Rationalizing Compensation for Rooftop Generation

Proposed CPUC decision remains cold-eyed about sweet deal solar households are getting.

Once again, Californians are battling over how to compensate and incentivize rooftop solar. Last month’s California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) proposed decision (PD) replaces a quickly withdrawn PD from 2021. The 2021 PD would have reduced the compensation for exporting power to the grid — which is typically nearly half of a system’s output — and imposed a monthly grid-usage charge on solar households averaging about $50 per month. The new PD eliminates the monthly charge and slows the decline in export compensation. Existing solar homes are exempted from any change.

Compared to the CPUC’s 2021 proposal, this is a big shift in favor of rooftop solar. But the PD’s reasoning remains cold-eyed about the sweet deal solar households are getting. The new PD recognizes that solar customers receive compensation many times higher than the value they deliver to the grid, that this excess compensation causes a large cost shift onto households without solar, and that those solar-less residents are disproportionately poorer than solar adopters. Yes, some lucky low-income households benefit from targeted solar incentives, but the vast majority won’t have solar for a decade, if ever. So their rates will pay for all of the solar subsidies, a kind of solar rooftop Hunger Games.

(Source)

The cost-shift conclusion is supported by the analyses of the utilities, which the rooftop solar advocates argue shows is just big-utility driving the regulatory bus. But it is also supported by analyses from the CPUC, the CPUC’s independent Public Advocate Office and The Utility Reform Network (TURN) — both of which disagree with the utilities on pretty much everything else — as well as the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the leading environmental groups, and our own analysis at the Energy Institute at Haas.

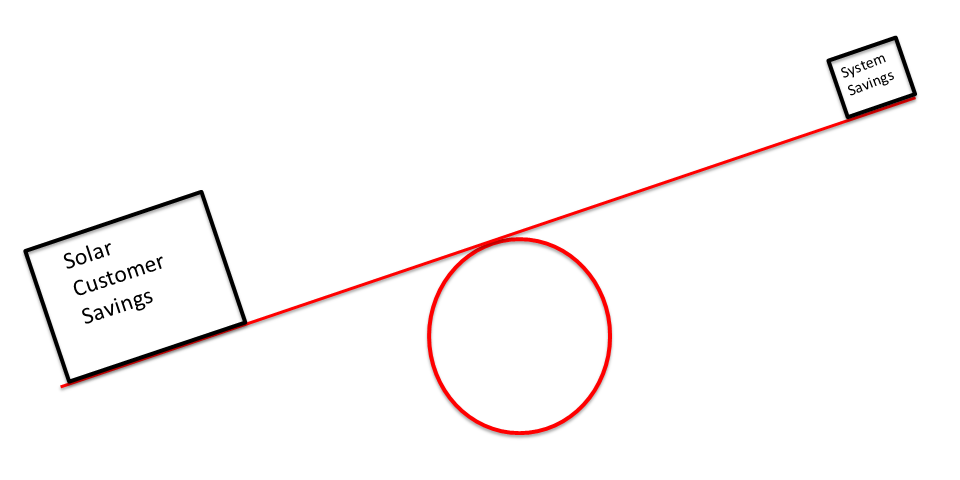

It’s difficult to reach any other conclusion. A kilowatt-hour from rooftop solar reduces system cost by about 10 cents (most analyses) to 15 cents (analyses by rooftop solar advocates) while lowering that customer’s bill by 25-50 cents. That gap between what the solar customer saves and what the system saves is due to the large share of the price that pays for fixed costs that don’t decline when a customer generates power, including grid infrastructure and hardening, vegetation management, energy efficiency programs and technology R&D. That extra savings to the solar customer is covered by raising rates for everyone else.

The low system savings may seem surprising. Besides reducing fuel costs at power plants, solar advocates point to billions of dollars that rooftop solar saves in transmission lines. But those billions will be saved over many decades, so it works out to less than a penny per kilowatt-hour. They point to cases where it delays upgrades to local distribution lines, but the best research shows that it only really helps on a tiny percentage of those lines. They argue it reduces pollution, but California is now awash in renewables in the middle of the day when solar is producing.

The low system savings may seem surprising. Besides reducing fuel costs at power plants, solar advocates point to billions of dollars that rooftop solar saves in transmission lines. But those billions will be saved over many decades, so it works out to less than a penny per kilowatt-hour. They point to cases where it delays upgrades to local distribution lines, but the best research shows that it only really helps on a tiny percentage of those lines. They argue it reduces pollution, but California is now awash in renewables in the middle of the day when solar is producing.

