What’s the Matter With Gasoline Prices?

Political rhetoric from both sides is more distracting than enlightening.

Being an energy economist isn’t as glamorous as it looks. As with any expertise, it takes thousands of hours to hone our skills. A lot of that time goes into repeating, “gasoline prices are up because world oil prices have increased.” It’s not too late to join the fun, but you’d better start practicing now. No need to polish the opposite phrase, “gasoline prices are down because world oil prices have declined.” You won’t be asked about gas prices during those times.

Another skill you must polish is diplomatically responding to people who insist that gas prices only go up, never down. Then there’s practicing adjusting for inflation, and learning the difference between producing oil and refining it into things like gasoline and diesel. The grind is seemingly endless.

I have been putting all my training to work over the last few months as politicians and the media have been obsessed with “doing something” about high gasoline prices.

Confusion to the left of us

On the Left, leaders express outrage that oil companies are making so much money and not sharing it with consumers by lowering gas prices. Like that’s a thing. Apple is going to lower its iPhone price because it’s making too much money? Facebook is going to, uh, sell only half your personal information, because its profits have too many zeros?

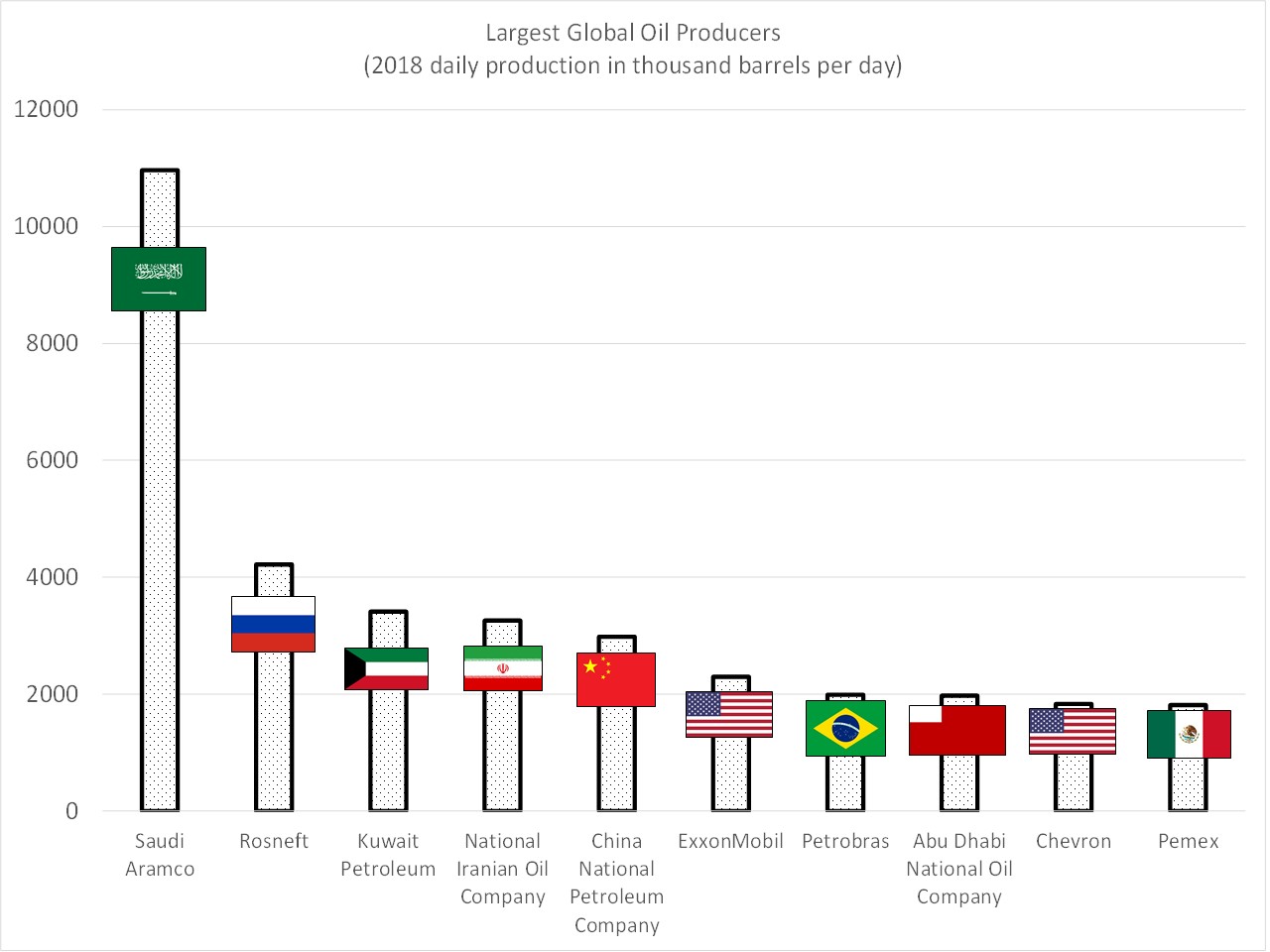

Some suggest the oil market needs more competition, and they are right. The world’s largest oil seller, Saudi Arabia, props up prices by limiting its output. We respond by looking away from their human rights abuses and government-sponsored murder, so we can ask these “friends” to make up for the supply shortfall resulting from (finally) sanctioning Russia. Seems like we are just digging one hole deeper to fill up another.

