware company,” Smith says. “We turned a prototype of the Pixar image computer into a product. Then we met with some 35 venture capitalists and 10 companies to see if they would fund Pixar. Finally, Steve Jobs signed on as our majority shareholder.”

REYES contained a custom-built interface that had been written to work with software used by Lucasfilm, so the teams needed to replace it with a more open interface that would work with any program sending it a scene description, according to the Milestone entry on the Engineering and Technology History Wiki.

In 1988, with the help of computer graphics pioneer Hanrahan, Pixar scientists designed a new interface. Hanrahan helped refine shading language concepts as well. Thanks to a conversation that Hanrahan had about futuristic rendering software being so small it could fit inside a pocket, like a Sony Walkman, REYES became RenderMan. Pixar released the tool in 1988.

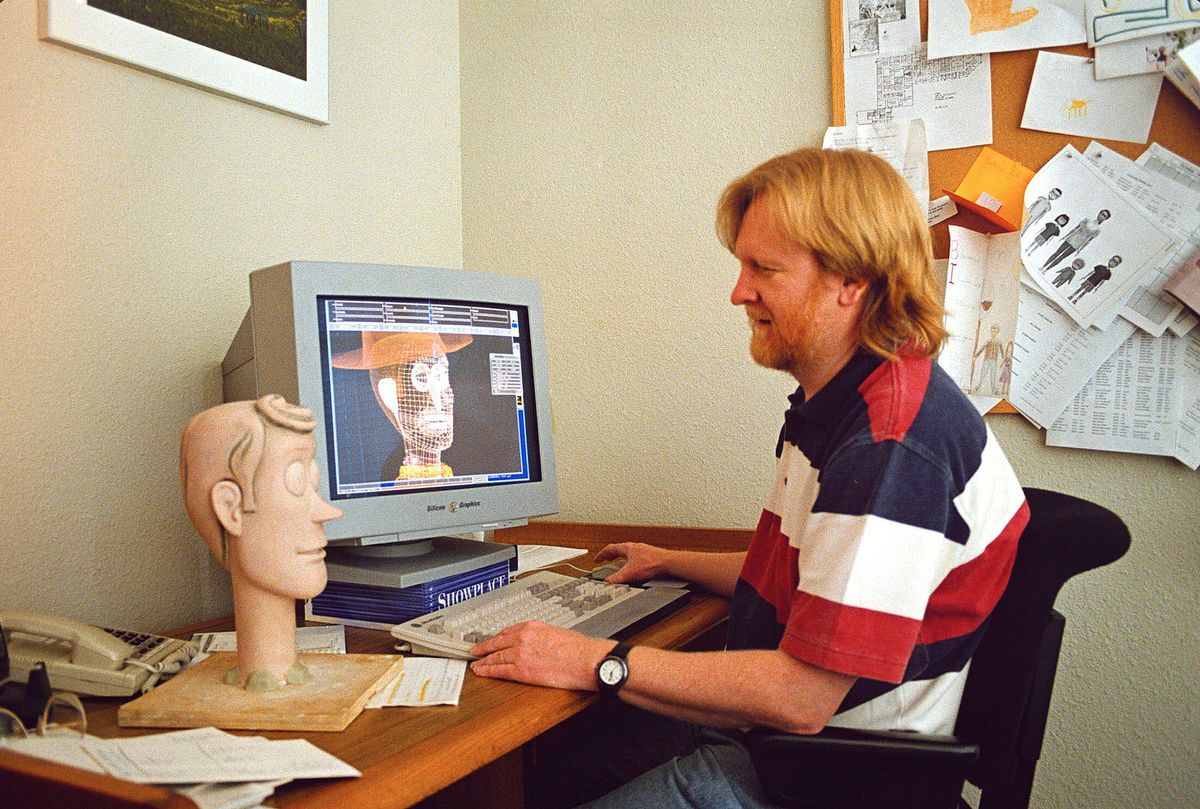

Three years later, Pixar and Walt Disney Studios partnered to “make and distribute at least one computer-generated animated movie,” according to Pixar’s website. The first film was Toy Story, released in 1995. The first fully computer-generated animated movie, it became a blockbuster.

RenderMan is still the standard rendering tool used in the film industry. As of 2022, the program had been used in more than 500 movies. The films it helped create have received 15 Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature and 26 for Best Visual Effects.

In 2019 Catmull and Hanrahan received the Turing Award from the Association for Computing Machinery for “fundamental contributions to 3-D computer graphics and the revolutionary impact of these techniques on computer-generated imagery in filmmaking and other applications.”

A plaque recognizing the technology is displayed next to the entrance gates at Pixar’s campus. It reads:

RenderMan software revolutionized photorealistic rendering, significantly advancing the creation of 3D computer animation and visual effects. Starting in 1981, key inventions during its development at Lucasfilm and Pixar included shading languages, stochastic antialiasing, and simulation of motion blur, depth of field, and penumbras. RenderMan’s broad film industry adoption following its 1988 introduction led to numerous Oscars for Best Visual Effects and an Academy Award of Merit for its developers.

Administered by the IEEE History Center and supported by donors, the Milestone program recognizes outstanding technical developments around the world.

The IEEE Oakland–East Bay Section in California sponsored the nomination, which was initiated by IEEE Senior Member Brian Berg, vice chair of IEEE’s history committee.

“It’s important for this history to be documented,” Smith told The Institute, “and I see that as one of the roles of IEEE: recording the history of its own field.

“Engineers and IEEE members often don’t look at how technological innovations affect the people who were part of the development. I think the [Milestone] dedication ceremonies are special because they help highlight not just the tech but the people surrounding the tech.”

Joanna Goodrich is the associate editor of The Institute, covering the work and accomplishments of IEEE members and IEEE and technology-related events. She has a master's degree in health communications from Rutgers University, in New Brunswick, N.J.