So, if it hasn’t changed its analysis, why is the CPUC changing its proposal? One sentence in a 2014 law — a sentence almost no one noticed when it was signed — says rooftop solar policy must assure that the industry will “grow sustainably.” Basically, the PD says the new rates will still create a regressive cost shift, but the law leaves the CPUC no choice. There’s no such law for other renewable options — such as wind power, grid-scale solar, and geothermal — all of which are drastically less expensive than rooftop solar. The state is simply putting its thumb on the scale for solar on buildings.

(Source)

This is not the David versus Goliath fight the advocates claim. The utilities may have once been dominant, but Tesla, SunRun and the other rooftop solar companies are the ones flexing their legislative/regulatory muscle now, even over vehement objections from the leading consumer-protection groups.

California is among the first movers on renewable energy, and the whole world is watching. If we do it right, we can show the pathway to equitable and cost-effective decarbonization. If we make it into an expensive mess, other states and countries will wonder if they can afford to follow. California’s rooftop solar bias is pointing us in the wrong direction.

This post ran as an op-ed in the San Jose Mercury News and East Bay Times on December 12, 2022.

Free of Twitter, I post most days on Mastodon @severinborenstein@econtwitter.net

Keep up with Energy Institute blog posts, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Borenstein, Severin, “Rationalizing Compensation for Rooftop Generation”, Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, December 14, 2022, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/12/14/rationalizing-returns-to-rooftop-generation/

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

Facts can be painful sometimes. The reality is that utility-scale solar is less than 1/4 of rooftop solar costs. If we want more green power, why should pay for the expensive stuff when it is the same as the cheap stuff? The reality is that we need more flexible storage. Why should subsidize and fund rooftop solar instead of battery power? The reality is the grid is a lot like our road systems, they are based on large-scale infrastructure investments that last for decades, most of which are sunk costs. The limited grid costs that can be avoided are related to grid expansions, if, and only if, the peaks coincide with when solar peaks, which they do not. The reality is that if you have rooftop solar, you use the grid – a lot. When rooftop solar exports excess power, it uses the grid. When that home imports power in the evening it uses the grid. In fact, most homes with rooftop solar use the grid more than homes without it. If you use the grid, shouldn’t you have to help pay for it? The reality is that for years ratepayers have been paying rooftop solar owners to use the grid – when solar customers should have been paying for the grid. It was hidden and very large subsidy, neatly tucked away in rates – but everyone who payed attention knew it was there. Since when do FedEx or UPS – both delivery companies – have to pay me to deliver my packages? The reality is that the subsidy should have been in the open with a schedule for phase-out. Instead it, it became entangled, which makes it that much harder and painful to rip it out, but the right move is to rip it out.

From a responsible solar owner (one that always paired it with storage)

So many questions left unasked. Here are a few questions running through my head as I read this … I struggle for the word … “editorial”:

Are there other cost shifts with more dramatic impacts today and in the foreseeable future?

I’m consistently surprised by the selective attention placed on the cost shifts that are inconvenient to the obvious imperatives of the utility industry today. Other economists (hello, Ahmad) can speak to the range of cost shifts endemic in the industry far better than I can, but if one were to stack rank the impact of cost shifts (like the fact that my non-air conditioned home is subsidizing the disproportionate costs of hot days) where would solar fall? I struggle to think it would be at the top of the list measured either in dollars or equity.

Are there other voices beyond NRDC in the environmental community?

In fact, NRDC continues to be an outlier in this debate. Perhaps it is because they are the only ones with clear sight while all the other environmental groups wear bifocals.

Is there any benefit to having private investment flowing into solar and distributed energy?

Seems that I’ve read economists like the idea that those with the best local knowledge are the ones best positioned to determine the value of their investments. Wouldn’t this help reduce the increased debt forced onto all ratepayer through an ever-increasing rate base. Does the fact that private, not ratepayer, capital is being deployed factor into the 15¢ or 50¢?

Is there a value to resilience?

The “low-cost” clean resources are fantastic and we should have more, but they do little good when there’s a fault in the network, which is all too common with our brittle system today that is vulnerable to storms, trees, firearms and squirrels. Solar alone doesn’t solve the resilience equation, certainly one of the key components. If the policy is going to drive more microgrids, as Richard suggests, then I’m all for it, but it seems like that’s akin to praising the British Empire for creating so many Independence Day celebrations around the world in its decline.

Are there any perspectives from outside the regulatory institutions worth considering? Is it possible that those on the inside of the process may be a bit close to the process?

Is there any evidence of low-income and disadvantaged communities supporting solar?

Like NRDC, seems to me that TURN may be the outlier in this respect.

