Tesla Miles Traveled

Encouraging new evidence on eVMT.

Today’s post is co-authored with Duncan Callaway

The parking lot at our Berkeley grocery store, the one with kombucha on tap, is increasingly populated with electric vehicles (EVs). This feels like a step in the right direction. Moving people out of their gasoline-powered cars and into EVs will likely be key to reducing carbon emissions in the transportation sector.

It’s one thing to see EVs taking over the Berkeley Bowl parking lot. But what about the Mall of America?

To meet our decarbonization goals, we’ll need to convince the masses, not just the Berkeley eco-warriors, to make the EV switch. This mainstream transition is not going to happen if EVs are poor substitutes for the gas-powered cars that Americans know and love.

As Catherine and co-authors note in their blog, one way to start assessing this real-world substitutability is to ask if Americans are driving their electric cars as much as gas-powered cars. This week’s blog unpacks the latest electric-fueled vehicle miles traveled (eVMT) data from the largest EV market player…

Alternate perspectives on eVMT

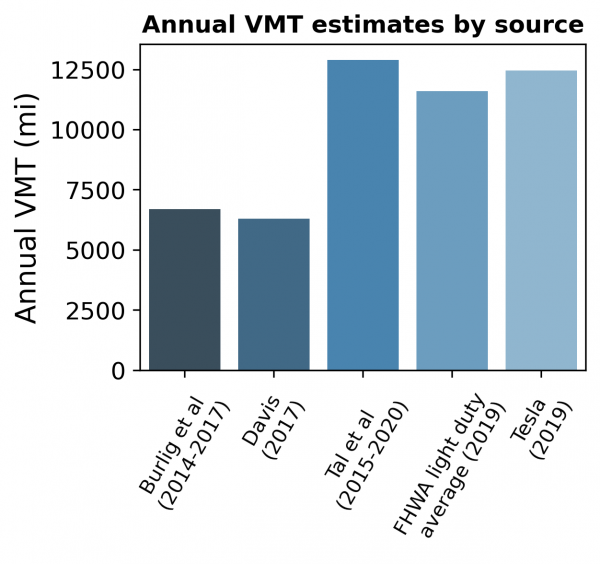

Some recent studies have investigated how much Americans are driving their EVs. To put these numbers in perspective, the Federal Highway Administration estimates that US light-duty vehicles were driven, on average, 11,467 miles in 2017 and 11,599 miles in 2019:

- Lucas Davis estimates that the 436 electric vehicles in the 2017 National Household Travel Survey drove an average of 6,300 miles per year.

- Gil Tal and co-authors used data loggers to track miles driven by 358 California EV drivers. These study participants traveled 12,900 EV miles per year on average.

- Noting limitations with small and non-random samples, Catherine, Jim Bushnell, and co-authors (Burlig et al.) estimate residential EV charging using the electricity bills of PG&E customers (including over 57,000 EV and PHEV drivers!) from 2014-2017. They estimate that, on average, battery EVs travel 6,700 miles on electricity per year.

