Can Neural Stimulation Zap Addiction?

Different types of brain stimulation may reduce cravings

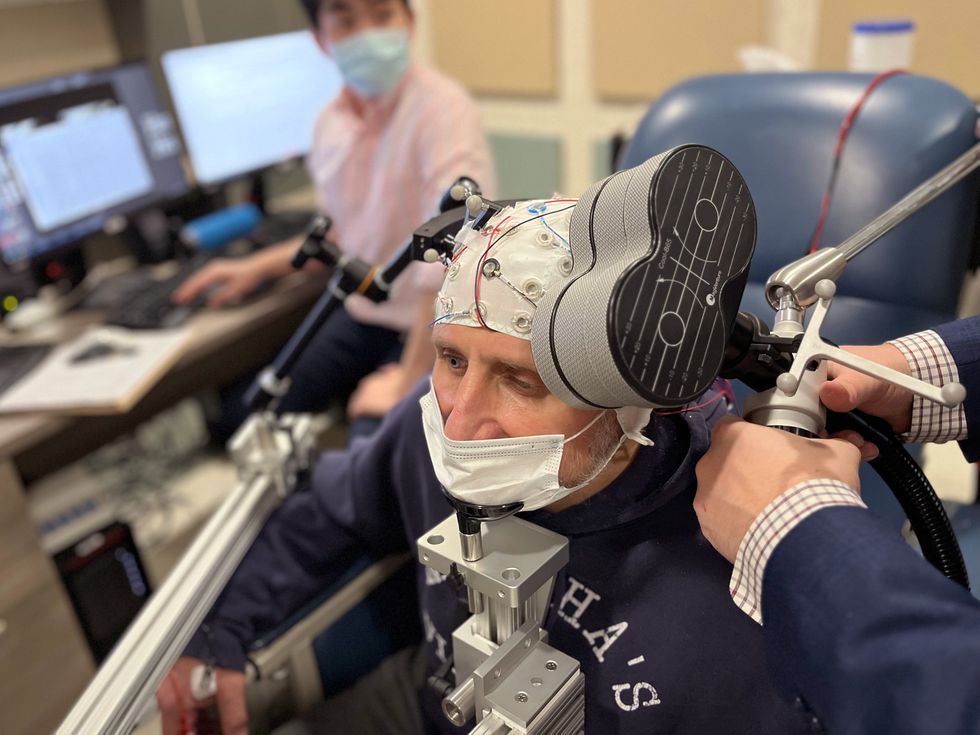

On a rainy Thursday afternoon earlier this year, a neuroscientist named Vaughn Steele placed a figure-eight-shaped wand over a man’s scalp and began jolting him with powerful magnetic pulses. “We’ll start low and ramp up,” said Steele, an addiction researcher at Yale School of Medicine. The patient’s left eyebrow twitched with each zap as he stared at images of pill bottles, syringes, and other drug paraphernalia.

The patient, whom we’ll call Peter B. to protect his privacy, first tried heroin at a New Year’s party in the mid-1990s. He quickly moved from snorting to injecting the drug, and within a year, he was a daily user. Despite four overdoses, five residential detox programs, and a couple of stints in jail, he’s still struggling with addiction nearly three decades later.

Now in his mid-50s and in treatment with methadone, Peter continues to inject a synthetic opioid drug called fentanyl several times per week—“just to prevent getting sick,” he said. Without the drugs, he gets achy. Hot flashes, sweats, and shivers overtake him. “It’s just miserable,” he said.

Peter, a former construction worker from East Hartford, Conn., wishes things were different. “But I’ll be honest with you,” he said, “it’s a strong addiction.” And with his neural circuitry now reliant on drugs, getting sober seems like a near impossibility—unless Steele can rewire his brain with electromagnetism.

The device that Steele deployed used magnetic pulses to generate an electric field in Peter’s prefrontal cortex, the brain’s center for rational thinking and decision-making. Within the cortex, nerve cells fired like charged storm clouds, which set off waves of electrical activity that cascaded through Peter’s brain. As the process repeated, it strengthened connections between the cells and enhanced neural communication, much as weight training helps to fortify muscles and improve physical performance.