Finally, I’ll just say that the assertion that the solar industry has some political advantage over the utility industry is laughable on its face. Somewhere in that 50¢ of cost are teams of lobbyists, regulatory staff, outside counsel and consultants that are all costs borne by ratepayers that are orders of magnitude greater than what the distributed energy industry can bring as a whole. I’d call that a pretty “sweet deal”. Suggesting otherwise is either willfully ignorant or intentionally misleading. I’ll give the benefit of the doubt that it’s the former, because the latter feels too cynical even for me on this evening.

I know there’s little point to this post since most people (myself included, I’m sure) ain’t gonna learn what they don’t want to know, but, man, I would sure welcome a bit less smugness than to suggest that “it’s difficult to reach any other conclusion” that the one that Mr. Borenstein reaches only by limiting the scope of his analyst so dramatically.

Then again, it wasn’t the buggy makers that built cars and I haven’t seen any auto manufacturers making e-bikes.

Cameron, consider this very simple high level fact; numbers I quote are approximate but reasonable. In the last ten years or so, the following has happened:

* PV manufacturing prices have decreased by a factor of two. Accordingly RPS contracts are now just 2-3 cents/ kWh

* California has installed many more GW of solar, so it is appropriate that the marginal value of solar to the grid isn’t as high as it used to be.

* Retail rates, at which we credit rooftop solar, have increased by a factor of two. NEM customers likely avoid paying a weighted average of 20+ cents per kWh for electricity generated by their rooftop solar.

* Rates will go up a little for everyone next year again because of inflation, spending on grid hardening and undergrounding, and wholesale gas price increases. This means credits for NEM will increase as well.

What’s wrong with that picture?

Mohit

First, we should be asking why have rates gone up by a factor of two? Any rate burdens from NEM customers is less than 20% of that 100% increase–what are the other factors attributable to those increases and who should be bearing the burden of those? It’s that increase that makes rooftop solar look like a bad deal now.

Second, rates are not going up “a little” for everyone–PG&E is projecting a nearly 30% increase by 2026, again none of it attributable to rooftop solar. What’s wrong with this picture?

Richard,

Two, of many, very real and disturbing trends that need to be addressed: (1) the rapid increase in revenue requirement in PG&E territory and (2) the NEM cost-shifts that distort the distribution of revenue requirement amongst PG&E residential customers. The existence of one problem does not obviate the need for dealing with the other problem. The CPUC opened a proceeding on net metering and we dealt with that. With some success. With rate reform through the new demand flex proceeding we’ll have made a sizeable dent in the problem of how approved revenue is allocated amongst customers. I’m fairly confident.

The rapid increase in revenue requirement is an ongoing problem to solve via right sizing utility investment, funding social policy from outside the electric sector, and other TBD levers. Looking forward to hearing more from the community on how to deal with this problem.

Mohit

There are three cost shifts that have generally been “huge” relative to any cost shift associated with solar.

The first is multi-family customers subsidizing single-family customers. Distribution services are dramatically cheaper to multi-family dwellings, with many customers sharing a service drop, and the utility essentially providing only primary voltage service plus a transformer bank. One wire connects to the building, with the building owner providing all of the distribution secondaries. The building I am staying in today is an example: 84 apartments with a single grid connection. Nevada charges multi-family customers about 10% less than single-family, but most utilities, including those in California charge the same rates. California offset this for many years with a zero customer charge and an inclining block rate, but both of those are soon to be history, so California will join the rest of the industry, forcing renters to subsidize homeowners.

The second is urban customers subsidizing rural customers. A few utilities have separate rate schedules for “in-town” customers versus rural customers, but very few. Urban customers can be 1000 connections per circuit-mile, suburban customers more like 100, and rural customers as few as five. The distribution costs are much higher per-customer or per-kilowatt-hour for rural customers, but on most utilities, they pay the same rates. Once again, mostly renter urban customers are subsidizing mostly homeowner rural customers.

A third is overhead service customers subsidizing underground service customers. A few utilities charge a premium for more-expensive (and less ugly, and more reliable) underground service, but not many. Older neighborhoods are often served with legacy overhead services, while newer suburbs, built after 1980 or so, were required to be served with underground.

Ahmad has raised the issue of customers who have invested (their money or utility money) in energy efficiency receiving a subsidy, while I prefer to think that these customers have freed up capacity on the existing distribution grid to be able to serve EVs, electrification of heating loads, and other services, thus helping to avoid expensive distrib ution upgrades. My house is an example: an energy-star fridge and freezer, energy-star dishwasher and laundry mean that my house, with an EV and an electric hot tub, uses about the same amount of power as it did 30 years ago with the previous owner.

Smart Rate Design for a Smart Future https://www.raponline.org/knowledge-center/smart-rate-design-for-a-smart-future/addresses how these subsidies can be reduced, and a few utilities have done so.

