Everyone Should Pay a “Solar Tax”

Monthly connection fees are good for the climate.

Regular readers of this blog are well aware that the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) published a proposed decision on reforming net energy metering (NEM) for residential rooftop solar last December. One of the most contentious elements of the proposed decision is a requirement that households that install solar power in the future pay a monthly fixed connection fee to help cover the various fixed costs associated with distributing electricity in California. This has been derided as a “Solar tax” since, under the proposal, only solar homes would pay the connection fee .

Over the last few months there have been several head-scratching and, I would argue, misguided arguments put forward in favor of preserving the NEM status quo. The most curious one is the widely circulated argument that NEM reform would constitute a step backwards in California’s climate leadership. In fact, the opposite is true. For many years, NEM has been a growing impediment to the centerpiece of California’s current climate plan – electrification of households and transportation.

How could NEM be impeding climate progress? It’s really not that complicated.

- Under the current NEM, homes with rooftop solar do not contribute much to the cost of electricity infrastructure, wildfire mitigation and compensation, investments in new clean technologies, and many other programs utilities are required to pay for.

- Those costs are still recovered through the price of electricity, so the more homes that go solar, the higher the cost of electricity for everyone else. This is the real solar tax – one that is paid by non-solar homes.

- Higher electricity prices make the shift to electric vehicles, space heating, and water heating less and less appealing to the majority of Californian’s whom the state’s own climate scoping plan is counting on to electrify their lifestyles.

Critics of the CPUCs proposed decision point to the fact that in the parts of California where NEM has already been changed – places, by the way, with publicly-owned utility systems and not “profit-seeking” investor-owned utilities – solar installations have declined sharply. The implication is that this is in turn stalling progress toward renewable energy goals. That’s just not true. This perspective ignores the fact that residential rooftop solar isn’t the only way to generate clean electricity. It’s not even the only way to generate solar electricity. It is only the most expensive way to generate clean electricity.

“Dirty” Energy Displaced by Rooftop Solar

Given that the state has already committed itself to 100% clean electricity, rooftop solar doesn’t make the grid any cleaner, it simply crowds out other, less expensive, types of clean electricity. So NEM reform won’t hurt the solar industry, or make our electric system any less clean, it will just hurt the residential rooftop solar industry.

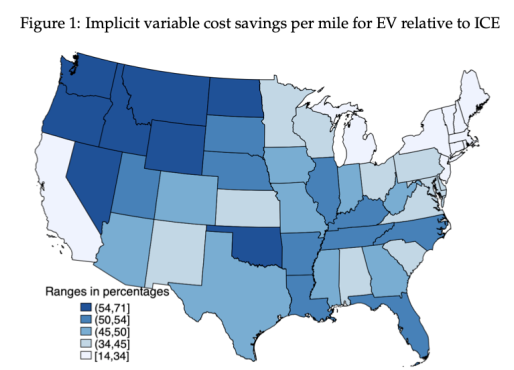

What NEM reform would do is help slow the inexorable increase in electricity prices for non-solar homes. This in turn would help stave off the very real possibility that fueling an electric car in California becomes more expensive than fueling a conventional one. According to research by Dave Rapson and Erich Muehlegger at UC Davis, fuel savings from EVs are already lower in California than almost anywhere else.

Savings per mile from driving EVs (Rapson and Muehleggar, 2022)

My own recent research with Severin Borenstein indicates that electric appliances and vehicles should be much cheaper to use than they actually are at current electricity prices. Heating houses and water with electricity is penalized relative to gas in California, even though it should cost about the same. So, if we really cared about climate goals, we wouldn’t be focused on providing electrification incentives just for solar homes at the cost of everybody else.

The solution, which makes too much sense to ever be widely adopted in California, is to make NEM irrelevant. We have spent too long arguing about the rates paid by solar homes and not enough time talking about the rates paid by everyone else. The proposed monthly fixed charge (e.g. solar tax) is simply a means of recovering the fixed costs of distributing electricity in California. But we shouldn’t stop at only the solar homes. The road to electrification is to shift everyone to a rate structure that encourages electrification, one that accurately reflects the high costs of connecting to the grid and the low costs of actually consuming electricity.