During the magnetic-stimulation treatment, Peter was shown pictures of drugs and encouraged to reflect on the harmful consequences of his addiction. The hope is that his brain’s reward circuits—a complex network of interwoven brain regions that control pleasure-seeking behaviors—will get reconfigured in ways that ultimately alleviate cravings and strengthen self-control.

But, as Steele points out, much remains to be learned about the treatment’s brain-changing effects and how to maximize its therapeutic impact. Different research groups have different theories, for example, about whether brain-modulation techniques should be paired with other types of mental health treatments, whether existing stimulator technology is sufficiently attuned to the task, and even about which brain regions to target.

“We’re not completely in the dark,” Steele told IEEE Spectrum, “but we have a long way to go before this can be rolled out as a widespread treatment for addiction.”

TMS: An Up-and-Coming Treatment for Addiction

This type of brain-zapping therapy, known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), has shown encouraging results in clinical trials involving chronic users of cocaine, alcohol, heroin, methamphetamine, and cannabis. Regulators in the United States, Canada, the European Union, and Israel have already authorized the treatment as an aid for cigarette smokers hoping to kick the habit.

But most studies of TMS for addiction have been small and short, relying on brain-stimulation parameters borrowed from the treatment playbook for other psychiatric conditions. Generally, those parameters involve pulses at a frequency of 5 to 20 hertz—a few seconds on, longer pauses off, repeated many times in daily sessions lasting up to 30 minutes. They’re rarely optimized to specifically address substance-use disorders.

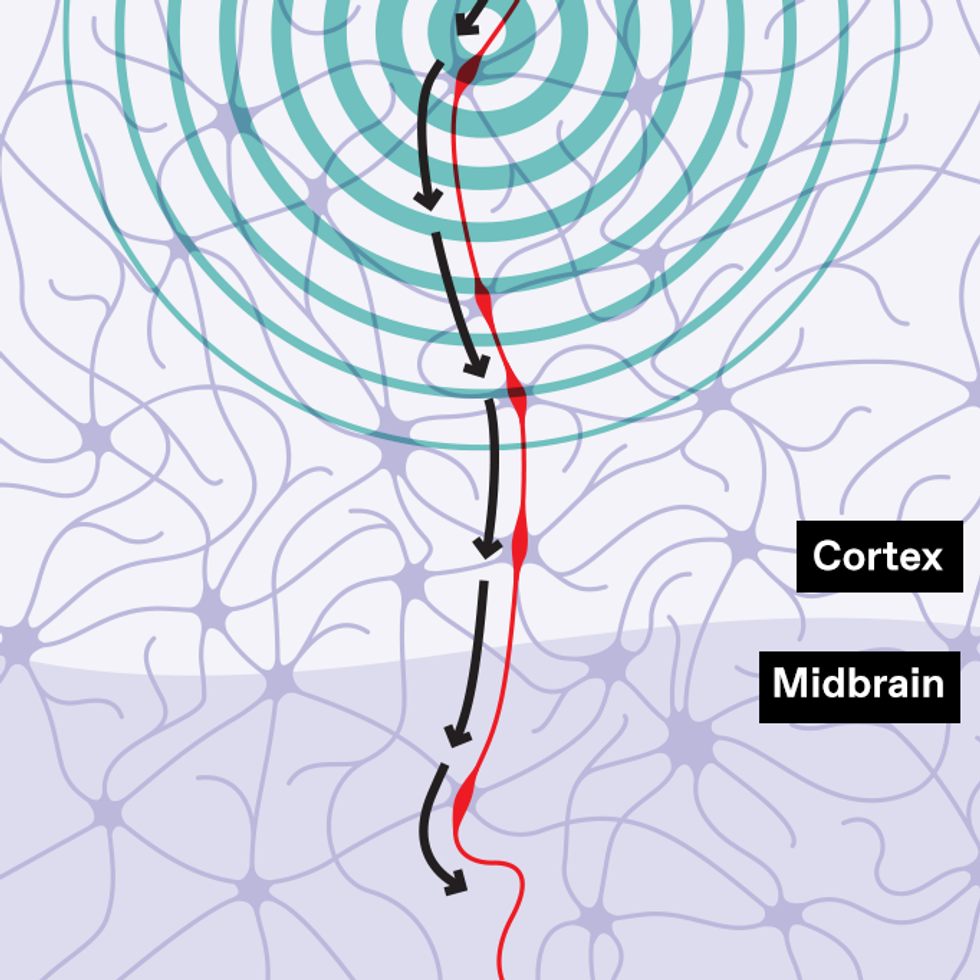

With transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a magnetic field induces an electric current that alters the activity of brain cells, which are connected in neural circuits. Stimulation can increase or decrease activity in a circuit. Both tactics can be useful in fighting addiction.