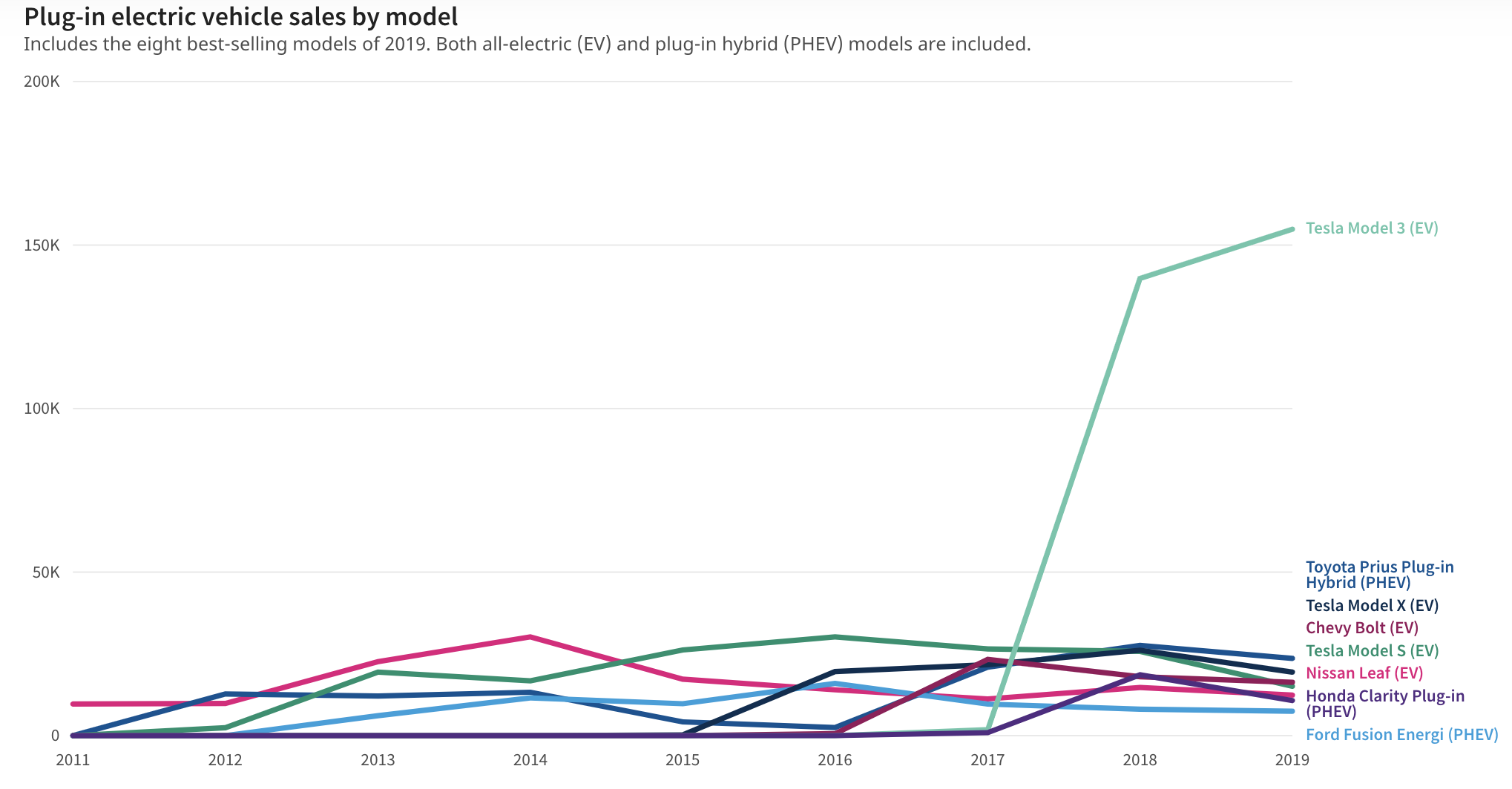

These retrospective studies are insightful. But projecting forward is complicated by the fact that the EV market landscape is changing fast. Tesla blew the doors off this market in 2018 with its Model 3, as the figure below shows. Last year, 79% of all EVs registered in the United States were Teslas.

The eVMT studies to date use data that largely pre-date this Tesla take over. This has us wondering…what’s happening to eVMT now that EVs are more sleek than science-project?

Tesla Miles Traveled

A growing number of auto manufacturers, including Tesla, are selling cars with built-in internet connections. This enables cool features like access to real-time traffic data, over-the-air software updates, and caraoke!

On-board telemetry also allows car manufacturers to capture information on vehicle usage and performance. We asked Tesla if they might share some of what they know about how their cars are being driven. They generously sent us summary statistics for daily miles driven, by model and year.

