“We’re never going back,” declare Jonathon and Cory Drayer of Fredericksburg, Va. The couple recently traded their SUVs for electric vehicles( EVs), and happily swore off ever buying another internal-combustion engine (ICE) powered vehicle again. Jonathon and Cory are among the vanguard of a much hoped-for change: the EV-only family.

Their switch to EVs was also providential. After moving to a home much further away from their respective workplaces, each would have become part of the gasoline “superusers” club. Superusers make up the 10 percent of U.S. motorists who, according to a study by the environmental group Coltura, drive 30,000 miles or more a year and use an estimated 32 percent of all gasoline. That gasoline consumption is more than the bottom 60 percent of U.S. drivers combined, Coltura says.

The EV Transition Explained

This is one in a series of articles exploring the major technological and social challenges that must be addressed as we move from vehicles with internal-combustion engines to electric vehicles at scale. In reviewing each article, readers should bear in mind Nobel Prize–winning physicist Richard Feynman’s admonition: “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for Nature cannot be fooled.”

Getting superusers into EVs as soon as possible, Coltura argues, is essential for the United States to reach its 2030 decarbonization objectives. Transportation is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 27 percent of total GHG emissions in the United States and a similar amount in Europe. Passenger cars and light-duty trucks account for about 57 percent of those totals. Transitioning from ICE vehicles to EVs is one important way to reduce these emissions. Therefore, Coltura asserts, instead of offering EV incentives to everyone who purchases an EV, generous incentives should instead be targeted at the estimated 25 million gasoline superusers. As technology historian Melvin Kranzberg has observed, “Although technology might be a prime element in many public issues, nontechnical factors take precedence in technology-policy decisions.”

For example, governmental policies and subsidies intended to encourage the use of electric vehicles and discourage ICE vehicles must encompass the 260 million-plus privately owned vehicles in the United States alone, and eventually the other 1.2 billion vehicles owned worldwide, both numbers that will keep growing. The volume of EV offerings from legacy and startup vehicle manufacturers must expand rapidly to meet the policy-driven ICE replacement requirements. Then there is the willingness of hundreds of millions of ICE vehicle drivers the world over to alter their personal behaviors, lifestyles, and for many their livelihoods, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Rural areas make up 86 percent of U.S. land area, and 60 million people reside there. They cannot be ignored in the EV transition.

When 10 percent of drivers use a third of all gasoline, one must consider the mainly rural areas where they reside and the pickup trucks and SUVs they likely drive. For example, with 13 percent of its drivers using 37 percent of the state’s gasoline, Wyoming is second on Coltura’s list of states with the highest percentage of gasoline superusers. Consider further that nine out of the 10 most popular Wyoming vehicles are pickup trucks or SUVs, with over 280,000 pickup trucks and 240,000 SUVs registered in the state.

Getting Wyomingites into EVs will be tricky. There were only 456 electric cars and light trucks registered statewide as of March 2022, with 95 being non-Tesla vehicles. Not surprisingly, nearly all of the state’s existing 169 public EV charging ports, 75 of which are faster chargers, are part of the Tesla charging network. The lack of EV charging opportunities is endemic across rural areas.