Chris Philpot

Steele sees room for improvement. That’s why he and others continue to perform controlled research studies, under laboratory settings, in which they administer TMS alongside brain scans or other tests of brain activity.

They hope to refine the approach ahead of mainstream adoption. Steele, for one, sees promise in a form of TMS known as intermittent theta-burst stimulation, which involves delivering a rat-a-tat stream of high-frequency magnetic pulses over just a few minutes. This condensed timeline holds potential for making TMS more accessible to individuals with addiction, minimizing the time commitment required for each session. The data collected from Peter’s brain are helping to test this concept.

“We aren’t targeting the brain circuits as effectively as we could,” Steele says. “We can do this better.”

Not all health care professionals are waiting for those improvements—or for regulatory approval. Already, clinics in the United States, Europe, India, and elsewhere have begun offering TMS services routinely for people with a variety of substance dependencies, using a regulatory loophole that allows for “off-label” uses of drugs and devices approved for other applications. Typically, health insurance doesn’t cover these therapies, so people have to pay the hefty bills themselves, a cost that can reach upward of US $15,000 for an entire course of treatment.

Addiction is fundamentally a disease of malfunctioning brain circuits.

TMS practitioners champion the transformative potential of the approach. “I have seen firsthand the impact that it has,” says Isabel Leming, a mental health therapist in Glasgow. She previously worked at two of the United Kingdom’s largest TMS centers, where she regularly administered the therapy to people with cocaine and other addictions. “It drastically changes people’s lives for the better.”

The stakes are high. According to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, more than 70,000 drug overdoses occur in the United States alone every year. In 2017 (the latest date for which statistics are available), the cost of drug abuse in the United States was nearly US $272 billion, taking into account crime, healthcare needs, lost work productivity, and other impacts on society.

But the TMS procedure also has potential downsides. It can trigger epileptic seizures and memory disturbances. Headaches and scalp discomfort are common. And without an established evidence base for treating addiction, some experts worry that TMS practitioners may be raising false hopes and preying on the vulnerabilities of desperate patients.

“There are TMS clinics cropping up like mushrooms after rain,” says Veljko Dubljević, a neuroethicist at North Carolina State University, in Raleigh. “We don’t know what those clinics are doing in terms of the parameters of stimulation. They may be experimenting on people in that sense.”

Peter, for his part, has no illusions about the brain stimulation that he received. “I know the session is not going to cure me or last a long time,” he says. But he is hopeful that insights gleaned through his participation in a TMS study will help others in the future. “I’ve lost friends and family [to opioid addiction], and I don’t want to see anyone else die.”

Building on TMS’s Short-Term Effects

Perhaps the strongest evidence in favor of TMS for curbing addiction comes from a U.S.-Israeli study of more than 200 chronic cigarette users who had tried to stop smoking in the past, with little success. Trial participants received either daily TMS or sham treatment for three weeks, followed by top-up weekly sessions for three more weeks.

By the end of the study, people who received TMS had higher quit rates and reduced cigarette consumption: Nearly 1 in 3 individuals who completed the full course of TMS therapy managed to abstain from smoking, well above the quit rate of those who received the sham treatment. Based on these results, BrainsWay, the Jerusalem-based company that sponsored the trial, received U.S. authorization in 2020 to market its TMS platform as a treatment for nicotine addiction.

But the treatment is considered only a short-term aid for smoking cessation. Without additional interventions, the majority of quitters tend to relapse within a few months of TMS administration—and that’s true of people with other drug dependencies as well.

“It’s pretty much a short-term effect,” says Tony George, an addiction psychiatrist at the University of Toronto, who has studied the effects of TMS on cannabis use and smoking behavior among people with schizophrenia. “Invariably, once the stimulation goes, the craving comes back very quickly,” he notes. “So we have to find a way to piggyback brain stimulation on top of more enduring treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy or medications.”