Both Burbank Water and Power (California) and Snohomish PUD (Washington) have adopted graduated monthly fixed charges, depending on the size of the service connection. The Hawaii PUC has just directed this change in Hawaii, scheduled to roll out in July of 2023. This ensures that all customers, regardless of usage, pay for the full cost of their connection to the grid, but without overcharging apartments or undercharging mansions.

If solar customers pay the full cost of their connection to the grid in a monthly fixed charge, as the new Proposed Decision requires, pay for the power and grid services they use in a TOU rate, and are credited for backfeed on the basis of the value of the renewable energy they deliver into the distribution system, subsidies to solar customers are eliminated.

In Hawaii and California, with high solar saturation, the solar cost shifts may approach the other cost shifts in magnitude. For most of the country, however, the urban/rural and multi-family/single-family cost shifts will remain much more dominant.

This post confuses cost-shifts with intentional cross-subsidies.

Cost-shifts occur when a customer’s private actions to maximize their own utility, or benefit, unintentionally results in an inequitable increase in costs for other customers within the same rate class. Well-designed rates based on cost causation principles will help minimize this phenomenon and instead align the private incentives of customers with actions that are most beneficial for the electric grid and to achieve state climate policy goals.

Cross-subsidies are intentional policy actions, such as low-income discounts including CARE and FERA, in alternate rates to achieve specific policy outcomes, such as equity. This isn’t to say that existing cross subsidies are appropriate for now and in the future; some of these will be reviewed through the new CPUC demand flexibility and rates proceeding.

Going back to cross subsidies, there is significant confusion in the electricity and advocacy community on what costs to serve a customer are marginal versus fixed. We hope to work through this confusion and develop rates that better reflect cost causation; also through that same CPUC proceeding.

Thanks for sharing that paper; I’ll read through it.

Interestingly enough, NEM 1.0 began as an intentional cross subsidy–there was not an illusion that it would pay for itself. Except along came the IOU’s RPS auctions in the 2008-2012 period, and those contract prices plus transmission approached the apparent avoided retail rates paid by NEM customers! NEM 2.0 was intended to correct the retail rate relationship in the context of 2016 retail rates, but the cost controls really came unleashed and IOU rates have skyrocketed since then, almost entirely due to their own management decisions.

The only other intentional cross subsidy are the CARE/FERA income supports, which amount to a bit more than a penny a kWh. All of the other cost shifts that Jim Lazar lists are intentionally or unintentionally overlooked by the CPUC (they’ve all been identified by various groups.)

In 2007, I first inquired about interconnecting to the grid with a small home-built system with PG&E and it was too small to get approval from the utility, so I just took it off-grid and used batteries. Over the years the system has grown to 8,000 watts of solar panels with 56 Kilo watt hours of deep cycle lead acid batteries and power’s part my home day and night. Today, an off-grid system is called a back-up system when grid connected and is commonplace with all the major solar installers. These systems do not need to grid connect and basically power the home without a utility getting involved or paid. Thanks to Hawaii and Nevada, solar installers learned to bypass the utility to keep their sales going. Just like my system was built without the utility, anyone wanting to reduce their bills and go green will be able to do so no matter what the CPUC decides.

There is no rule that keeps one from powering their own home with batteries as long as the homeowner is willing to pay for those batteries and their replacement batteries at the end of life. The IRA act allows for a federal tax credit for any system built for the primary home, including the batteries, even if not connected to the grid. The ongoing cost for batteries is about $100.00 per month pro-rated and if one’s current utility bill for electricity is over $200.00 per month, going off grid could be the answer for future rooftop solar in California. Unless there is a drastic cut in the electrical tariffs charged by the California utilities, there will be defectors to the cheaper alternative of off-grid systems.

Any claims of benefits of energy systems have to be evaluated by their real cost per tonne of carbon reduction. As with much of the debate on renewable energy, rooftop solar advocates are failing to note the real cost. California should take a lead on evaluating any low carbon claims by the cost per tonne of carbon reduction and the reliability of supply. Try to run a household on just rooftop solar and it is immediately obvious that the cost of enough solar panels to supply power in winter plus battery power for day to day fluctuations would be many times that of the solar panels now most households have installed. This price increase is equivalent to the subsidy that is currently being provided.

There is the lingering question of why the cost of distribution for PG&E is so high. I know someone in Washington state who pays a flat fee of $31/month to be connected to the grid, then close to generation costs of just $0.06 to $0.08/ kwh. I would have thought that the distribution cost would have not been significantly different between Washington state and California.

*There are good arguments for crediting NEM exports at rates below the retail price of energy [and I personally support that], but any argument that claims that retail credit is a “cost” is simply false.

If a NEM customer exports more than can be offset in credit, that’s a different matter, and those “excess generation” payments are already paid at the wholesale rate, not the retail rate. Payments and credits are not the same thing.