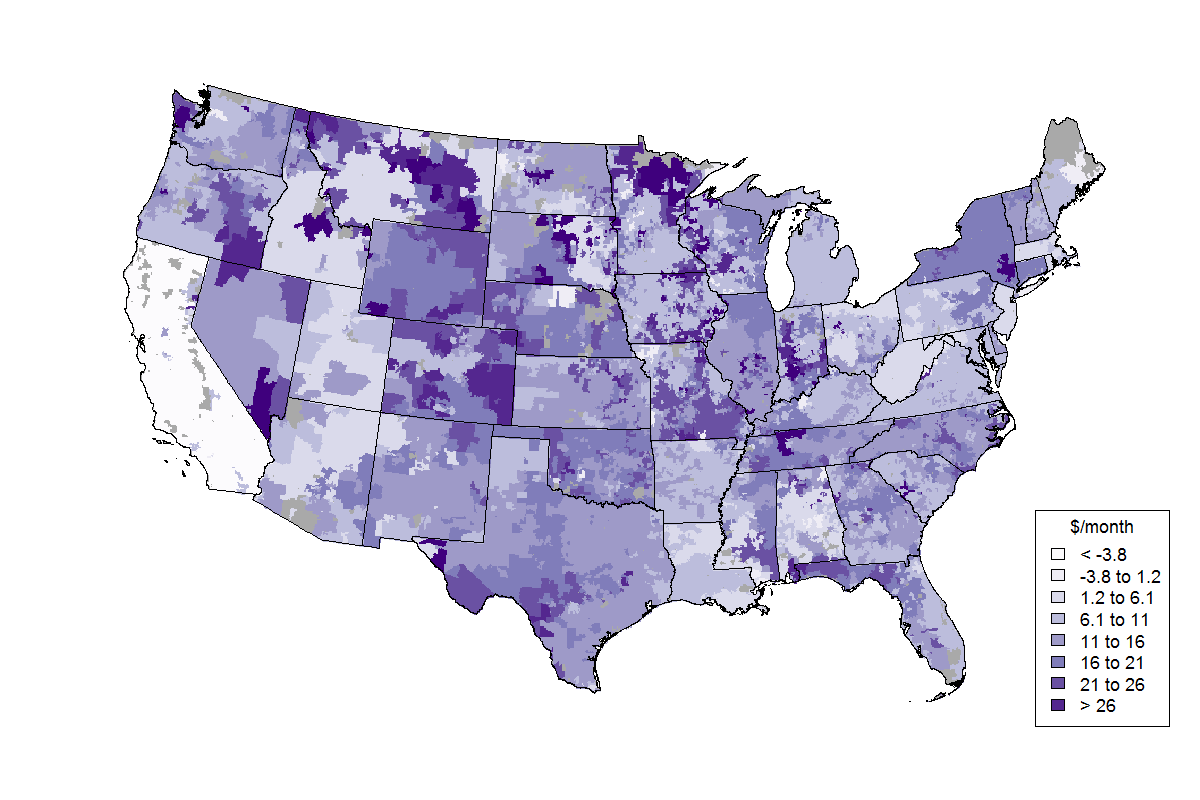

This means moving everyone to a monthly connection charge and lowering the marginal price of electricity by an amount that offsets the revenues raised by the connection fees. It’s not a revolutionary idea. Lots of electric utilities already do it. Our gas utilities in California already do it. In fact, California’s CPUC regulated electric utilities are about the only utilities in the country to not charge a monthly connection fee.

Monthly Fixed Charges for Residential Electricity Service (Darker is Larger)

Monthly Fixed Charges for Residential Electricity Service (Darker is Larger)

So why hasn’t California moved toward this two-part pricing structure? One reason has been equity concerns. These can be dealt with by creating low-income connection fees, or other more creative solutions. The other reason is that it would hurt the rooftop solar industry. If all homes faced volumetric (per kWh) prices that reflected the true cost of electricity, few would see an appeal to paying twice as much for rooftop solar power. However, in California, we seem to be more concerned with making 10% of our households really, Really, REALLY clean than with getting serious about actually reducing total statewide greenhouse gas emissions.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Bushnell, James. “Everyone Should Pay a “Solar Tax”” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, February 14, 2022, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/02/07/monster-trucks/

Categories

First, I agree that charging everyone a connection charge is a reasonable solution. The question is what that connection fee should be? Much less of the distribution costs are “fixed”–we can see an example of the ability to avoid large undergrounding costs by installing microgrids as an example: https://mcubedecon.com/2021/10/26/comparing-cost-effectiveness-of-undergrounding-vs-microgrids-to-mitigate-wildfire-risk/ SCE has repeatedly asked for a largely fixed “grid charge” for the last dozen years and the intervenors have shown that SCE’s estimate is much too high. A service connection costs about $10-$15/month. There’s a strong economic argument that if the utility is collecting a fixed charge for upstream capacity, then a customer should be able to trade that capacity with other customers. In the face of transaction costs, that market would devolve down to the per kWh price managed by the utility acting as a dealer–just what we have today. How to recover stranded costs really requires a conversation about how much shareholders should shoulder. Distributional public purpose costs should be collected from taxes, not rates. Energy efficiency is a resource that should be charged in the generation component, not distribution. The problem is that decoupling has become a backdoor way to recover stranded costs without any conversation about whether that’s appropriate–rates go up as demand decreases with little reduction in revenue requirements. So what the connection charge should be becomes quite complex.

Second, there are at least two premises here that run counter to the empirical evidence.