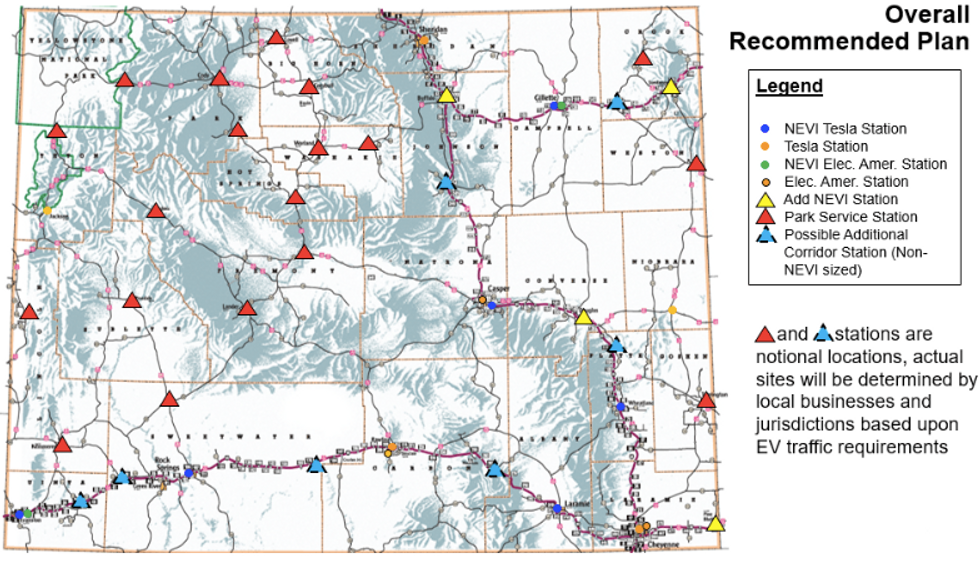

The Wyoming Department of Transportation submitted its National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Deployment Plan to the Federal Highway Administration in June. The plan detailed how the state would use its US $24 million allocation from the $5 billion committed in the federal Infrastructure, Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) as well as the $1.2 million from the Volkswagen diesel scandal settlement to place EV charging stations every 50 miles across Wyoming’s 913 miles of interstate highway.

Woe is Wyoming

There is a hitch in the plan, however. Wyoming’s NEVI plan states that the IIJA charging station requirements to receive funding “would not allow any single NEVI-sized station to be profitable in Wyoming until the 2040s.” Since the state “has no desire to establish infrastructure that will likely fail,” it requested a waiver from the federal requirements to better serve not only Wyomingites’ EVs but also tourists’ EVs visiting the state’s ski resorts and national parks like Yellowstone. New EV-charging stations near tourist attractions are expected to see the most use for at least the next several years.

In September, the Federal Highway Administration

approved $9.7 million for Wyoming’s plan but refused to grant 8 of the 11 EV station waivers it requested. Wyoming will start developing the seven of its proposed EV-charging stations that meet IIJA requirements next year, but it remains to be seen whether any future federal monies will be provided if Wyoming can’t get the denied waivers overturned.

The predominance of Teslas in Wyoming mirrors another reality for most gasoline superusers. Coltura found that superusers generally have the same economic status as non-superusers, with a household median income of around $70,000. However, their income lags in relation to EV owners, whose household median income of around $100,000 means they fall in the top third of U.S. households.

Battery-electric-vehicle owners “earn a lot more than not just the U.S. population but [also] the population of new vehicle buyers,” says Alexander Edwards of Strategic Vision, a firm that helps companies understand human behavior and decision-making patterns.

Edwards adds, “They’re buying these vehicles not just for their environmental friendliness, although that is a nice thing to have, but they are really buying them for their superior acceleration that outperforms other vehicles.”

Battery life, reliability, and charging infrastructure are going to be factors in convincing rural owners of internal-combustion engine pickup trucks to switch to EVs.

Meanwhile, the average Tesla owner’s income approaches $150,000, which puts them in the top 20 percent of U.S. households. Wyoming gasoline superusers seeking the capabilities of ICE SUVs and pickups might find these EVs beyond their means, despite generous incentives.

Coltura’s analysis indicates that 9 percent of U.S. gasoline superusers drive Ford F-Series pickups. Let’s imagine that the approximately 2.5 million Ford F-Series gasoline superuser pickup drivers in the United States decided to purchase the new Ford electric F-150 Lightning. It would take more than 15 years at Ford’s announced production rates to replace them all. Nor is there an obvious plan for convincing the owners of the other 13.6 million non-superuser F-Series vehicles on the road to replace them with equivalent EVs that Ford plans to introduce.

About 200,000 people have placed orders for the Lightning, but Ford CEO Jim Farley revealed that only about “30 percent is (from) F-150 customers…70 percent are new to the brand and new to pickups.” Reportedly, some 40 percent of orders are from those who already owni EVs, with a sizable chunk probably being Tesla owners wanting more cargo space. Jonathon, who owns a Tesla, has ordered a Chevrolet electric Silverado RST for that exact reason. Even more gasoline superusers drive General Motors vehicles than Fords—there are 22.1 million current owners of GM full-size pickups and SUVs—so GM faces similar challenges persuading its legacy customers to switch to EVs.