This article once again falsely compares apples to oranges when it looks at the wholesale price of energy or “avoided cost” against the credit given to a NEM customer. The IOU is not buying energy from a NEM customer, they are instead taking energy from a NEM customer, selling it to their neighbor, and crediting the NEM customer the same amount. If I give you an orange and you sell it for a dollar and give me that dollar, that does not cost you anything, and the person receiving the orange is paying the standard price for it, no more or less. [Yes, there is a de minimis cost to execute the transaction, but that’s not the issue]

This “opinion” piece reflects poorly on the Energy Institute.

Sahm: Can you please reconcile your assertion, copied immediately below, with Severin’s copied after that. Maybe it’s just me, but I’m having trouble following your assertion and orange transaction analogy.

“The IOU is not buying energy from a NEM customer, they are instead taking energy from a NEM customer, selling it to their neighbor, and crediting the NEM customer the same amount. If I give you an orange and you sell it for a dollar and give me that dollar, that does not cost you anything, and the person receiving the orange is paying the standard price for it, no more or less.”

Severin: “A kilowatt-hour from rooftop solar reduces system cost by about 10 cents (most analyses) to 15 cents (analyses by rooftop solar advocates) while lowering that customer’s bill by 25-50 cents.”

Thank you, Professor Borenstein for your thoughtful and direct blog posting. New England (I work and reside in Massachusetts) appears to be following in California’s footsteps on this particular issue. Since rooftop solar is behind-the-meter and subject to state regulation, I suspect that there is little the CAISO can say or do to address the inefficiencies and cost-shifting issues resulting from California legislation. However, such state policies have the result of significantly increasing energy injections from rooftop systems, which in aggregate could eventually cause operational (and ultimately economic) issues on the regional power system starting in low-load seasons.

That is, if production from roof-top systems combined with other non-dispatchable power sources (grid-connected solar, wind, run-of-the-river hydro, nuclear) exceeds load, system voltage would be impacted, which could damage customer equipment as well as elements of the power system itself. I would imagine that the CAISO is beginning to experience over-generation issues in the spring and perhaps late-autumn seasons. Since the CAISO probably does not model, does not have visibility into, and cannot exercise operational control over resources located in distribution systems, how would such issues be addressed especially as more variable, renewable generation becomes a bigger proportion of the generation fleet as we pursue de-carbonization?

Are the distribution utilities in California exercising any dispatch control over the generation resources located on their systems so that physical problems from over-generation are not exported to others through the regional power system? If so, are these operations being coordinated with CAISO? Perhaps storage and demand flexibility (i.e., increasing load during periods of excess generation) would help here, but that requires dispatching storage load and demand to increase in real-time to match the over-generation on a time and location-specific basis. Is California or the CAISO looking into dispatching demand in both the upwards and downward directions to address increasingly inflexible supply?

Any insights you could provide on the above would be appreciated. Again, many thanks for your thoughtful comments.

Mr. Yoshimura – At the risk of speaking on Dr. Borenstein’s behalf, I can share the approaches being investigated by senior (4th year) Power Engineering students at Sacramento State University. Prediction of rooftop solar (RTS) contribution has been investigated for multiple years within an area of PG&E’s grid where adoption exceeds 20% and has resulted in Python algorithms that predict “behind the customer meter” RTS generation within a +/- 2% accuracy. This algorithm allows additional “planning margin” over system load to cover the shortfall following line outages when RTS shuts down. More recent investigation includes sizing of substation sited battery energy storage systems (BESS) to enable peak shaving and storage of excess renewables mid-day. Seasonal storage has also been investigated in the form of “pre-screened” DOE pumped storage development sites in the greater San Francisco Bay Area, enabling up to 240 MW of longer-term energy storage. Although these approaches have not reached the policy development community, they do offer hope that the next generation of practitioners is focused on tactical approaches to address the issues.

But rooftop and other urban solar should grow sustainably. The alternative is unnecessarily excessive growth in large-scale solar with increased harm esp to public wild lands including the deserts. Plus, both the federal state government have declared that 30% of lands be set aside by 2030 (30 x 30) to preserve species and other environmental benefits, including maintaining carbon sinks. So any rules that don’t grow rooftop and other urban solar sustainably are more harmful to the environment.

The likely decision by the CPUC may be leading right to the very outcome that it is trying to avoid–mass customer departure. Here I compare the cost of an independent microgrid against PG&E’s projected rates (SDG&E has a similar problem): https://mcubedecon.com/2022/03/17/are-pges-customers-about-to-walk/ (A neighbor recently received a quote for a similar system that confirms NREL’s estimate.) Many of us foresee an acceleration of rooftop solar, but for the wrong reasons.