Instead, some politicians call U.S. oil producers on the carpet. The companies explain that prices are set in a world oil market, in which they are each small players, so they can’t do much about the price of oil. (Another phrase we chant during our energy economist training: “It’s a world oil market”). Just like homeowners in a skyrocketing housing market, their huge profits are due to luck, not any actions they have taken.

That’s what the execs say out of one side of their mouth. The other side is saying things like producing less oil in California increases California gasoline prices. (If it’s not obvious why that doesn’t make sense, please return to the top of this post and start over.)

Some Democrats are floating a windfall profits tax to capture a share of Big Oil’s lucky crude profits and use them to help families hit by high energy costs and inflation. The idea makes most energy economists queasy because defining windfall profits is notoriously difficult. The oil industry says that targeting new taxes based on an industry’s profits risks undermining investment incentives.

At first, that sounds reasonable, but then we remember back to the spring of 2020. That’s when industry executives said that low prices indicated the market was dysfunctional and needed government assistance, everything from asking Texas to coordinate production cuts across firms (known as collusion), to getting Trump to pressure other countries to reduce output (also known as collusion), to receiving billions of dollars in government subsidies. The bedrock principles of capitalism didn’t seem quite so compelling to oil industry execs back then. Perhaps the middle ground is having oil companies pay back those subsidies, and then we can talk about their sporadic belief in limited government.

