Pilot Project Sends Kelp–and Carbon–to the Seafloor

Researchers are scaling up solar-powered kelp farms

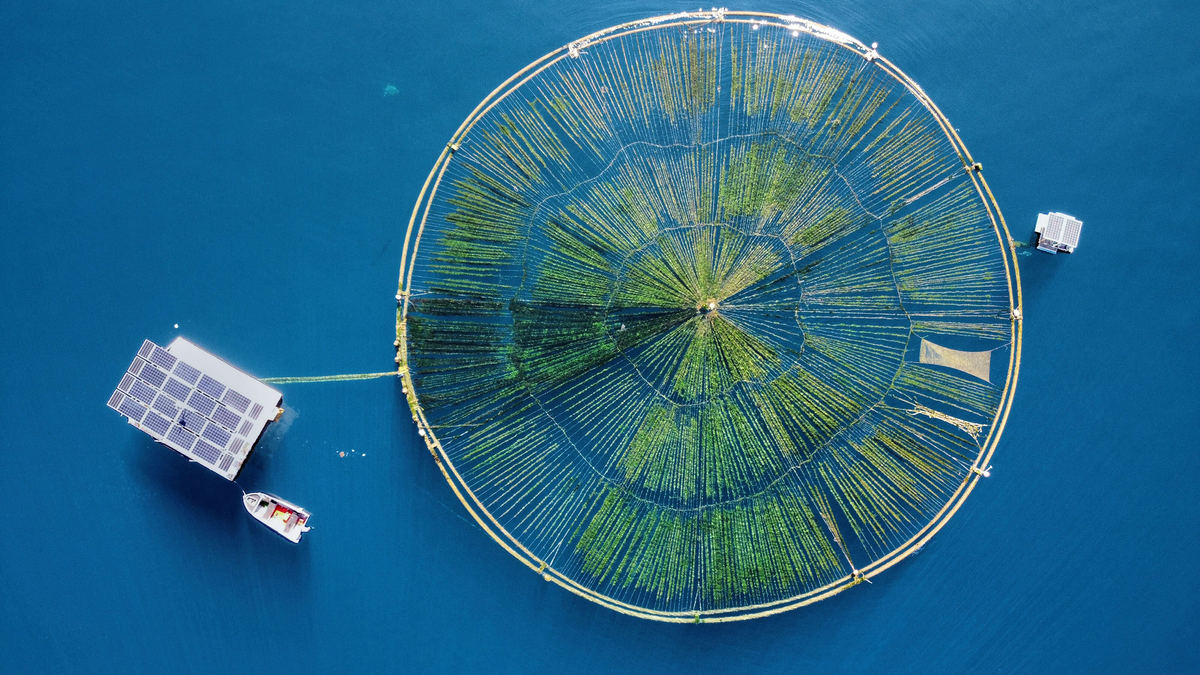

An innovative kelp farm lowers the growing ring to deep nutrient-rich waters every night.

Last January, in the waters off Cebu City in the Philippines, researchers first deployed a huge flexible ring seeded with seaweed and spanned by spokelike ropes and tubes. Every nightfall, cranks mounted on a floating platform lower the ring 125 meters below the surface to expose the seaweed to cooler, more nutrient-rich water. At daybreak, the cranks pull the ring back up to the surface to soak up sunlight and carbon dioxide.

The Climate Foundation, the Seattle-based company behind the project, has found that this deep cycling makes kelp grow three times as fast as it can when kept in shallow waters, as seaweed farmers do now. The extra kelp can be turned into food, fertilizer, and fuel, or it can be committed to the deep, locking away countless tonnes of carbon for centuries.

This article is part of our special report Top Tech 2024.

These conclusions were predicted by the Climate Foundation’s computer models, supported by small-scale tests at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and validated by field tests conducted since 2019 in the Philippines. This year, the startup plans to scale up to a 10,000-square-meter offshore kelp platform, which it expects to be economically sustainable.

“Over the past decade, we’ve gone from designing systems on a chip in Silicon Valley to systems on a ship in the Pacific Ocean,” says founder and executive director Brian von Herzen, who has a Ph.D. in computer science. “It’s our hope in 2024 to validate our model and then, as [they] say in Silicon Valley, design it once and build it a million times.”

The Climate Foundation is one of several startups growing kelp to remove carbon dioxidefrom the ocean. What sets it apart is its ambitious vision of fully automated, solar-powered, floating kelp farms to spur local economies and regenerate marine ecosystems while sequestering carbon. Last April, the plan earned the company a milestone award of US $1 million from the XPrize competition on carbon removal.

“Over the past decade, we’ve gone from designing systems on a chip in Silicon Valley to systems on a ship in the Pacific Ocean.”—Brian von Herzen, Climate Foundation director

The oceans naturally absorb a quarter of the carbon that is released by the burning of fossil fuels. Today, ocean technologies that use chemicals and membranes to absorb even more carbon are getting support from billionaire philanthropists and governments. But growing kelp is a nature-based solution with fewer ecological risks, according to the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

Kelp is the planet’s fastest-growing plant, soaking up 2,200 to 3,000 metric tons of carbon per square kilometer each year—more than tropical rainforests, according to the Climate Foundation. But the seaweed industry is collapsing as climate change warms the upper layers of the ocean, preventing nutrient-rich waters from rising from the depths.

When he started this project back in 2007, von Herzen planned to pump deep water up to the kelp. But his concept has evolved. “That’s like bringing the mountain to Mohammed because it might take a million cubic meters of seawater per day to irrigate a large seaweed operation near the surface,” he says. So his team decided “to bring Mohammed to the mountain” by moving the seaweed meshes up and down.

The platforms have Wi-Fi hotspots, and the team uses a cellular network to remotely control the motors that raise and lower the meshes. In von Herzen’s grand vision, satellite-based Internet could eventually be used to manage global fleets of kelp platforms from shore.

The Climate Foundation harvests seaweed and also lets some fall to the seabed, where its carbon is sequestered.

A quarter of the seaweed grown typically falls off the platform and sinks to the seafloor, von Herzen says. There, seafloor organisms digest the kelp and emit CO2, which reacts with calcium carbonate sediments on the seafloor to form stable calcium bicarbonate. The kelp that the team harvests currently becomes agricultural additives; it could also be used to make biofuels, fertilizers, or livestock feed.

Rod Fujita, director of research and development for EDF’s oceans program, questions the approach of growing kelp for combating climate change. It’s hard to measure how much carbonseaweed sequesters, he notes, because fish and microbes feed on seaweed, then exhale it as carbon dioxide. He also believes it’s better to use kelp than to let it sink. “[The] Climate Foundation is trying to harvest, which is great,” he says. But he believes the best strategy for mitigating climate change with seaweed is to turn it into fuels or plastics, construction materials, or additives that suppress methane emissions from cattle and rice paddies. “Unless they go into these product categories, it won’t have much climate-mitigation benefits.”

This year, von Herzen says they’ll be testing both the technology and the economics. Terrestrial solar is now the cheapest electricity, he says, and marine solar could become even more affordable because there’s no need to purchase land. And the platforms are designed to create a new type of business in the deep sea. “We’re designing an approach and a platform that provides a scalable way of addressing food security and climate gaps,” he says. The technology is “able to use mostly empty ocean.”

This article appears in the January 2024 print issue as “Kelp Farms Make Carbon Capture a Growth Industry.”

Corrections were made to this article in January 2024 to state that the ring is lowered 125 meters each night and to clarify the mechanism by which the CO2 is sequestered on the seafloor.