Existing distributed solar customers (about a third commercial whom the CPUC found to still be cost effective in the proposed decision) have reduced the CAISO peak load by 12% to 18%. The savings amount to $2 billion to $4 billion annually, offsetting claims of cost shifting: https://mcubedecon.com/2022/02/24/has-rooftop-solar-cost-california-ratepayers-more-than-the-alternatives/

Asserting that Tesla and Sunrun somehow have the same legislative clout at PG&E, SCE, Sempra and their affiliated labor unions ignores the long history of the latter group, most recently revealed in PG&E’s bankruptcy bailout and creation of the wildfire liability fund.

Not sure how the marginal cost of transmission can only be less than a penny a kilowatt hour when PG&E’s retail transmission rate component went from 1.469 cents per kWh in 2013 to 4.787 cents in 2022. By definition, the marginal cost must be higher than 4.8 cents (and likely much higher) to increase that much.

(I’ve already commented on the shortcomings of the cited studies linked in this blog on those posts.)

I think the issue can be simplified by acknowledging that retail sales cannot be sustained when the retail provider is paying retail for what they sell. They can’t fully cover their costs nor turn a profit that way. I am saying this as an “early adopter” who has PV on my roof.

Gerry, if the cost/value of the product being provided is higher than the retail price, then the transaction is sustainable. Through at least 2015 the value of rooftop solar was greater than the retail price based on the resources being deferred. Rates then accelerated due to inclusion of overpriced power contracts. At issue is what is the true value of those exports.

Due to the fact that the vast majority of the increase in rates is attributable to stranded assets, an important question is why is energy efficiency being penalized in the same way? Investing to reduce energy use from the grid in any manner reduces the load over which those costs are spread and therefore increases everyone else’s rates. This is a fundamental policy question–are we going back 40 years to punish those who don’t use grid power?

The new proposed decision comes closer to preserving a more level playing field for a new entrant (the solar industry) to compete with an established industry (the utility). That is something that an economist should treasure, not scorn.

Even the new proposed decision uses a flawed “avoided cost calculator” to value the power that a solar PV system produces. Generating power close to where it is used provides transmission, distribution, and line loss benefits that the avoided cost calculator fails to adequately recognize. It does this by valuing the “backfeed” to the grid at only a short-term value, when in fact every new PV system represents a permanent addition to grid capacity. A long-run marginal cost approach would include recognition of avoidance of the costs of building new transmission lines (otherwise needed to bring in solar power from Barstow) and similar avoided distribution costs.

This post continues the tradition of suggesting that a person who grows their own vegetable garden should somehow compensate the supermarket where they formerly bought produce for the lost revenues. By contrast, the proposed decision is more consistent with how real markets work. If you don’t buy produce at the supermarket, you avoid the retail price. But if you bring in your surplus tomatoes and squash, they will pay you only the wholesale value.

The effect of the proposed decision will be to encourage most new solar owners to install battery storage. That is probably a good thing in the greater scheme of things. That would have been inappropriate when NEM1 was approved under Governor Schwartznegger, or NEM2 was approved under Governor Davis. The technology was not ready. Today it is.

I think the backfeed rate included in the Proposed Decision is a little too low, not recognizing long-run avoided costs. But the principles underlying the revised Proposed Decision, allowing solar customers to connect to the grid for no more than the cost of connecting to the grid, and to avoid the time-varying retail price, are good principles. These come much closer to a rational relationship between the incumbent utilities and new entrants. That is a shift that every economist should appreciate.

There comes a time to move on from buggy to automobile, and from automobile to e-bike. Regulating rates to protect the buggy-whip manufacturers is not in our long-run public interest.

“This post continues the tradition of suggesting that a person who grows their own vegetable garden should somehow compensate the supermarket where they formerly bought produce for the lost revenues.”

Uh, except with NEM these are not “former” customers. They are still getting power from the utilities everyday, and probably every day even if they have a Powerwall (or two). Moreover, to take your analogy where it needs to go to compare with NEM, the people who you describe as “former” customers would be going to the supermarket with their home-grown produce and demanding that the grocer pay them more for that produce than what the grocer would pay buying the same thing at wholesale from another purveyor; and then the grocer would pass that additional cost to the supermarket’s customers.

But I’m sure that would somehow be in the best interest of going from something analogous to the automobile to the e-bike.

Kurt – thanks for correcting that analogy, you’re spot on.

Jim – the avoided cost calculator includes transmission and distribution investment deferral benefits, it assigns those benefits during hours of grid constraint. The ACC also credits clean distributed resources for deferring investments in supply side clean energy that would otherwise be needed to achieve California’s climate goals.

Some consider the T&D benefits in the ACC to be generous as they assume that in the long-run, DER will in aggregate defer investments at a rate commensurate with the correlation between T&D investments and increased electric demand.