Confusion to the right

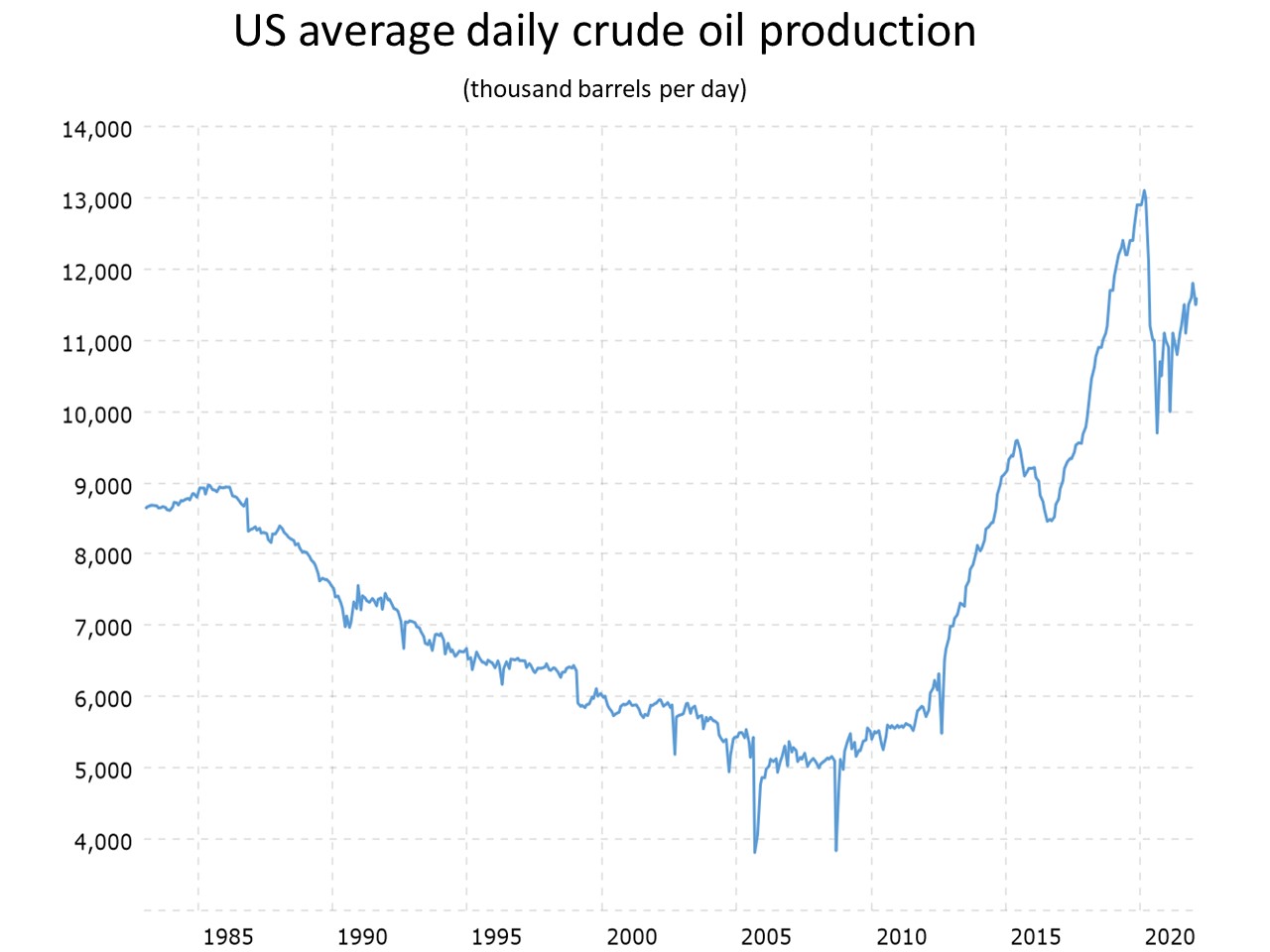

From politicians on the Right comes the “drill, baby, drill” policy response. If we just open up more land to oil production, gas will be cheap again. The true part of this assertion is that increasing aggregate U.S. oil production would push down oil prices somewhat, as has happened over the last decade from the fracking revolution.

But U.S. crude production is still more than 1 million barrels per day below pre-pandemic levels, and that’s with strong drilling incentives from $100 per barrel oil prices. The slow return of post-pandemic production is due to shortages of equipment and labor, not restrictions on government leasing. Plus, leases auctioned off today wouldn’t start producing oil for years. Making more land available for oil production is the opposite of good policy: it would do nothing in the short run and would increase supply in the long run, when we really need to be cutting fossil fuel consumption.