First, in 2005 the CEC forecasted the 2020 CAISO peak load would 58,662 MW. The highest peak after 2006 has been 50,116 MW (in 2017–3,000 MW higher than in August 2020). That’s a savings of 8,546 MW. The correlation of added solar rooftop capacity with that peak reduction is 0.938. Even in 2020, the incremental rooftop addition was 72% of the peak reduction trend. We can calculate the avoided peak capacity investment from 2006 to today using the CEC’s 2011 Cost of Generation model inputs. Combustion turbines cost $1,366/kW (based on a survey of the 20 installed plants–I managed the survey) and the annual fixed charge rate was 15.3% for an annual cost of $209/kW-year. The total annual savings is $1.8 billion. The total revenue requirements for the three IOUs plus implied generation costs for DA and CCA LSEs is $37 billion. So the annual savings that have accrued to ALL customers is 4.9%. Given that NEM customers are about 4% of the customer base, if those customers paid nothing, everyone else’s bill would only go up by 4% or less than what rooftop solar has saved so far.

Second, rooftop solar isn’t the most expensive power source. My rooftop system installed in 2017 costs 12.6 cents/kWh (financed separately from our mortgage). In comparison, PG&E’s RPS portfolio cost over 12 cents/kWh in 2019 according to the CPUC’s 2020 Padilla Report, plus there’s an increments transmission cost approaching 4 cents/kWh (https://mcubedecon.com/2021/07/13/transmission-the-hidden-cost-of-generation/), so we’re looking at a total delivered cost of 16 cents/kwh for existing renewables. (Note that the system costs to integrate solar are largely the same whether they are utility scale or distributed).

But perhaps most importantly, the premise that there’s a “least cost” choice implies that there’s some centralized social welfare function. This is a mythological construct created for the convenience of economists (of which I’m one) to point to an “efficient” solution. The real actors here are individual customers who are making individual decisions in are current economic resource allocation system, and not a central entity dictating choices to each of us. Different customers have different preferences in what they value and what they fear. Rooftop installations have been driven to a large extent by a dread of utility mismanagement that makes expectations about future rates much more uncertain. The single most important aspect of a market economy is the discipline imposed by appropriately assigning risk burden to the decision make. Market distortions are universally caused by separating consequences from decisions. And right now the only ability customers have to exercise control over their electricity bills is to somehow exit the system in some manner. If we take away that means of discipline we will never be able to control electricity rates in a way that will lead to effective electrification.

The real threat to electrification are the rapidly escalating costs in the distribution system, not some anomaly in rate design. PG&E’s 2023 GRC is asking for a 66% increase in distribution rates by 2026 and average rates will approach 40 cents/kWh. We need to be asking why are these increases happening and what can we do to make electricity affordable for everyone.

You are very correct on all your assumptions. Considering that PG&E is going to be allowed to re-coup all its losses from the fires from ratepayers including the fines and judgments, it may be better to get off the grid with your own solar panel system with batteries and a backup generator than pay to bail out a failing utility. A 10,000 watt off-grid system, with 2 – 14,000 what hour batteries and a backup 10,000-watt generator amortized over 25 years with a onetime lithium battery replacement is 24 Cents per kilo watt hour generated and used using today’s costs for that system. That system would conservatively produce 250,000 Kilo Watt hours over its lifetime and cost about $60,000.00 to build minus any government rebates. The PG&E proposed rates of 40 cents per kilo watt hour delivered would be $100,000.00 over 25 years for the same 250,000 kilo watt hours or $40,000.00 more than a fully, self-contained solar with battery and generator backup system.

“First, in 2005 the CEC forecasted the 2020 CAISO peak load would 58,662 MW. The highest peak after 2006 has been 50,116 MW (in 2017–3,000 MW higher than in August 2020). That’s a savings of 8,546 MW. The correlation of added solar rooftop capacity with that peak reduction is 0.938. Even in 2020, the incremental rooftop addition was 72% of the peak reduction trend.”

Richard, are you imputing the full 8,546 MW of peak load forecasting error to behind-the meter solar production? What about other factors, e.g., more energy efficiency additions, weather, population growth error, other forecasting errors? But even if the peak reduction were entirely due to BTM solar, residential rooftop solar is only about one-third of that. The other two-thirds consists of community solar and small C &I solar. That reduces your estimate by two-thirds.

“We can calculate the avoided peak capacity investment from 2006 to today using the CEC’s 2011 Cost of Generation model inputs. Combustion turbines cost $1,366/kW (based on a survey of the 20 installed plants–I managed the survey) and the annual fixed charge rate was 15.3% for an annual cost of $209/kW-year. The total annual savings is $1.8 billion.”

$1366/kW is reasonable for aeroderivative CTs but way too high for typical industrial CTs. EIA estimates the overnight cost of these large CTs to be about $850/kW installed in California. Also, the 15.3 percent annual capital carrying charge seems too high if levelizing in real dollars. I calculated this charge for a new CT installed in California and got a value of 12.8 percent.