Rural driving requirements are different

Wyoming gasoline superusers and others in states like Idaho, Montana, and South Dakota are likely to have additional concerns about buying EVs. For instance, a Ford-150 superuser buying a Lightning and driving it the same number of miles will find that their battery warranty will expire in about 3.5 years. High mileage driving in harsh terrain and climate conditions in western states are unknown factors on battery life, as is the eventual cost of replacing a Lightning battery pack, which runs from current estimates of $28,556 to $35,960. Even average Wyomingites keep their vehicles for 14 years and drive an average of nearly 17,000 miles a year.

Battery life, reliability, and charging infrastructure are going to be factors in convincing rural owners of ICE F-150s to switch to EVs, especially if they need to tow trailers. Ford’s Farley acknowledges that in mountainous states, driving requirements are “different than how we’ve designed (our EV) vehicles so far.”

Another potential bump in the road: EVs are designed for over-the-air software service and feature updates, but cell service can be highly unreliable in rural areas. Lengthy trips to dealers are inevitable given the current poor software reliability of EVs, assuming there are nearby dealers to support them.

Furthermore, rural residents tend to be less supportive of climate action than are urban residents, even controlling for political partisanship and other demographics. Appealing to them to convert to EVs for the good of the environment is not likely to be enthusiastically received.

One might object to this analysis on the grounds that Wyoming is an outlier, and that the EV transition will be easier in other states. The issue is not Wyoming per se but rural communities in general, their driving requirements, and the capability of the electrical grid to support EVs at scale in those communities. Rural areas make up 86 percent of U.S. land area, and 60 million people reside there. They cannot be ignored in the EV transition.

It’s an understatement to say that it is crucial to coherently manage the totality of the risk ecology associated with the transition from ICE vehicle to EV ownership.

Besides, getting rural gasoline superusers to give up gasoline-powered SUVs and pickups might be only marginally harder than motivating the overall driving populace, which also likes to drive SUVs and pickup trucks, to switch. Potential EV owners desire an acceptable level of risk or security when purchasing a vehicle. They want a long-lasting, reliable vehicle that meets their specific needs at an affordable price and one that can be refueled with minimum effort—like the vehicle they have now. They may compromise some, says Strategic Vision’s Edwards, but not much.

And if they don’t perceive an EV purchase to have an acceptable risk, it will be nearly impossible to get the 60 percent of U.S. households with two or more ICE vehicles to feel confident enough to become EV-only families. Even among current EV owners, only about 10 percent are EV-only households.

Can governmental EV policies achieve this level of acceptable risk, given the countless swirling crosscurrents of competing and conflicting interests that EVs at scale present?

The answer to this question is especially important in the United States, given that EV policies underpin the Biden administration’s economic transformation plans. EVs at scale are not merely a new technology introduction, like the switchover to high-definition TV or a new civil-engineering project like building the U.S. interstate highway system. EVs at scale have substantially greater impacts on far more industries, social and political structures, national and global economics, security and political competition, and of course the global climate.

It’s an understatement to say that it is crucial to coherently manage the totality of the risk ecology associated with the massive social, economic, political, and environmental adjustments initiated by the transition from ICE vehicle to EV ownership.

As Larry Burns, a former GM executive told the Wall Street Journal, there is a “Rubik’s cube of complexity” of policy and its implementation that requires thoughtfully sorting through all the risk and benefit trade-offs involved.

In the next several articles of this series, we will continue to explore the multiple social infrastructure challenges to transitioning to EVs at scale, beginning with the policy challenges.

- The EV Transition Explained ›

- The EV Transition Explained: Battery Challenges ›

- The EV Transition Explained: Can the Grid Cope? ›

Robert N. Charette is a Contributing Editor to IEEE Spectrum and an acknowledged international authority on information technology and systems risk management. A self-described “risk ecologist,” he is interested in the intersections of business, political, technological, and societal risks. Charette is an award-winning author of multiple books and numerous articles on the subjects of risk management, project and program management, innovation, and entrepreneurship. A Life Senior Member of the IEEE, Charette was a recipient of the IEEE Computer Society’s Golden Core Award in 2008.