A Uniquely California Mystery

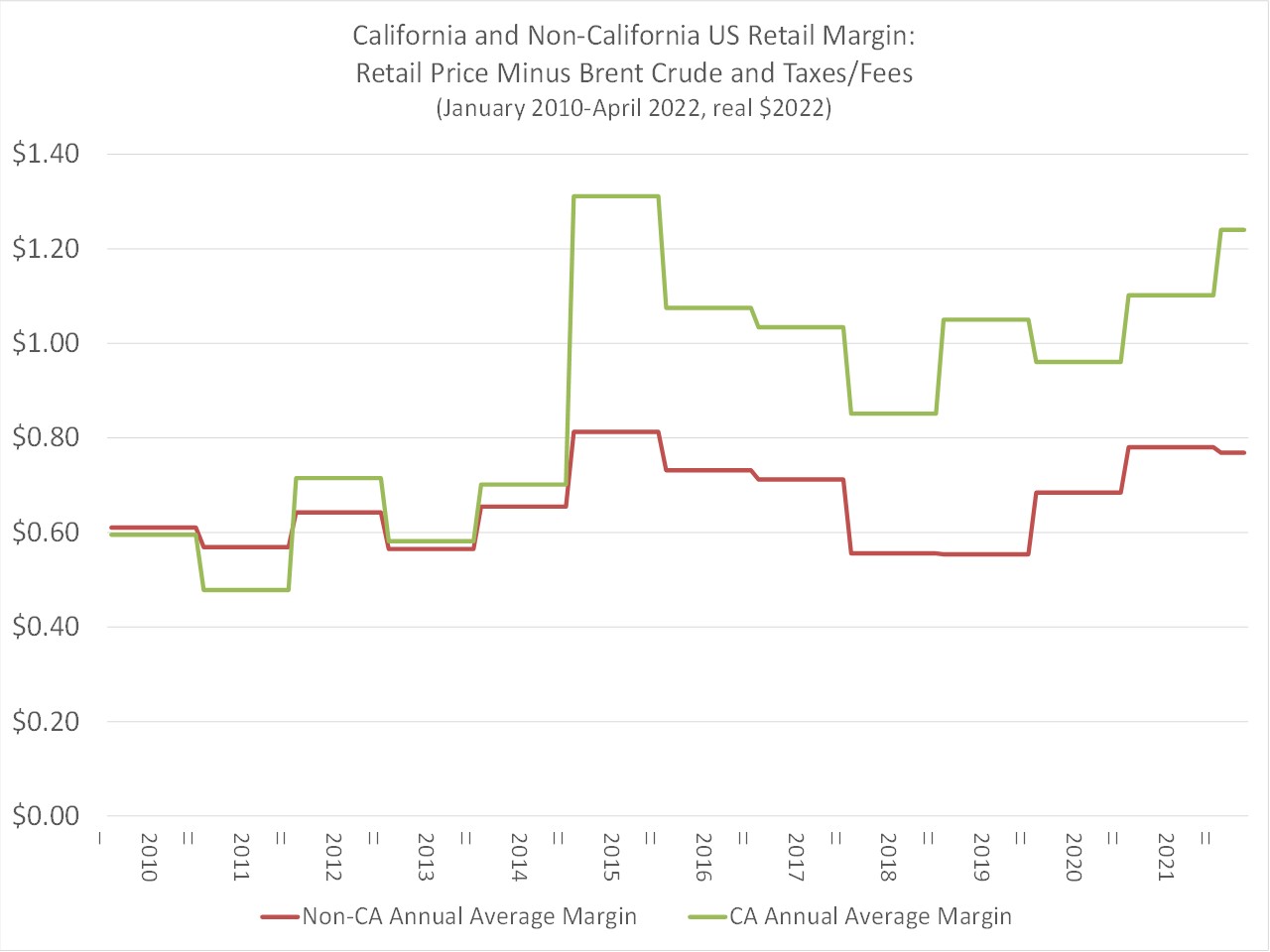

If there is not much we can do about the oil market, maybe we should look downstream, at gasoline refining, distribution, and retailing. Outside of California, however, it’s hard to pin much on these sectors. The downstream margins wax and wane – higher when crude prices fall and retail prices lag behind, lower when crude rises and retail increases less quickly – but it’s hard to see much trend in the average gap between retail gasoline and crude oil prices.

