Climate Change Had Its Day in Court

Back in November 2014, I wrote about how Mass Energy has joined with the Conservation Law Foundation in a lawsuit...

Recently, we posted a blog on one policy, the Clean Heat Standard, to decarbonize the building sector. Consider it one tool in the tool chest and understand that it’s usually not possible to make anything with just one tool. With this blog, we will explore a complimentary policy – Building Performance Standards (BPS).

Briefly stated, BPS require building owners to report their energy use and/or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to a local or state agency, and then reduce those emissions over time according to a set of standards. The standards gradually become more stringent over time, giving owners plenty of forewarning and some flexibility. These standards apply to existing buildings, which is important because about 70% of our building stock in 2050 is in place today. Furthermore, any building built between the time a BPS goes into effect and 2050 would have to comply. That sends a signal to new construction decision-makers that they should think twice about installing fossil-fuel-based heating systems.

Why do we mention 2050? It’s because both Massachusetts and Rhode Island have laws on the books saying that GHG emissions will have to be net zero by 2050. The laws also mandate that GHG be reduced by 2025 and 2030, so policies that go into effect soon can help meet requirements for those years too (at Green Energy Consumers, our view is that if we fail to hit our 2030 target, our chances of being net-zero by 2050 would be slim).

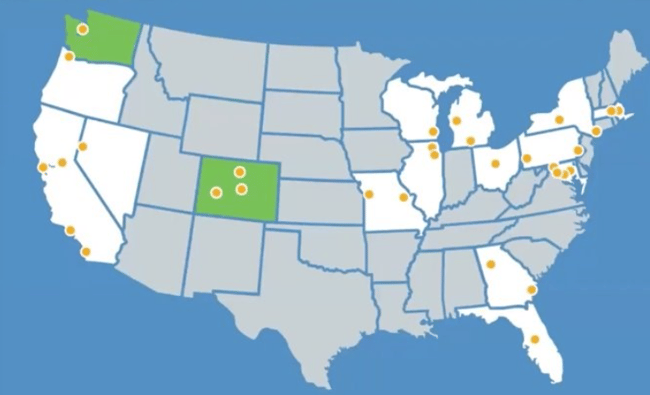

BPS is not a new idea that we invented. There are some international examples, and according to our friends at the Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnership, 33 American states and localities are working on BPS.

From the map, you can pick out Boston, which started with BERDO, a Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance, and graduated to the same acronym, but with the name, Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance. Appropriately, BERDO regulates large buildings, meaning non-residential buildings of 20,000 square feet and up, and residential buildings that have 15 or more units. All such buildings will have to be net zero by 2050, but the pace at which a particular building will have to reduce its emissions will depend upon its use category, such as; assembly, college/university, education, food sales/service, health care, lodging, manufacturing/industrial, multi-family housing, office, retail, services, storage, and technology/science.

From the map, you can pick out Boston, which started with BERDO, a Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance, and graduated to the same acronym, but with the name, Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance. Appropriately, BERDO regulates large buildings, meaning non-residential buildings of 20,000 square feet and up, and residential buildings that have 15 or more units. All such buildings will have to be net zero by 2050, but the pace at which a particular building will have to reduce its emissions will depend upon its use category, such as; assembly, college/university, education, food sales/service, health care, lodging, manufacturing/industrial, multi-family housing, office, retail, services, storage, and technology/science.

Strict building energy codes are important for sure insofar as they affect new construction and major renovations. But for existing buildings, we need a strong policy guiding retrofits because, as stated above, buildings last a long time and most of what we have today will be standing in 2050. According to the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2025 and 2030, large buildings account for just five percent of all buildings, but 30 percent of the total built space, a whopping 150 billion square feet. Over time, a BPS could be amended to include somewhat smaller buildings, but starting at the largest makes sense.

A huge benefit of BPS is that it addresses an age-old conundrum that we call the “landlord/tenant split incentive.” In almost all cases, a tenant has no way to make their space more energy efficient. Even if the tenant did have the resources, it is hard to justify making a hefty investment if the lease is short-term. Green Energy Consumers is a case in point. We have 5-year leases with our landlords in Boston and Providence.

The split incentive is why rented spaces tend to use more energy per square foot than owned spaces. A BPS puts the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of the landlord. It gets that key job done. In the long run, both owners and tenants will benefit from greater efficiency.

Boston adds a component related to the equity that ought to be replicated. In Boston, large building owners can comply either by reducing their emissions directly or by making Alternative Compliance Payments to mitigate residual emissions, at a price of $234 per metric ton of CO2e (which will be reviewed every five years). Funds generated from these payments will be placed into an "Equitable Emissions Investment Fund" to support, implement and administer local emissions reduction projects within Boston, prioritizing Environmental Justice communities and local renewable energy development.

In August, Governor Baker signed a major climate bill, An Act Driving Clean Energy and Offshore Wind Forward. We like that bill for several reasons, one of which is that it establishes a statewide building energy benchmarking requirement. The bill will require that owners of buildings larger than 20,000 square feet annually report their energy consumption to Massachusetts’ Department of Energy Resources (DOER) by June 30th each year. DOER will make the resulting data public by October 31st of each year. The measure was sponsored by State Senator Becca Rausch.

This provision in the climate bill is an important step toward reducing emissions from large buildings. We can expect some building owners to find cost-effective ways to reduce their energy use and emissions just by analyzing the data they compile for submission to the state. But reaching the Commonwealth’s target of 50% emission reductions by 2030 will likely require more than a nudge. Perhaps 2023 will be the year to go a step further towards actual emission standards commensurate with the Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2025 and 2030.

In 2022, State Representative Rebecca Kislak sponsored H. 7580 to require the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources (OER) to track the energy use of buildings above 20,000 square feet. By 2028, the pool of buildings required to benchmark would widen to those above 15,000 square feet. And eventually, large building owners would have to reduce emissions over time by an amount determined by OER, and they would have the option of paying an Alternative Compliance Fee. The bill was kept in the House Environment Committee for further study. On the bright side, it was not voted down, so hopefully, it can pass in 2023.

If you would like to learn more about BPS, watch this video of a webinar we produced last April with Representative Kislak and Senator Rausch. Setting a Standard for Cleaner Buildings.

Both Massachusetts and Rhode Island have passed binding laws mandating GHG emission reductions, with stringent requirements for 2025 through 2050. Nonetheless, those laws themselves don’t specify exactly how to reduce emissions by the requisite amounts in the building sector. There needs to be follow-up legislation and/or regulations written by the executive branch. It’s difficult to imagine how building emissions can be reduced enough, on schedule, without buildings performance standards and a Clean Heat Standard. So, let’s make them happen in 2023.

Join us on October 3rd at Lawn on D. Get your tickets today!

Back in November 2014, I wrote about how Mass Energy has joined with the Conservation Law Foundation in a lawsuit...

This blog covers strategies outlined in Massachusetts’ final Clean Energy and Climate Plan (CECP) to reduce...

Comments