If you only considered aeroderivative CTs because of their fast ramping capability then you also have to recognize that their higher cost is caused by the need to respond to the rapid change in solar output in the morning and evening, That means the incremental increase in cost should be imputed to all solar facilities causing the need for fast ramping.

In light of these two changes I don’t think it is worth further work to show that your benefit calculation defending residential rooftop solar isn’t credible.

“Second, rooftop solar isn’t the most expensive power source. My rooftop system installed in 2017 costs 12.6 cents/kWh (financed separately from our mortgage). In comparison, PG&E’s RPS portfolio cost over 12 cents/kWh in 2019 according to the CPUC’s 2020 Padilla Report, plus there’s an increments transmission cost approaching 4 cents/kWh (https://mcubedecon.com/2021/07/13/transmission-the-hidden-cost-of-generation/), so we’re looking at a total delivered cost of 16 cents/kwh for existing renewables. (Note that the system costs to integrate solar are largely the same whether they are utility scale or distributed).”

I have done levelized cost calculations for residential rooftop solar installed in California and got numbers close to your estimate. Note that financing your system with tax-deductible debt (which you apparently did) reduces the llevelized cost by about one cent per kWh. That’s a subsidy you received through the federal income tax code in addition to the 30 percent Federal REEP.

Comparing the levelized cost of your solar to the value in the Padilla report doesn’t make sense. The Padilla report appears to be presenting the average cost per kWh of solar energy using the cumulative cost of all past solar procurements, which include a lot of high-priced PPAs from previous years.

The appropriate comparison should be with the current cost of utility-scale PPAs, which the Padilla report states are in the range of 3 cents per kWh. A recent LBNL report also shows similar PPA prices.

https://emp.lbl.gov/utility-scale-solar/

The Padilla Report and the LBNL study reveal that utility-scale solar is currently about one-fourth the cost of residential rooftop solar.

“But perhaps most importantly, the premise that there’s a “least cost” choice implies that there’s some centralized social welfare function. This is a mythological construct created for the convenience of economists (of which I’m one) to point to an “efficient” solution. The real actors here are individual customers who are making individual decisions in are current economic resource allocation system, and not a central entity dictating choices to each of us. Different customers have different preferences in what they value and what they fear. Rooftop installations have been driven to a large extent by a dread of utility mismanagement that makes expectations about future rates much more uncertain. The single most important aspect of a market economy is the discipline imposed by appropriately assigning risk burden to the decision make. Market distortions are universally caused by separating consequences from decisions. And right now the only ability customers have to exercise control over their electricity bills is to somehow exit the system in some manner. If we take away that means of discipline we will never be able to control electricity rates in a way that will lead to effective electrification.”

I agree with much of what you say here. But let’s point the finger at the real culprits behind the IOUs’ dysfunctional retail electricity rates: the legislators and the CPUC. The IOUs didn’t dream up these ridiculous rate designs all by themselves. They did so to satisfy what the CPUC wanted. I can’t blame homeowners from wanting to bypass those rates by installing solar. That’s an unintended consequence of bad rate making. Maybe the current imbroglio over NEM will be a wakeup call. I hope it is.

“The real threat to electrification are the rapidly escalating costs in the distribution system, not some anomaly in rate design. PG&E’s 2023 GRC is asking for a 66% increase in distribution rates by 2026 and average rates will approach 40 cents/kWh. We need to be asking why are these increases happening and what can we do to make electricity affordable for everyone.”

You raise a good point. If these costs are being driven by the need to bury cables underground in wildfire areas why not bill those costs to the customers living there? It may be cheaper for them to just buy home generators and disconnect from the grid. Or maybe move to safer areas. Why should those distribution costs be socialized?

One more thing, In 2005, we did not have LED lighting or LED flat screen TVs and if they reduce the average homes lighting costs by 85% and 10 % of a home electrical usage is for lighting. LED have saved 8.5% of the energy that has been forecasted in 2005 usage by 2020. All the new refrigerators have compressor motors that draw 100 Watts while running and older pre-2005 refrigerators had compressors that drew 230 watts to run. The new 55-inch UHD televisions draw 95 watts while the old boxy 25-inch sets drew 350 watts. Energy Star appliances and lighting have contributed to a 20 to 25% reduction in use in homes and businesses so saying the Solar is costing the utilities money is a laugh. Energy efficient lighting and appliance adoption by homeowners and businesses hase done more to reduce usage and thus affect the utilities bottom line of overall sales far more than rooftop solar.

Most, if not all, of those energy savings were already baked into the CEC’s forecast in 2005 because the CEC includes the planned and prospective standards. In fact, the utilities have long argued that the CEC is overly optimistic in its energy efficiency assessments, and the IOUs used their own forecasts for procurement and distribution planning, which is why they got into their overprocurement predicament. I detailed on testimony in PG&E and SCE cases about the utilities’ biased-high forecasts. The only truly unanticipated new innovation from 2005 to 2020 has been the installation of distributed solar.