That’s easier said than done. Noah Philip is a psychiatrist at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University, in Providence, R.I. He and his colleagues recently completed a small study in which they paired TMS with a cognitive training program. They had hoped the extra brain training would help smokers rein in their worst instincts and “enhance the ability of people to make good decisions,” says Philip. It wound up having the opposite effect.

At the end of the month-long trial, people who received both TMS and the cognitive training had less self-control over their cigarette habit than those who got either intervention on its own. “It’s entirely possible that we’re disrupting something therapeutic or we’re delivering something in a countertherapeutic fashion,” Philip says.

He still thinks that, with the right kind of add-on therapy, clinicians should be able to augment the sobriety-supporting effects of TMS. However, as his study showed, “the [therapeutic] context in which the stimulation is administered really does matter,” he says.

Figuring Out the Hardware

The type of stimulation matters, too. In the United States, TMS is already permitted as a treatment for several psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In Europe, it’s authorized for some neurological conditions as well, including Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis.

In those contexts, clinicians have traditionally administered TMS via flat, butterfly-shaped coils that create focused electric fields at an intensity slightly exceeding the threshold required to produce twitching in a person’s hand. These figure-eight designs are good for targeting specific parts of the brain, but they stimulate the brain only to a depth of a centimeter or two below the scalp.

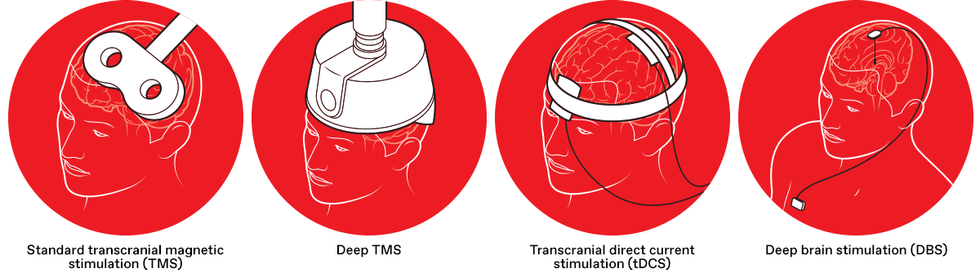

Electric Therapies

Researchers are experimenting with different types of brain stimulation to fight addictions of all kinds. Each type uses electricity to dial up or down the activity of certain neural circuits.

Standard transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses a figure-eight-shaped device to create focused magnetic fields, inducing an electric current in brain areas just beneath the skull. TMS is used clinically to treat depression and other conditions.

Deep TMS uses a helmet with a different configuration of magnetic coils, creating a broad magnetic field to reach deeper brain regions. Deep TMS has been approved in the United States for use as a smoking-cessation aid.

With transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), two electrodes are placed on the scalp to directly apply an electric current between the two electrodes. TDCS has not yet received U.S. regulatory approval for any neuropsychiatric applications.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) requires brain surgery, as electrodes are implanted in the brain to stimulate neural circuits involved with addiction. While DBS has received regulatory approval for other conditions, it’s an experimental treatment for addiction.

Researchers like Steele are hoping to make that system work for addressing addiction, too. But other researchers think that different coil geometries are needed to hit deeper brain regions that control drug-related behaviors. They point to weak neural penetration as one reason a different noninvasive stimulation technology hasn’t worked all that well at combatting addiction. That technique, called transcranial direct current stimulation, or tDCS, involves delivering low-intensity electricity (usually in the range of 1 to 2 milliamperes, applied in 20-minute sessions) via electrodes placed on the scalp. While clinical studies are ongoing and some studies have shown glimmers of promise, tDCS has generally provided little reprieve to people with substance-use issues thus far.

BrainsWay is the largest commercial provider of the deep TMS strategy. When company scientists designed their smoking-cessation device, known as the H4 coil, they sought to target specific brain structures involved in reward processing and craving regulation. The result was a bowl-shaped coil, one that sits inside a cushioned helmet and looks more like a vintage hair dryer at a 1950s beauty salon than like the Mickey Mouse ears of the handheld figure-eight design.

Conceived in large part to stimulate the brain’s insula, a region implicated in drug-seeking behavior, the H4 coil drew its inspiration from the observation that smokers with damage to the insula had an easier time abandoning their cigarette habit. But last year, a team led by Michael Fox, director of the Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, reported that the device may work in a different manner entirely.

