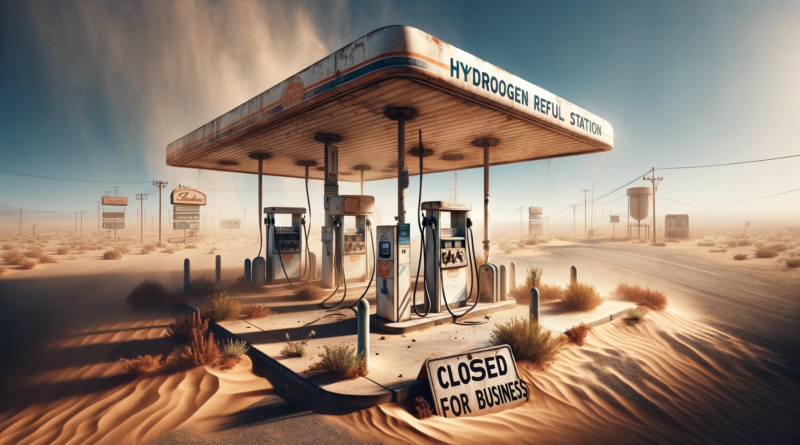

Hydrogen Refueling Station Closures In Multiple Countries More Painful News For Hydrogen Proponents

The past year has been a year of creative destruction in hydrogen for energy efforts. That is to say, destruction of creative accounting and projections in business cases. Green hydrogen supply proposals failed miserably to ignite financial interest as they couldn’t find offtakers for realistically costed hydrogen, with only 0.2% of over 1,300 such deals by volume reaching production.

And along with that creative destruction comes the failure of hydrogen refueling stations. Not the type of failure I assessed recently, where scaling the low volumes of hydrogen dispensed at 55 stations in California would have resulted in approximately 30% of capital expenditures spent on maintenance annually instead of the 3% to 4% figures used for years in total cost of ownership studies. One commenter suggested that they had proven me wrong with linear regression when there is exactly no room to apply that particular technique with the available data, while simultaneously asserting that I didn’t understand statistics, which is par for the course for hydrogen-for-energy advocates in the 2020s.

No, this is stations being shuttered and being dismantled in multiple countries because they don’t make any economic sense. Let’s get at least a partial list together, one which hydrogen ambassadors will attempt to deny or explain away, causing them spikes of pain behind their eyeballs and likely making them snap at random passersby, as I explained in a piece articulating the cognitive dissonance so many of them are suffering. There really is someone with the job title of hydrogen ambassador, by the way, and they are really having trouble wrapping their head around reality.

This is triggered by the news today that Shell is closing its last seven light-vehicle stations in California. At least for now, it’s operating three heavy vehicle refueling stations in the state, three of four in Los Angeles. It’s not clear how long the heavy vehicle stations will be operating given how failure prone heavy fuel cell vehicles have proven to be, with 50% higher maintenance costs than diesel vehicles and double the costs of battery electric, per my assessment of California’s hydrogen bus fleet data.

There are a proposed 250 refueling stations to be built in northern Europe by Jet H2 Energy, a company with a barely existent website, a staff of 10 per LinkedIn, and various combinations of joint ventures with Phillips 66 and EWE. Ten stations were signed up for a year ago. I can find no evidence of them moving forward, and have to assume that the 250 number will turn into zero as well. Who would finance refueling stations in this climate?

The galvanized rubber bubble skin of hydrogen-for-energy types will be in denial about this, but it’s clear that the economics just don’t work for light vehicles at all. Sales of hydrogen fuel cell light vehicles have fallen off the very low cliff, more of a slight curb, from their previous sales highs. The number of light vehicles in operation is low, with hydrogen epicenter California having only 12,000 registered light vehicles. As my assessment of refueling station volumes showed, the average vehicle was only driving perhaps 15 miles a day, a long way under the 37 miles per day average for the USA.

This latest Shell closure is weighing on my mind a bit. After publishing my assessment of refueling, an Oakland, California resident whose job and child rearing require she drive a lot reached out to me to share her state of deep stress. She had leased a Honda Clarity, trying to do the right thing environmentally in a state which has been pushing a bad technology for 20 years despite clear evidence that it was bad technology. When she reached out, she had less than 40 miles of range left in her car and didn’t know how to tell her boss she couldn’t do her job. She was terrified to go to refueling stations shown as open because they were so poorly supplied with hydrogen and so unreliable that by the time she got to them, they were frequently closed.

As of February 2023, there were apparently just over 800 hydrogen refueling stations in the world. The 231 on this list, assuming that there’s some redundancy with California stations that were out of hydrogen and subsequently closed, are about one in four of the total stations in the world.

Imagine being a gasoline car owner and knowing that there was something like a one in four chance that the sole gas station within a reasonable drive of you would be permanently closed or simply out of gas when you tried to use it. Imagine being a fleet owner in this situation.

Welcome to the world of Danish taxi startup Drivr, which had 100 Toyota Mirais as well as about 60 hybrid electric cars it was using to drive paying passengers around. It was completely unobvious to me why any fleet owner, even in 2021 when Drivr acquired the cars, would put themselves in that position, until I looked and found that of course the EU had thrown a lot of money at it, something I’ve documented occurring in countries around the world. Clearly, Drivr is another staging of The Odyssey of The Hydrogen Fleet, and now that it can’t get hydrogen, it will undoubtedly abandon the Mirais.