“In fact, the utilities have long argued that the CEC is overly optimistic in its energy efficiency assessments, and the IOUs used their own forecasts for procurement and distribution planning, which is why they got into their overprocurement predicament. I detailed on testimony in PG&E and SCE cases about the utilities’ biased-high forecasts.”

Richard,

Load forecasts always contain error. However, it is preferable to over-forecast than to under-forecast load because the cost of being caught short is far higher than the cost of being too long. Rolling blackouts impose costs that are an order of magnitude higher than the costs of carrying excess capacity.

The primary responsibility of a utility is to keep the lights on (except for Texas where the IOUs have no obligation to serve and we all saw how that worked out in 2021).

But you raise an important point. Did you estimate the cost was of the excessive procurements? I’m wondering how much that has driven up the IOUs’ retail rates.

Good response Robert (re: Richard’s attribution of peak reduction to rooftop solar). Another thing to consider is that there was an economic recession after 2005 that impacted electricity demand as well.

Mohit, read my follow-up. Robert misinterpreted the statistics. The residential load reduction was proportional between DER solar and customer load shares.

Max Sherman is correct regarding the public good nature of clean air and reduced greenhouse gases. However, he is incorrect in stating that taxpayers should bear the cost of reducing the emissions of fossil fueled electric generators. What he overlooks is the well established principle of cost causality, i.e., the party causing the cost should pay for that cost. So who are the parties causing the costs of generator emissions? Obviously electricity consumers are. His claim that “…carbon reductions from renewable energy has no particular benefit to the person using electricity…,” is essentially true – but irrelevant.

All of California’s electricity customers already pay a solar tax because they directly pay for the Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) their electric utilities must buy (or create). This includes both the publicly-owned utility systems as well as the three investor-owner utilities. The added cost of Net Energy Metering (NEM) is pancaked on top of the REC costs, especially for customers without rooftop solar. These REC costs are another reason why California’s electricity rates are so high. Contrary to what the advocates claim, renewable energy IS NOT cheaper than electricity produced with fossil fuels; if it were RECs would have zero value.

As Jim Bushnell correctly pointed out, residential rooftop solar is the most expensive way to produce renewable energy (except for offshore wind, which thankfully Californians are not saddled with – yet). Every dollar spent on these Ma and Pa solar arrays is a dollar that could have been more productively spent on community solar or utility-scale solar and most likely would have been but for the exorbiant subsidies produced by NEM when combined with the outrageously high retail energy prices imposed by the CPUC.

That said, Max Sherman does make a valid point in claiming that the cost of various social programs, such as subsidizing low income households, should be paid for with general tax revenues. In these cases there is no causal connection with electricity consumption so saddling electricity customers with these costs makes no sense. He also correctly points out that the legislators would much rather hide these costs in electric rates, rather than take responsibility for imposing them.

Lastly, I agree that the CPUC’s attempt to retroactively withdraw NEM from existing solar customers who invested based on the projected savings from NEM, is indefensible, despite the shortcomings of NEM. After all, a deal is a deal – even a bad one.

i totally agree with your arguments. I installed two Solar panel systems on my home. The first one was an 8,000-watt system with batteries that fed my home without mixing with grid tied circuits. The second was a Tesla Solar Glass Roof with 7,850 watts of active solar roof tiles. without batteries because Tesla did not have any to install at the time the roofing job was done. The Off Grid system pro rates, with periodic battery replacements at 18 cents per kilo watt hour after the one-time federal tax credit on the first set of batteries and no NEM contract or fees at all. The Tesla Solar Glass Roof for the 7850 watts of solar installed and pro-rated for 25 years is 9 cents per kilo watt hour under NEM-2.0. However, if the $8.00 monthly fee was added for the 25 years and you could not get the full credit for power placed on the grid and reused before true up, the cost per Kilo Watt hours would jump to19 cents per kilo watt hour and one would also have to buy back 30% of the power at retail since you would not get credits for it during the summer months under the proposed NEM-3.0. At this point, the off-grid battery-based system would cost less than the om-grid non battery system with fees and lower credits. Both systems would be less than the March 1, 2021, averaged electrical rate of 28 cents per kilo watt hour from PG&E but the system without batteries could no run without the grid being powered on and the battery-based system could. If you installed an on-grid system with two power wall batteries, your total cost per kilo watt hour, with replacement and original battery installations included over 25 years would be a whopping 32 cents per kilo watt hour under NEM-3.0 after the federal tax credits on the original system with batteries. No one would do it if doing nothing costs 28 cents per kilo watt hour. you might as well invest the $62.000.00 the system would cost you over 25 years in the stock market.

Note that PG&E is requesting that rates go to over 36 cents per kWh by 2026 in its 2023 General Rate Case, and that’s before it adds another $15 to $40 billion in ratebase to underground 10,000 miles of power lines in fire risk zones.