Fox and his colleagues interrogated the electric field of the BrainsWay coil and found that it was primarily hitting not the insula but a region in the very front of the brain. That region, called the frontopolar cortex, also happens to serve as a hub for brain circuitry linked to addiction.

“There are TMS clinics cropping up like mushrooms after rain.” — Veljko Dubljević, North Carolina State University

Fox’s team started investigating that area upon examining the brains of people who quit smoking after experiencing localized injuries to the brain. The focal points of brain trauma varied among the individuals, but the different spots all mapped onto a brain network connected to the frontopolar cortex. What’s more, the phenomenon wasn’t limited to former smokers. The team also found that veterans of the Vietnam War who had focal brain damage from old shrapnel wounds showed a lower propensity for alcoholism when the impaired brain region was in the same network.

Findings like those underscore the neurological similarities that drive different addictions. “There is overlapping circuitry for all substances of abuse,” says Tonisha Kearney-Ramos, a neuroscientist at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, in New York City.

Kearney-Ramos and Colleen Hanlon are among the many neuroscientists who now hope to put these insights to good use. A former academic turned industry executive, Hanlon left her post at Wake Forest School of Medicine last year to join BrainsWay as the company’s vice president of medical affairs. Hanlon and Kearney-Ramos are collaborating on research that has similarly pointed toward a single treatment target that “applies to multiple sorts of substance-use populations,” Hanlon says—including people who have problems with alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine.

A common approach to TMS might thus work across substance types. But Hanlon also sees opportunities to tailor the intervention to an individual’s addiction. As research has shown, people who habitually turn to drugs do so for different reasons. Some may seek relief from life’s problems, for example, while others enjoy the euphoria of the experience. These different motivations reflect different brain-activity patterns that may require modulating in different ways, Hanlon says.

Understanding Addiction in the Brain

Going even deeper into the brain than TMS allows remains another option. A handful of pilot studies—from Germany, Canada, the United States, China, and elsewhere—have found that implanting electrodes into neural structures near the center of the brain and then energizing them can help curb drug and alcohol addiction when nothing else works. And it’s possible, notes Fox, that “different people may need different levels of circuit intervention.”

But deep brain stimulation is an extreme measure. It requires that a neurosurgeon drill a small hole in the patient’s skull and then insert electrodes, which are connected via wires to a pulse generator implanted in the chest wall. Given the invasiveness of the procedure, it is unlikely to become a mainstream treatment for the millions who battle substance-use disorders. Plus, it’s still unclear whether this intrusive measure works better than noninvasive approaches like TMS for treating addiction in most people.

That’s because addiction is fundamentally a disease of malfunctioning brain circuits. When people repeatedly use addictive substances, it causes these circuits to go haywire. The task for brain-stimulation researchers remains to find nodes in this aberrant circuitry that can be effectively modified with jolts of energy. This may mean dialing down brain activity linked to craving, or amplifying activity involved in decision-making and self-control. The best spots for inducing these circuit modulations remain unclear.

Uncertainties like those haven’t stopped some clinics from offering brain stimulation treatments for addictions of all kinds. But with so many unknowns, many neuroscientists want to hit the pause button on a mass rollout of these techniques, until further research can bring more scientific rigor to the field. “We’re trying to be slow and methodical,” Steele says.

Which is why, back in Steele’s lab in Hartford, Peter has been asked to look at pictures of different objects and rating the intensity of his cravings for drugs. Telephone, umbrella, piano keys—no craving. Needle in arm, spoon with powder, pill bottle—a little.

Wisps of long gray hair poke out from under the EEG cap that is measuring Peter’s every brain wave. Other study participants underwent the same procedure, but with MRI scans. Steele and his colleagues will later mine these neural-activity readings to better understand the effects that the TMS treatment had on addiction circuits in the brain.

“I don’t feel a difference that would make me not think of drugs and stuff,” Peter says. “But hopefully they can see it with the computer.”

This article appears in the August 2023 print issue.

- Brain Stimulation Gives New Hope For Treating Psychiatric Disorders ›

- Brain Stimulation Improves Memory in Older Adults ›

- Deep-Brain Stimulator Draws Power From Breath ›