A Pick Up for the Electric Vehicle Market

Electrifying light-duty trucks will lower the cost of the electric vehicle transition, according to new research.

In the early 2000s, the Hummer became a symbol of cars at their environmental worst. One of these gas guzzlers consumed as much fuel per mile as five Toyota Priuses. The surge in sales of light-duty trucks, especially SUVs, throughout the 1990s was seen as a scheme to avoid the more stringent fuel economy standards applied to cars. Consumers loved these vehicles, but advocates for cleaner air and a cooler climate did not.

But new research now shows that it may be time for environmentalists to embrace trucks and their siblings. Cutting US transportation emissions without them will be tough.

Policy leaders in the US are starting to put very aggressive climate goals on the table that will require widespread electrification of transportation within the next 30 years. President Biden wants net zero emissions economy-wide by no later than 2050. California Governor Newsom has declared that all sales of light-duty vehicles (generally consumer vehicles such as sedans, crossovers, light trucks, vans) shall be zero emissions vehicles by 2035.

Recent national and state studies show ways these aggressive goals could be met. These studies describe what’s possible, but they can leave policy makers scratching their heads about how to turn the scenarios into reality. In 2019, 17 million new light-duty vehicles were purchased in the US. While regulations help shape this market—you can’t choose to buy a car that burns leaded gasoline or lacks a seatbelt— consumers still have many choices.

Rebates for new electric vehicle purchases are one popular tool available to policymakers. Research by Erich Muehlegger and David Rapson, summarized by Max Auffhammer here, shows that rebates have been a very effective way to boost demand for electric vehicles. However, relying on rebates alone is very expensive. Severin Borenstein and Lucas Davis have shown that electric vehicle rebates are also very regressive.

Now a new study by Muehlegger and Rapson, plus James Archsmith, shines light on factors that may be even more important than rebates.

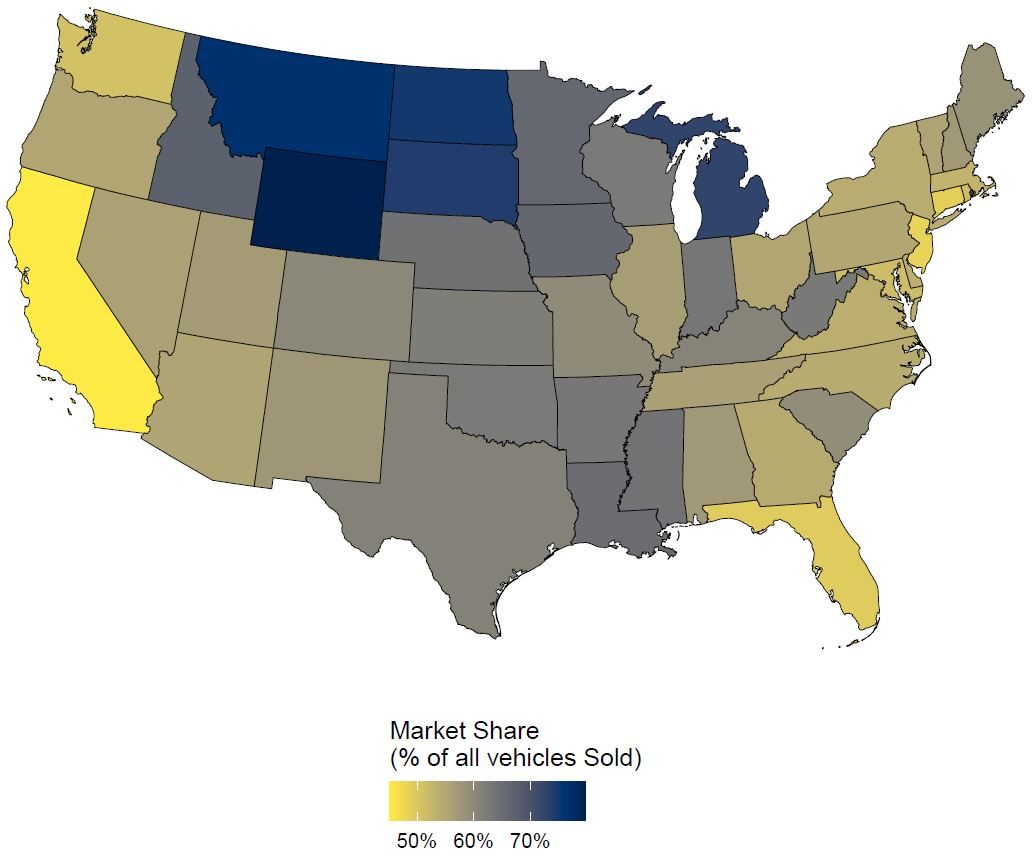

Big Regional Differences

The authors draw on a survey of over 200,000 new vehicle buyers, conducted annually by a third-party firm. The surveys provide insights on the purchase decisions and demographic information about the buyers. The authors use this data to develop a model that estimates the likelihood that a consumer would buy an electric vehicle. The survey data illustrate how dramatically the popularity of different vehicle types varies across the country. Anyone enjoying a post-COVID, cross-country vacation will observe this. Sedans are popular in California and in the northeast, but trucks, including SUVs and pickups, dominate everywhere else. Their model accounts for these differences.