The analysis I’ve seen some advocates make on the vary high transmission deferral value of rooftop solar is best described as a study in correlation, not causation.

Mohit

When correlation is very high and there’s no reasonable alternative explanation, then that implies causation. Only engineers want directly physical causation, but that’s not usually possible in complex systems like the electricity grid. Instead we have to rely on economic methods to derive those results.

Richard,

To conclude that the correlation is indeed causation, you need to at minimum explore other reasons why specific planned transmission projects were canceled. If you eliminate other plausible reasons, then you could consider putting forth the argument that correlation in this case may imply causation. To my knowledge this analysis hasn’t been conducted.

The ISO themselves refuted one such claim – that correlation of canceled transmission projects is due to increasing rooftop solar adoption – explaining the different reasons why certain transmission projects were canceled. https://www.caiso.com/Documents/Aug23-2019-ReplyComments-Calculation-AvoidedTransmissionCosts-DevelopDistributionResourcePlans-R14-08-013.pdf

M

Mohit

So we have several possible explanations for transmission investment–1) energy demand increase, 2) peak demand increase, 3) reliability reinforcements and 4) increased generation investment. In California, energy and peak demand have been basically flat (even decreasing much of the time) since 2006. The 2022 record peak only surpassed the 2006 record by 2,000 MW under unusual circumstances, and annual energy sales are less than then were a decade ago. Peak loads are 6,500 to 11,500 MW less than forecasted in 2006, and those forecasts included all of the energy efficiency/building standards that have been put in place over that period. The only additional unforeseen resource is 12,000 MW of distributed solar. So we can set aside all demand side measures other than distributed solar as displacing transmission. (I have presented in multiple rate cases how the utilities have continually overforecasted loads in their GRCs since 2006. They finally corrected their load forecasting problems in the last round of GRCs.)

We’re left with the supply side forces. 20,000 MW plus of grid scale renewables have been added since 2006. Transmission investment is largely created by increased generation, not increased demand based on the analysis. Increased distribution investment is caused by increased demand mostly. Solar rooftops displace generation, and since most new generation added in California in the last decade has been solar (with some wind), the generation shape matches that of utility scale solar. As for reliability, solar rooftops have shifted the peak 2-3 hours later in the day away from the peak electric use for space cooling (this differs from the peak metered use). That shift explains much of the reduced peak growth.

Engineers are not well equipped to identify “why” they made a large complex decision. That’s where economists come into play with a more holistic analysis that identifies the various factors impacting a decision. In fact, the method identified by CAISO is probably leading to the overbuilding for the transmission system and the reason why transmission rate components have skyrocketed over the last decade. (The CAISO filing doesn’t actually give any empirical proof about what has deferred investment–the document just hands off responsibility to the IOUs.) The problem with the CAISO method is that it attempts to identify which projects that were already identified were cancelled. We are actually looking for the transmission projects that weren’t even considered because (therefore not cancelled) reduced loads created by DERs removed the need for those projects. That can only be determined through economic, not engineering, analysis. It is the counterfactual case that is the starting point of the analysis, not current conditions, when doing a retrospective assessment.

You should come with an alternative that fits the facts that explains the high marginal costs of transmission–something is driving these costs so high that even the embedded costs are escalating rapidly. Reducing transmission load through DERs seems to be the best and perhaps only solution.

Scott

We have a grocery delivery network–it’s called “roads” and importantly its completely separate from grocery stores, functionally and financially. The electric utility analogy to the grocery store is generation and transmission (the wholesale food distribution network), and we know that for SCE the excess past costs being collected from customers is about a half of the total excess; for PG&E and SDG&E it’s approaching three quarters. A grocery store cannot pass through those excess costs. On the other hand, the excess costs in the distribution system are less than a quarter, and this is analogous to the roads maintained by the local government, a separate entity. As Jim points out, the justifiable monthly charge for that is between $5 and $25 per month for urban customers. (For rural customers it’s probably so high that most should be in separate microgrids.)

Jim

To follow up on your points, PG&E currently compensated master metered mobilehome park owners based on the cost to serve multi family customers. That’s about 40% of the average residential cost (and single family is much higher). We recommended that if PG&E is going to use this method for the service rate discount, that it also should be charging those customers the lower rate–PG&E refused, and TURN supported PG&E.

Ahmad’s point about customers using energy efficiency is to point out the disparate treatment of two different classes of customers who largely provide the same service to the grid. Rooftop solar customers also displace energy deliveries, yet we claim they have cost responsibilities that customers who installed energy efficiency apparently do not. Given that at least 75% of excess costs above LRMC are stranded above market costs created by poor management decisions, it’s not clear what one set of customers get to escape some form of obligation while another does not. Greendave makes essentially this same observation.