The state made the decision to move California to 100% renewable, not the CPUC and not the residential and business customers. Similarly, climate change is being used as the justification for PG&E’s very expensive burying of its power lines that serve all. NEM cost calibration is just a placeholder for the bigger issue:

Place these “costs” where they belong, with the taxpayers of the state. The state should be the ox pulling this cart, and not the CPUC and not the energy consumers, especially with the robust surplus in taxes (but not in utility revenues). By providing the revenue to fund these societal goals from the general taxpayers whose representatives legislated it, we collect the money from those that voted for it and make the bulk of the money to pay for it. This avoids the taxes on the disadvantaged who cannot afford it (and the CPUC to come up with ways to solve a political problem) or the businesses that consume, and places the cost based on their taxable profits.

Instead of using the sleight of hand of running these costs thru the CPUC, own the decision, tax the decision, and get the rich to pay for the decision. The raised funds can then be administered by the CPUC and the only question they will have to address is if and when the utilities actually spent the money wisely and timely, a role the CPUC is ideally bred to accomplish.

Big surprise. Other states that did not follow California in turning electricity systems and electric utilities into energy policy playgrounds and market facilitators now are better able to afford what California wants to do next. All would still be well in California except for the folks who see on-site solar as a hedge against further electricity market gyrations and rate escalation. Really?

I have to admit I’d rather see the CPUC do a good job evaluating the option of fixed charges for all than figuring out how to instantly repurpose the state’s rooftop solar industry to deliver solar paired battery storage.

How about focusing the CPUC and automakers on allowing EV owners to get the electricity they put into electric vehicles back out when they (and/or “the grid”) need it?

Big surprise. Other states that did not follow California in turning electricity systems and electric utilities into energy policy playgrounds and market facilitators now are better able to afford what California wants to do next.

All would still be well in California except for the folks who see on-site solar as a hedge against further electricity market gyrations and rate escalation. Really?

I have to admit I’d rather see the CPUC do a good job evaluating the option of fixed charges for all than figuring out how to instantly repurpose the state’s rooftop solar industry to deliver solar paired battery storage.

How about focusing the CPUC and automakers on allowing EV owners to get the electricity they put into electric vehicles back out when they (and/or “the grid”) need it?

“I have to admit I’d rather see the CPUC do a good job evaluating the option of fixed charges for all than figuring out how to instantly repurpose the state’s rooftop solar industry to deliver solar paired battery storage.”

LOL! Well said.

“How about focusing the CPUC and automakers on allowing EV owners to get the electricity they put into electric vehicles back out when they (and/or “the grid”) need it?”

Also, lowering the volumetric energy charge would do wonders to encourage people to switch from natural gas heating to heat pumps and electric water heaters. Instead the politicians are banning the use of natural gas.

California just can’t resist putting bandaids on the bandaids instead of solving the underlying problem. It was not like that when I lived there 50 years ago (how time flies).

The CPUC has mandated a 73% renewable clean energy by 2032. If rooftop, school parking lots, commercial rooftop solar are not included in the mix, because high fees would kill of any incentive to install it, where would you get the 73% from? Before the rooftop energy existed, only windmills were given preferential monetary compensation during the jimmy Carter administration and that ended with Ronal Reagan and we were set back 20 years because everyone was gun shy of political changes in Washington wiping out any gains. That went for solar hot water heating as well when all the companies filed for bankruptcy protection when the tax credit ended. This left rooftop solar water heater warrantees eliminated for customers who still owned the systems with warrantees on their systems. Most hot water systems, when they broke down, were removed from the roofs and those people now are also gun shy from putting out huge amounts of money only to see no way to repair their solar panel system if it breaks down. NEM-2.0 already compensated utilities financially with their time of day and tiered tariffs in place. Electric rooftop energy is produced during the low period in tier 1 and the homeowners has to buy it back at high period at tier 2 in the winter. The early afternoon power, from solar rooftops, School solar systems and commercial solar rooftop systems not only powers other home air conditioning but industrial and commercial establishments as well. if everybody had to remove their rooftop solar because the companies that warrantee and service the solar panels were put out of business by NEM-3.0 as written, then California would be set back again 20 years, and no one would trust the California Government to provide incentives that could not be re-written at the stroke of a pen in Sacramento.

Who is arguing for the removal of existing residential rooftop solar panels? This is a red herring.

I do agree that existing solar customers should be grandfathered and allowed to continue to take service under NEM 2.0. That would support companies in the business of maintaining solar systems.

California does not need more residential solar to decarbonize. In fact, for all of the money spent subsidizing residential solar, it produces less than 10 percent of the State’s solar energy.

Total installed utility-scale solar is 14,060 MW (https://ww2.energy.ca.gov/almanac/renewables_data/solar/index_cms.php#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20solar%20PV%20and,14%2C060%20megawatts%2C%20are%20in%20California.)

Total distributed solar (of which most is rooftop) is 11,256 MW

https://www.californiadgstats.ca.gov/

Utility scale is 56% of installed capacity and distributed is 44%. Utility scale has a bit higher capacity factor because most are built in high insolation desert locations, but distributed solar is much more than 10% of total solar generation.