They also highlight a disconnect in today’s electric vehicle market. Most buyers want trucks, but most electric vehicle models are sedans. Whether and how this disconnect is resolved proves to be a critical factor in their model.

Archsmith, Muehlegger and Rapson use their model to estimate the aggregate amount of rebates necessary to hit different market share goals by 2035 — 20%, 35%, 50%.

Intuitively, the model finds that when a consumer is on the fence about buying an electric vehicle, a relatively small rebate can nudge them to do so. But rebates need to be really high to convince someone to buy a vehicle they do not want. Would someone who really likes full-size pick-up trucks instead drive a small, Chevy Bolt even if it were free?

The authors consider how interest in electric vehicles might increase as technology improves and charging infrastructure is expanded. Then they estimate how the amount of rebates could change. They find that if interest grows quickly, then rebates to encourage electric vehicle purchases might not be required at all. But in other plausible scenarios, trillions of dollars of rebates would be necessary to achieve a 35 percent market share for electric vehicles by 2035.

Transformative Trucks

A point that Archsmith and coauthors make strongly is that the US vehicle market needs electric light-duty trucks. Their model shows that the strong preference that many consumers have for trucks means that the availability of attractive, cost competitive electric trucks could double the market share of electric vehicles over the next 15 years.

Full-size electric pickup trucks and SUVs are arriving in the next 18 months — the Tesla Cybertruck, Rivian R1T, Ford F-150, and, yes, the electric GMC Hummer. This new study suggests that these vehicles could be game-changers.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Campbell, Andrew. “A Pick Up for the Electric Vehicle Market” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, July 19, 2021, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2021/07/19/a-pick-up-for-the-electric-vehicle-market/

Categories

Andrew G Campbell View All

Andrew Campbell is the Executive Director of the Energy Institute at Haas at the University of California, Berkeley. At the Energy Institute, Campbell serves as a bridge between the research community, and business and policy leaders on energy economics and policy.

With my SUV/trucks I tow boats into saltwater and fresh lakes. There had better be some serious testing of batteries being able to sustain some nominal submersion like combustion vehicles if I were to not reflexively reject the idea of a EV-SUV or EV-Truck.

While I agree with the premise, the prospect of a bunch of 563 HP (775 lb-ft of torque) F150 pickups driving 90 MPH (or more) on our Southern California freeways is a little scary. There are enough crazy pickup drivers around here already who seem to think they own the roads, and feel free to intimidate anybody who dares get in their way.

EV pickups with spectacular features are about to be offered. These EVs may be a game changer for a different reason than what those focused on transportation policy think of–they offer households the opportunity for near complete energy independence. These pick ups have both enough storage capacity to power a house for several days and are designed to supply power to many other uses, not just driving. Combined with solar panels installed both at home and in business lots, the trucks can carry energy back and forth between locations. This has an added benefit of increasing reliability (local distribution outages are 15 times more likely than system levels ones) and resilience in the face of increasing extreme events.

The difference between these EVs and the current models is akin to the difference between flip phones and smart phones. One is a single function device and the we use the latter to manage our lives. Of course the smart phone exploded from a 30% share in 2011 to beyond 85% now. The marketing of EVs should shift course to emphasize these added benefits that are not possible with a conventional vehicle. The barriers are not technological, but only regulatory (from battery warranties and utility interconnection rules).

https://www.ford.com/trucks/f150/f150-lightning/2022/

https://www.gmc.com/electric/hummer-ev

https://plants.gm.com/media/us/en/gm/ev.detail.html/content/Pages/news/us/en/2021/apr/0406-factory0.html

You don’t need a large truck to gain significant storage capacity. My Kona EV has a 64 kWh battery, which is over 3x the capacity of the Sonnen Ecolinx 20 currently used in my home microgrid. I could run my home off the grid, if needed, with PV and the 20 kWh battery though I would probably have to minimize usage of some electric appliances. The main things holding this back are controls and infrastructure to support V2G, not battery size.

Low energy-dense batteries should actually be used in cars as lightweight as possible. Vehicle mass not displaced = kWh not needed. There is a reason why Tesla’s popular Model 3 has a 1100 lb weighing battery pack on board, approx. 5-6 times as much as the usual single occupant, the driver. For trucks and SUVs it is even worse. The huge problem is that with rising temperatures because of Global Warming, we’ll have way more AC units AND cars dependent on the grid. The EV is to become a household’s Nr. 1 energy consumer. Major investments in strained power grids are required.