I am a supermarket customer.

I do grow some of my own produce.

When I don’t have enough tomatoes, I can go to the store and buy more at exactly the same price other people (who do not grow any) pay. No price discrimination.

I already agreed that when I take my surplus produce to sell, I should get the wholesale price, not the retail price. But, since my tomatoes are local, vine-ripened, organic tomatoes, the wholesale price I might receive could easily be equal to the retail price of ordinary “grid” tomatoes that the store sells.

That is, the solar kilowatt-hours supplied to the grid must be valued as renewable energy injected into the system at the distribution voltage level, avoiding generation, transmission, and distribution costs and losses.

As Mohit pointed out, the wholesale value of solar “as-available” is dramatically lower than it used to be, and all parties in the CPUC NEM3 docket agree that backfeed should be valued at a price lower than retail.

But, in low-cost jurisdictions (my retail price from Puget Sound Energy is under twelve cents, no time differentiation), the value of a clean kWh delivered into the grid near where it will be consumed could easily be worth the retail price or more, obviously depending on time and place.

Jim, you’re analogy is inapt because it glosses over a key distinction between goods delivered by public utilities and other non-utility goods. The supermarket didn’t have to build a capital-intensive distribution network of pneumatic tubes to deliver food to every household. If, for some weird reason, people just couldn’t just go to a market to buy their food and had to buy it from a pneumatic tube-based delivery system, then the analogy would hold water, and we’d have to wrestle with the same fixed cost vs variable cost dilemma that plagues all cost allocation decision for public utilities. Should all costs be recovered volumetrically? Does that mean a family of six should pay 6x the embedded cost of the pneumatic tubes than a single-person household even though there’s little marginal cost to using the tubes? Or should all household pay a connection fee that covers all, or some portion, of the fixed cost on an equal per-household basis?

Grocery companies DO build a large distribution network, to get food from where it is produced to a supermarket just a few blocks from my home.

I directly bear the cost to “connect to the grid” by walking, cycling, or driving to the store. THE REST OF THE COST of the distribution system that brings me Brie from France, Steinlager from New Zealand, and Cheerios from Battle Creek, Michigan is built into the price for each item.

And, they provide free delivery on orders of $35 and above. And, when an actual Kroger employee delivers, they refuse tips. So I don’t actually have to pay anything for the “last mile” of delivery.

You may argue that the “obligation to serve” implies a different cost recovery. I respond simply by saying that my local supermarket provides more reliable service than my electric utility, so apparently the competitively-driven DESIRE to service is more powerful than any statutory OBLIGATION to serve.

In our book, Smart Rate Design for a Smart Future, we suggested a similar approach to rate design. Rates should have three components:

a) A fixed customer charge, to recover billing and collection expenses;

b) a site infrastructure charge, to recover the customer-specific distribution costs, meaning (at most) the cost of the final line transformer and service drop; about $5/month for an apartment or small house, up to $10/month for a customer in a large rural home with a dedicated transformer.

c) A TOU energy charge to recover all generation, transmission, and primary distribution costs. All of those facilities are sized to meet the needs of MANY customers, not the specific loads of ANY customer, so they should be recovered on a TOU basis.

The Hawaii PUC just ordered a rate design of this type.

The California decision combines the first two into a $15 customer charge — approximately right, but it overcharges people in apartments and small homes, and undercharges rural customers with dedicated transformers. BUT, since most of the solar customers are suburban customers in single-family homes, it’s “about right.”

The only remaining piece is the backfeed rate, and we have genuine disagreement on what marginal transmission and distribution costs are. I believe in measuring marginal cost on a “total service” basis — what would it cost to build an optimal system today, with today’s technology, to serve today’s loads.

The Avoided Cost Calculator takes a MUCH narrower view of marginal costs. And that is where, I think, Scott Murtishaw and I disagree: the time frame over which marginal costs are measured, and the treatment of sunk costs (and existing capacity) in a marginal cost study. I think that is a principled disagreement, not an “error” on my part (or Scott’s). We simply approach the problem differently, and we reach different conclusions.

Using a total service approach avoids discriminating against new entrants. They can compete against the full cost of service that a utility incurs, not a partial cost of service. That is one goal of the competitive market framework that we teach in economics.

Jim, you’re glossing over a key distinction between goods delivered by public utilities and other non-utility goods. What if, for some weird reason, people could only buy food from a system of pneumatic tubes connected to every household? In that case, should fixed costs be recovered volumetrically? Should a family of six pay 6x the embedded cost of the system than a single-person household even though there’s little marginal cost to using pneumatic distribution system? Or should all, or some portion, of the fixed cost be recovered via a fixed, per household connection fee?