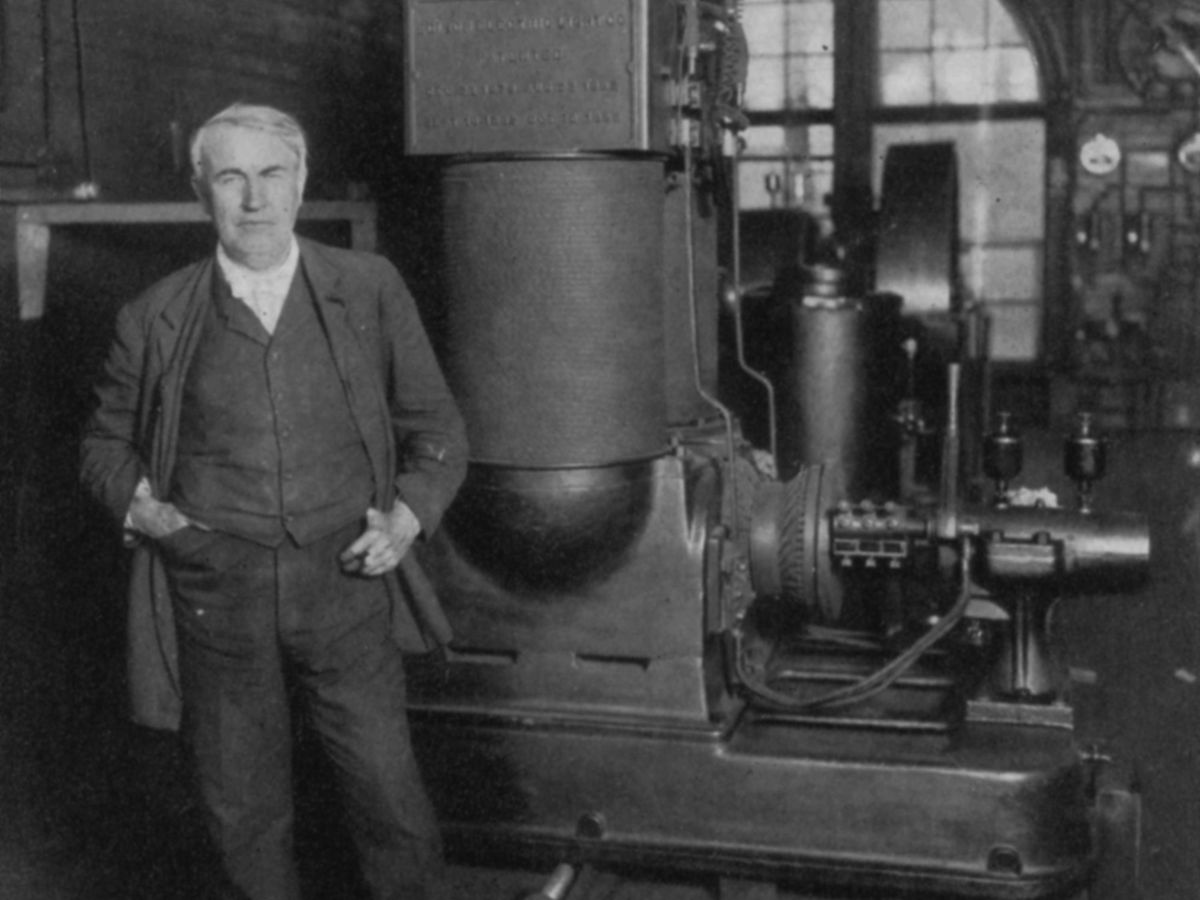

One hundred and forty years ago, Thomas Edison began generating electricity at two small coal-fired stations, one in London (Holborn Viaduct), the other in New York City (Pearl Street Station). Yet although electricity was clearly the next big thing, it took more than a lifetime to reach most people. Even now, not all parts of the world have easy access to it. Count this slow rollout as one more reminder that fundamental systemic transitions are protracted affairs.

Such transitions tend to follow an S-shaped curve: Growth rates shift from slow to fast, then back to slow again. I will demonstrate this by looking at a few key developments in electricity generation and residential consumption in the United States, which has reliable statistics for all but the earliest two decades of the electric period.

In 1902, the United States generated just 6 terawatt-hours of electricity, and the century-plus-old trajectory shows a clear S-curve. By 1912, the output was 25 TWh, by 1930 it was 114 TWh, by 1940 it was 180 TWh, and then three successive decadal doublings lifted it to almost 1,600 TWh by 1970. During the go-go years, the 1930s was the only decade in which gross electricity generation did not double, but after 1970 it took two decades to double, and from 1990 to 2020, the generation rose by only one-third.

As the process began to mature, the rising consumption of electricity was at first driven by declining prices, and then by the increasing variety of uses for electricity. The impressive drop in inflation-adjusted prices of electricity ended by 1970, and electricity generation reached a plateau, at about 4,000 TWh per year, in 2007.

The early expansion of generation was destined for industry—above all for the conversion from steam engines to electric motors—and for commerce. Household electricity use remained restrained until after World War II.

Household electricity use remained restrained until after World War II.

In 1900, fewer than 5 percent of all households had access to electricity; the biggest electrification jump took place during the 1920s, when the share of dwellings with connections rose from about 35 percent to 68 percent. By 1956, the diffusion was virtually complete, at 98.8 percent.

But access did not correlate strongly with use: Residential consumption remained modest, accounting for less than 10 percent of the total generation in 1930, and about 13 percent on the eve of World War II. In the 1880s, Edison light bulbs (inefficient and with low luminosity) were the first widely used indoor electricity converters. Lighting remained the dominant use for electricity in the household for the next three decades.

It took a long time for new appliances to make a difference, because there were significant gaps between the patenting and introduction of new appliances—including the electric iron ( 1903), the vacuum cleaner (1907), the toaster (1909), the electric stove (1912), the refrigerator (1913)—and their widespread ownership. Radio was adopted the fastest of all: 75 percent of households had it by 1937.

The same dominant share was reached by refrigerators and stoves only in the 1940s—dishwashers by 1975, color TVs by 1977, and microwave ovens by 1988. Again, as expected, these diffusions followed more or less orderly S-curves.

Rising ownership of these and a range of other heavy electricity users drove the share of residential consumption to 25 percent by the late 1960s, and to about 40 percent in 2020. This share is well above Germany’s 26 percent and far above China’s roughly 15 percent. A new market for electricity is opening up, but slowly: So far, Americans have been reluctant buyers of electric vehicles, and, notoriously, they have long spurned building a network of high-speed electric trains, which every other affluent country has done.

This article appears in the June 2022 print issue as “Electricity’s Slow Rollout.”

Vaclav Smil writes Numbers Don’t Lie, IEEE Spectrum's column devoted to the quantitative analysis of the material world. Smil does interdisciplinary research focused primarily on energy, technical innovation, environmental and population change, food and nutrition, and on historical aspects of these developments. He has published 40 books and nearly 500 papers on these topics. He is a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (Science Academy). In 2010 he was named by Foreign Policy as one of the top 100 global thinkers, in 2013 he was appointed as a Member of the Order of Canada, and in 2015 he received an OPEC Award for research on energy. He has also worked as a consultant for many U.S., EU and international institutions, has been an invited speaker in more than 400 conferences and workshops and has lectured at many universities in North America, Europe, and Asia (particularly in Japan).