Richard,

You are co-mingling residential rooftop solar with distributed community and small C&I solar. Residential rooftop solar only represents about 1/3 of all distributed solar.

Utility-scale solar has significantly higher capacity factors because much of it employs single- and two-axis tracking while rooftop solar is fixed and typically not optimally oriented because of the architectural configuration of the roof.

Account for those two factors and you will find that residential solar produced a little less than 10 percent of total solar energy production in 2020.

I read, that NEM-3.0 was going to place A flat fee of $1,200 per month on public schools that installed solar panels on buildings and over parking lots. My local middle school, place solar panels over the teachers parking lot and they barely get back $600.00 per month in electrical savings. that would be a negative $600.00 per month if that fee was enacted. Would you keep the $600.00 a month losing proposition in place if you were on a school board financial committee? The flat fee was for behind the transformer, High school student parking lots and roof top solar arrays that usually have 200 to 500 kilowatts of solar installed. that get $75,000.00 to $200,000.00 of solar savings each year. Elementary and middle schools only put up 15 Kw to 50 kw since they are smaller with small parking lots only get $3,000.00 to $12,000 of solar savings a year on their systems. This is no Red Herring. Those parking structure covers cost a lot more than rooftop solar panels systems and they were also going to be hit by NEM-3.0.

“I read, that NEM-3.0 was going to place A flat fee of $1,200 per month on public schools that installed solar panels on buildings and over parking lots. My local middle school, place solar panels over the teachers parking lot and they barely get back $600.00 per month in electrical savings. that would be a negative $600.00 per month if that fee was enacted. Would you keep the $600.00 a month losing proposition in place if you were on a school board financial committee?”

I have previously stated that all customers with solar should be grandfathered under the rules that applied when they invested in solar.

However, if the $1,200 flat fee is imposed (which does seen excessive), the rational decision for the board to make is to retain the solar facility and eat the loss. Removing the solar would only increase the monthly loss. The school’s investment in solar is a sunk cost.

The relevant issue is how to change NEM so that solar installed in the future is cost-efficient and pay’s its fair share of the utility’s fixed costs.

First, commercial accounts such as those used by school districts would be treated differently than residential NEM customers and would not be charged the flat fee. In addition in the proposed decision. The focus of the PD is largely on residential NEM.

Second, parking lot shade structures are cheaper than rooftop solar, and when transmission costs are accounted for, are cost competitive with grid scale solar. The Lazard reports show the comparable costs.

I was so shocked by the title of this because I thought maybe the Energy Institute had finally realized the right path for this problem, but alas the content belied the title.

Indeed EVERYBODY should pay the solar tax–not just ratepayers. The benefits California accrues by encouraging renewable energy are a public good shared by all of us. Embedded carbon is in everythign we do and produce. The carbon reduction from renewables has no particular benefit to the person using the electricity, but is the same whether you are a big or minimal user. So indeed it should be paid by everyone.

That suggest it should be paid through general taxes, but the Energy Institute and others insist on believing that charging utility customers for truly public goods is the right way to go. This attitude started perhaps with low-income subsidies. It was politically much easier to charge ratepayers than to raise general taxes–even though there is no logic as to why ratepayers should pay for a socio-economic, public good. It is ironic that the principle complaint now is that paying for the solar public benefit from ratepayers is in conflict with that earlier socio-economic public benefit charged to ratepayers.

California has high rates in part because we have pushed true public goods programs onto ratepayers. To the extent that can’t be fixed, the public good cost of the programs should be spread evenly per ratepayer–since everyone benefits from improved environment. The fact that this is putatively unfair to low-income ratepayers is not the fault of the people who are willing to invest in solar; it is a failure of public policy.

It is heinous to go back on the deals with prior solar investors–whether those were good deals or bad. Going forward we need to look at different policy approaches than the current “hot potato” of which ratepayer gets stuck with the public goods cost. Income to pay for public goods must either come from direct “sin” taxes such as on carbon, or from the general fund that presumably raises money fairly.

The article reflects a long-critiqued “fallacy of composition” problem.

I’ll start with the map of monthly fixed charges. Most rural utilities have relatively high fixed charges. They serve the majority of the territory of the US, but only about 20% of the households. The vast majority are served by investor-owned utilities that provide service in cities and suburban areas, and very few of these have monthly fixed charges to recover any distribution system or upstream costs. Nearly every regulatory body in the Country has adopted rates based on the “basic customer” method, in which the monthly fixed charge recovers the cost of billing, collection, metering, customer service, and other costs that actually vary with the number of customers. For the ten largest utilities in the country (which serve about one-third of the population), only one has a fixed charge above $10/month, the same as the California minimum bill.