The figure below summarizes these aggregated Tesla miles traveled (TMT) data for 2019. For each reporting year, we received statistics for all Teslas delivered in the US over the previous two years, for which there were at least 30 days of data (note the sales figures above — this is a lot of cars, dominated by the Model 3). So when you’re looking at the 2019 average, that’s summarizing information for cars delivered between January 2018, and December 1, 2019.

We contrast the Tesla numbers (from 2019) with the national average VMT from FHWA and other empirical eVMT estimates. On average, the Tesla cars are driven about the same as a typical light-duty vehicle in the US, and a lot more than some prior estimates based on pre-2018 data.

Figure note: Because cars in the Tesla data were owned for fractions of a year, they provided us with daily mileage data; we multiplied by 365 days/year to make the data comparable to other reports. But it’s important to keep in mind that we’re not doing anything to correct for seasonality, or the possibly changing habits of drivers over the course of the sampling period. Empirical eVMT estimates are from the Gil Tal et al. study, Burlig et al., and Lucas Davis’s paper (all referenced above).

Figure note: Because cars in the Tesla data were owned for fractions of a year, they provided us with daily mileage data; we multiplied by 365 days/year to make the data comparable to other reports. But it’s important to keep in mind that we’re not doing anything to correct for seasonality, or the possibly changing habits of drivers over the course of the sampling period. Empirical eVMT estimates are from the Gil Tal et al. study, Burlig et al., and Lucas Davis’s paper (all referenced above).

We’re going to go out on a limb and conclude that, when it comes to eVMT, vehicle attributes matter. Many of the EVs in earlier studies were low range (e.g. less than 100 miles per charge). The Tesla models in our data have 250-400(!) miles of range. But range may not be the only factor driving higher TMT. For example, Tesla’s extensive super-charger network could be playing a role, and its styling and acceleration may be drawing a different profile of driver.

Tesla also sent us some information on the distribution of driving patterns for their cars. We’ll save a detailed analysis for another day, but the short story is this: the median Tesla goes farther per year than the median gas-powered car. The reason the averages are comparable is that there are a few gas-powered cars that go really far per year (hundreds of thousands of miles), which lifts up the average.

On-board policy navigation?

With practically everyone jumping into the EV game (Ford, VW and Volvo recently released new models), we’re curious to know whether the driver behavior we’re seeing in the Tesla data will extend to all EVs with mainstream appeal.

Beyond our quirky curiosity, these questions are increasingly policy-relevant. The Biden administration is proposing to spend billions to help Americans make the switch to electric cars. This includes funding for EV tax credits and expanding the charging network. To effectively target and evaluate these investments, we’ll need to understand how people are purchasing and driving these cars.

Now is the time to open the conversation about how we might use these data to shape and steer policy while also respecting privacy and intellectual property. There are good examples of other market contexts in which firms share important data in the public interest (e.g. household consumption data, labor market data, mortgage market data). Our networked cars can route us out of traffic jams — can they help us chart our vehicle electrification course?

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Callaway, Duncan and Fowlie, Meredith. “Tesla Miles Traveled” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, June 21, 2021, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2021/06/21/tesla-miles-traveled/

Categories

Source

Source

No government should never tax or trouble EV owners for ANYTHING. What are we trying to accomplish here? Tax Exxon.

The problem with using the pre-2018 EV data is that the buyer subgroup is almost certainly different than the broader population. This subgroup is much more likely to be environmentally conscious and to live in an urban area. That means that they already drove fewer miles per year. The correct comparison is a paired match of the mileage for either their previous car or households with the same characteristics. Tesla broke out of that mold (just see all of the Tesla’s driving on the freeways and parking in the expensive parts of town.)

Reads a little too much like an ad for Tesla. I have major concerns with relying on industry supplied data, summary statistics yet.

Until EVs become more than a tiny nitch (mostly luxury) market it is hard to generalize to the general population.

How to use the data:

1: charge DMV fees on miles driven basis. Allocate to municipalities based on where driven – ie if on highways, pay the state. If city streets send the money to the municipalities maintaining those streets.