But similarly to the woman in Oakland, these numbers hide a lot of stress. Drivr’s Danish founders are probably pulling their hair out. Their entire website is touting hydrogen and now they have no hydrogen. Their drivers are probably worse off because there are no cars for them to drive.

There are real human and economic impacts of continuing to push the overcooked noodle of hydrogen up the greased hill of transportation.

And to be clear, this is far from over. This massive, global, cautionary tale on the square wheel of hydrogen for ground transportation has far from run its course even though the data is very clearly in. That the light vehicle market and light vehicle refueling station market has collapsed leaving heartache and economic pain behind does mean that many players and governments have given up on it for heavier road transportation.

San Mateo, California, just committed to spend up to $168 million of other people’s money on up to 108 fuel cell buses, something that they are proudly proclaiming to be the biggest purchase of bad buses in the world. This despite the easily available history of exorbitant costs of hydrogen buses from other counties in California. There are no language or distance barriers in the way of getting the information. In fact, the information is available online for anyone to look at. When I looked at hydrogen fleet maintenance statistics, it took me minutes to find California’s reports.

On that note, the one station that closed in Germany in 2022 has a clear story. Less than a year after paying for a small fleet of buses and a hydrogen refueling station, the station broke down so completely that they abandoned buses and the station entirely. The transit agency was in limbo on whether it would have to repay the millions of governmental money that it had received for the failed trial, and committed to expanding its electric bus fleet. Yet another staging of The Odyssey of the Hydrogen Fleet.

While Shell is out of the light vehicle game, it and others that have closed small stations are still claiming to be interested in the heavy vehicle space. That’s understandable, as there have been a lot of very bad total cost of ownership studies using baseless assumptions and heavy favoritism for hydrogen trucking to put their thumbs on the scale in both directions. Despite that, it’s impossible to make hydrogen trucking total cost of ownership come remotely near battery electric trucks.

I’ve had a bit of a string of looking at TCO studies in the past few months. The International Council on Clean Transportation published one in November 2023 that I assessed that was obviously deeply wrong with the most superficial of glances, finding that hydrogen trucks would have energy for distance traveled costs only a small bit higher than battery trucks, despite both using electricity at refueling stations. There were multiple thumbs on that scale, something that they pulled back from without really admitting that they’d pulled back from, changing all their numbers and conclusions and saying that they’d added an appendix due to interest in the report.

A German working group report I assessed had to assume pipelines for hydrogen were running to every building and that hydrogen gas utilities would be as prevalent as natural gas utilities are today to get hydrogen trucking costs down out of the stratosphere and still found that battery electric trucks were cheaper.

This morning I looked at a 2021 study, less than three years old, from the United State’s Argonne National Laboratory on hydrogen vs battery electric vehicles. Same kind of problems. They were assuming flat battery energy densities through 2050 and increasing hydrogen storage densities. They were assuming hydrogen fuel cell vehicles would be sold by the millions to bring the cost of fuel cells down, ignoring the platinum and membrane costs that are relatively inflexible. They were assuming it was possible to get to US$5 per kilogram hydrogen delivered. They assumed battery electric components and fuel cell components were equal price as at the time of the study and would decline in lockstep, when battery electric vehicles had already demonstrably shown that they were going to dominate. They were using older US DOE wishful thinking targets with no basis in empirical reality when US DOE hard numbers were available.

These kinds of problems are rife in the literature. A lot of it, as I’ve written, comes down to believing the nonsense projections of massive aviation and shipping growth and so assuming biofuels couldn’t possibly scale. As such, hydrogen becomes the only alternative, and then they twist themselves into pretzels to try to justify how this can be remotely economically feasible.

So, hydrogen for light vehicles is going as has been completely obvious since at least 2012 when the Tesla Model S launched. It’s taken a while, but the entire market is collapsing. With now four mid-sized battery electric delivery vans available for under $100,000 with 400 km range, that market is dead as well unless governments throw lots of money at a hydrogen fleet.

A bunch of people are holding out hope for hydrogen in Class 8 / N3 trucks, the biggest ones, but total cost of ownership studies, even with lots of thumbs on the scale, are finding that they are uneconomic as well compared to battery electric. The same is happening for trains, by the way.

Europe is in theory building hydrogen refueling stations every 200 kilometers along their TEN-T Core road network. I’ll believe that when I see the stations being built, and I’ll believe that there’s a lasting place for hydrogen in trucking when they’ve been operating for ten years. The former will quite likely happen to a considerable extent at €3-5 million per station because there is a lot of inertia behind hydrogen trucking despite clear reasons to go full throttle to battery electric.

After all, Daimler keeps spending money in the space with a Board member posting about it and defending their choices with no data just words on LinkedIn and presumably elsewhere, and more remarkably firms are actually giving Nikola money for fuel cell trucks, usually based on really bad information and assumptions. That’s not going to end well for them.

But every one of these failures has a human story or many human stories behind it. The deeply stressed mother in Oakland is only the tip of the iceberg. There are talented young people who have warped their careers toward these spaces who are starting to have premonitions of impending economic disaster. There are people who have become accustomed to steady work fixing refueling stations.

The pain and stress it will cause can be laid in part at the feet of people who did not change their minds when the facts changed, but stayed the course after 25 years of failure. They are in governments and research organizations around the world. One hopes they’ll look in the mirror, reconsider their past decade of effort and pivot to more productive ends. Or at least publish retractions or serious updates of their bad reports making hydrogen for transportation seem viable.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.