Next, in most of the country, despite low fixed charges, the volumetric price for electricity is in the range of $.09 – $.13/kWh, less than half what is charged in California by the IOUs. That is derived from their average costs, but happens to also match their relevant marginal costs quite well. The study that Dr. Bushnell and Dr. Borenstein published recently does a good job of measuring marginal environmental costs, but uses too-short a time horizon to capture marginal generation, transmission, and distribution costs adequately; when these are included, the relevant marginal costs are in the $.13/kWh range. That matches the retail volumetric price in most of the country, but again, California prices are higher.

The more useful research to pursue is to find out WHY retail electricity prices in California are double those in most of the country. Is it the commitment to clean energy and wildfire mitigation (in which case perhaps general taxes, not electricity prices, should carry some of the burden)? Is it excessive allowed shareholder returns and executive compensation? Is it the manner in which energy efficiency and low-income assistance programs are funded? Is it because the weather is better in other places, and the utility does not need to pay lots of of overtime to fix broken lines during storms (I think the opposite it true). Is it high labor rates or excessive economic regulation?

And maybe some of these same issues explain why natural gas also costs more in California. And gasoline also costs more in California. It’s always surprised me that groceries, hardware, clothing, and restaurants do NOT cost more in California, given that they are subject to the same level of regulation, the same labor markets, and high high energy costs.

I agree with one point of this paper: with electricity rates in California as high as they are, customers are less likely to shift from gasoline or natural gas for transport or heating. The electrification revolution will go better in other areas.

In Smart Rate Design for a Smart Future, we do propose that every customer should pay a fixed charge. A customer charge should cover the costs of metering, billing, and collection, about $5 – $10/month. And a “site infrastructure” charge should recover the costs of customer-specific distribution system investment — a share of the final transformer (typically shared with other customers) and the secondary service lines (shared in apartments; dedicated in single-family homes). For apartments, this is about $4/month, for single-family homes, about $10/month.

https://www.raponline.org/knowledge-center/smart-rate-design-for-a-smart-future/

That customer charge and site infrastructure charge should apply to every customer on the same basis, solar and non-solar. It would make bills for apartments a little lower, and those for single family homes (where nearly all of the solar panels are) a little higher. But it would better reflect cost causation.

Coupled with time-of-use rates for kilowatt-hours, this produces an efficient and fair rate design. Where the cheapest power is mid-day when solar is plentiful, such as in California and Hawaii, this lets solar customers enjoy the value of their solar production during the daytime, but then pay higher rates for power used in the evening or overnight, when they are dependent on the grid. In Hawaii, we found that the average solar customer would owe about $75/month with this type of rate design, even if they used a “net” of zero kilowatt-hours across a month.

The same smart rate design principles could work in California. There is neither a need nor a economic basis for collecting shared generation, transmission, or primary distribution costs in fixed charges. The most important role of utility regulation is to prevent the exercise of monopoly pricing power. That is, to enforce on monopolies the pricing discipline that markets enforce under competition.

When we go to the supermarket, the hardware store, or a clothing store, we bear the cost of “connecting to the grid” in our transportation costs locally; all of the costs of the global supply chains, including farms and factories, contain ships and distribution warehouses, plus the trains and trucks that bring Cheerios, pipe fittings, and underwear to our communities are built into the volumetric prices we pay for each item at the cash register.

That’s how real markets work. Yes, Costco charges a fixed annual membership charge. It accounts for less than 2% of their revenue. And we always have the option of going to Kroger, Walmart, or Target and avoiding the membership fee (and, indeed, small users — people living alone — normally do so.) Utility rates should recover a similar share of their revenue in fixed charges.

Come on Jim. No one is arguing to “preserv[e] the NEM status quo.” The industry has proposed meaningful reform.

I confirmed with Sean Gallagher that his “Come on, Jim” introduction in his comment was directed at the author of the blog, Dr. James Bushnell, and not at me, Jim Lazar. The adjacent positioning of Sean’s comment immediately following mine may have confused some people.

Like the major pro-solar participants in the docket, I favor changes to NEM 2.0. Their proposal in that docket to move from net-metering (retail rate credit for backfeed) to net-billing (value-of-solar credit for backfeed) is reasonable.

My own work focuses three essential principles of modern rate design, based on what happens in other, more competitive markets, which regulation is supposed to emulate:

1) Customers should be able to connect to the grid for no more than the cost of connecting to the grid. Shared primary distribution costs should NOT be included in the monthly fixed charge; only the customer-specific costs at the point of interconnection. That works out to no more than about $10/month for an apartment, and $20/month for a typical single-family home. A large single-family home with a dedicated transformer (or a rural customer with a dedicated transformer) would pay a little more. The current California IOU rates collect less than this amount. The Proposed Decision would collect more than this from solar customers.

2) Customers should pay for power supply and grid services in proportion to how much they use and when they use it. Time of use rates.

3) Entities providing power and services to the grid should receive full and fair compensation. No more and no less. NEM 2.0 in California as currently operated provides more than this; the Proposed Decision would provide less than this.