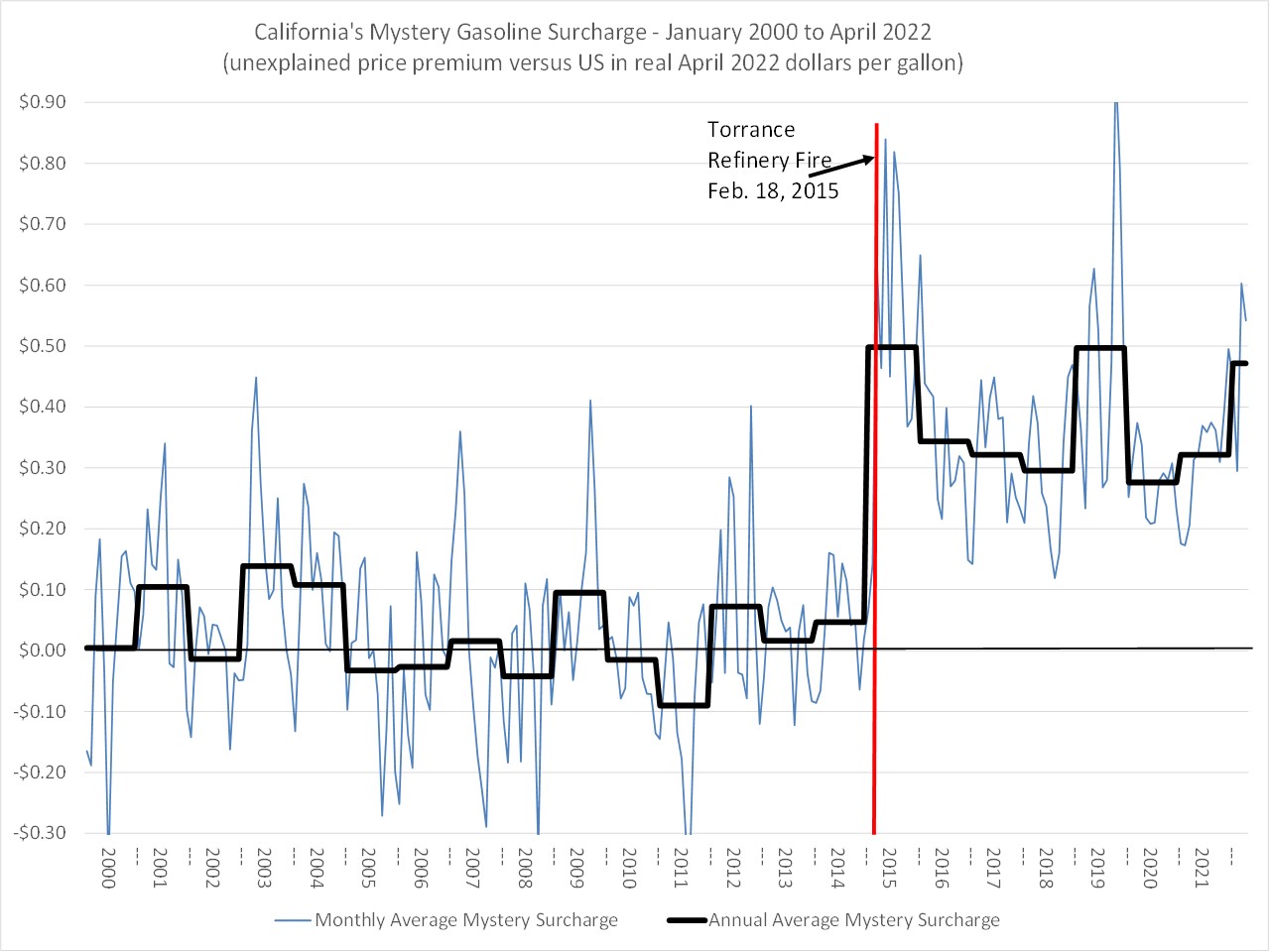

The story is different, however, here in the Golden State. There’s lots of trouble to talk about downstream, but still not many people in Sacramento who want to talk about it. The Mystery Gasoline Surcharge that started in 2015 – the unexplained difference between California retail gasoline prices and the rest of the country, after adjusting for taxes and environmental fees – is off to a roaring start in 2022. It looks to be even more impressive than 2021, when California drivers saw about $4 billion disappear down this mysterious drain, with most of it almost certainly going into the downstream firms.

It’s frustrating when straightforward economic analysis takes a backseat to political rhetoric and ideology. But from the day you’re awarded your energy economist beanie, your job is to shine a light on energy markets, whether they are working well or poorly. Besides, it beats chanting “gasoline prices are up because world oil prices have increased.”

Find me @BorensteinS most days tweeting energy news/research/blogs.

Keep up with Energy Institute blog posts, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Borenstein, Severin. “What’s the Matter With Gasoline Prices?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, May 2, 2022, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/05/02/whats-the-matter-with-gasoline-prices/

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

Being an energy economist is glamorous? I have to tell my wife; I don’t think she realizes that her husband has a glamorous job!

Thanks, a nice article. Some of us are also old enough to remember the last “windfall profits” tax from the Carter administration. The worst part wasn’t the tax payments but figuring out the various prices and requirements for “old” oil, “new” oil, “stripper” oil, etc. At least it was simpler than the Natural Gas Policy Act, which established 20-something separate prices for natural gas. On the flip side, while market collusion is generally bad, one could argue that the IOCC market collusion from the 1930’s-60’s was probably a good thing for the U.S.

The frustrating thing with the situation today in Ukraine is that many policymakers still don’t understand the basics of the oil market. Banning the purchase of Russian oil is an understandible sentiment, but even the threat of doing so drives up global prices and Russian revenues. The EU should instead allow member states to import Russian crude, but require them to deposit $30 for every barrel imported into a war reparations fund for Ukraine. The EU has enough market power to force Russia to pay almost all of this de facto tariff, and signaling that Russian barrels will remain on global markets would lower global prices, as well. It would also establish a mechanism for the invader to begin to pay for some of the damages it has caused.

Would seem to me that gasoline etc suppliers are as much a ‘utility’ as electricity, gas, water, etc. So – that SHOULD also be regulated as a ‘utility’. With prices set by an ‘agency’ more dependable than the PUC. ALL outlets, refineries, etc owned and operated by the state regulated ‘utility companies’.

Nice analysis.

Well done, Severin!

A well crafted post; the tongue-in-cheek humor is effective.