2: Dont need FASTRAK – cars can self report, automatically, their HOV usage.

3: add charging ‘tracks’ on highways – running out of charge, shift over to the side-lane with charging ‘tracks’ – sort of like the track that move cars through carwashes: a bushing drops down to make electrical contact. Details re: technology and safety etc can be worked out.

A few months ago I checked mileage on used Teslas on Carvana and came up with about 6500 miles per year. As a simple comparison another EV, the Nissan Leaf, averaged 8500 miles per year. I suspect many Tesla owners have multiple vehicles and do not use them for daily drivers.

It’s good to have newer data coming in. Others have written that the 2014 – 2017 data was influenced by a lot of $199/month Leaf leases, and those cars, with less than 100 miles of range, were used almost exclusively for short commutes. My neighbor here in Olympia, a school teacher, bought a used Leaf with 30,000 miles on it for $5,000, and it works great for her commute. Her husband’s Subaru does all the freeway driving, but the Leaf, charging overnight on 120V, works great for her to get to work, the supermarket, yoga class, book club, and the gym.

The California EV market data is further skewed, in the short run, by two factors which suggest that future VMT by EVs will be different.

The first of these is the move by Uber and Lyft to encourage their drivers to choose EVs. These cars are driven A LOT. Full-time TNC drivers (the most likely to buy an EV) are driving 200 – 300 miles per day. Think of that as five round-trips to the airport from the suburbs a day, and it’s not a surprise. Many of these choose Tesla for the availability of supercharger stations (predictable and reasonable price) as opposed to a Bolt or Niro, where you pay Blink or Chargepoint rates. Plus, even a Tesla 3 qualifies for “Uber Black” with premium rates. There’s an interesting economic study to be done here on customer response to the pricing of DC Fast Charging service. If you’ve been spending $300/week for gasoline, and can buy a Tesla that costs half that amount per mile for fuel, the $600 monthly payment on the Tesla is a break-even, and when you avoid an oil change in the second week, you’re money ahead. Best if you live in Alameda, Santa Cruz, SVP, or another municipal utility service area.

For a sense of how creative these drivers become, listen to the “best hits” of a series of podcasts interviewing Uber and Lyft drivers who choose EVs: https://forthmobility.org/why-electric/rideshare-drivers/Podcast They charge 2-3 times per day, being careful to not go below 20% or above 80% to conserve battery life, know where all the free chargers are (and park there during lulls in available ride requests), and can tell you to the penny how much they are saving per mile and per week by using electricity instead of petrol.

The second is the cool factor — people with no need for “another” car to go with their BMW X3, Boxster, F-150, and Sprinter, but they “gotta have” a Tesla. Those cars are driven very little. The X3 goes skiing, the Boxster gets the sunny days on the coast highway, the F-150 is to pull the fifth wheel, and the Sprinter is to transport the recumbent E-trikes to the rail-trail. There’s only so many miles that the 1% and 3% can drive, but no limit to how many vehicles they can own (think Jay Leno here). My friend Gene is one of these, and his 2-year old Tesla 3 has 5,500 miles on it. The rest of his fleet is a Boxster and an X3, plus a Honda Odyssey that lives at his winter home in Palm Springs. His E-Bike is probably getting as many miles as any of his four-wheelers.

We’ll start getting more and more meaningful data as sales increase and “ordinary” folk become a significant part of the owner pool. But remember, the 10% of cars most driven cover about 40% of the miles driven, so if we can penetrate that market — and the TNCs are a big part of it — we’ll see VMT increase.

If you get a long range EV such as the 300 miles range Teslas there is no need to charge at stores inside your daily travels and you can charge at home. I charge my Tesla using my own solar panels. I only put about ten miles per day on my Tesla driving around Austin. I used to drive to stores more before covid 19 but now I shop on line mostly – amazon….Gene Preston https://egpreston.com