Why Are Major Credible Organizations Like ICCT, SBTi & IMO Getting Energy Demand Wrong?

The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and others share a common affliction, a belief that some demand segments are going to increase as they have for the past 30 years. As a result, their analyses are skewed.

Let’s start with the ICCT. They are an almost quarter century old Washington, DC headquartered think tank founded with good intentions and untainted money to focus on climate action in transportation, more than not. In the past few weeks, I’ve looked closely at their trucking, shipping and aviation analyses and found that they were deeply flawed. The trucking material put multiple thumbs on the scale for hydrogen, didn’t list the thumbs clearly in the same place, defended the thumbs as reasonable and required, and then quietly changed their conclusions and report to show the reality, that hydrogen trucking’s total cost of ownership was vastly more expensive than battery electric in every category.

Their maritime shipping material leans into liquid hydrogen which almost no major shipping concern is considering, lowballs its cost with a really basic mistake ignoring balance of plant and liquification costs, and adds rigid sails which are a rounding error technology, even putting them on vessel types that clearly aren’t appropriate for them. Their aviation material ignores center of gravity balancing of aircraft, civil passenger aircraft certification and battery energy density improvements to find that liquid hydrogen would be a great choice for the sector.

I traced their reports back to 2018, where they found that actually green hydrogen would be far too expensive as a transportation fuel, and then forward again through reports where they accepted obviously wrong projections of massive growth of transportation demand while simultaneously ignoring electrification’s role in massively reducing liquid fuel requirements.

The massive growth is due to accepting industry projections of continued compounded annual growth rates, something that the industry needs in order to have stock prices that aren’t plummeting and annoying their shareholders. Growth rates for aviation from IATA, Boeing and the ilk are clearly self serving and clearly wrong. Growth rate projections from ground vehicle fuel suppliers and internal combustion engine manufactures are clearly self serving and clearly wrong.

And on electrification, the ICCT has a bunch of molecules for energy types who just don’t grok electrochemistry and the radical improvements in battery energy density that are already commercialized, never mind the ones that are commercializing today. Vastly greater demand for energy and ignoring the biggest wedge in reducing the need for fuel will lead to absurd amounts of fuel requirements. That in turn leads to unnatural acts on the part of the ICCT, like finding that biofuels couldn’t possibly meet the actual demand, that electrification wouldn’t reduce demand and hence that green hydrogen must by definition be required.

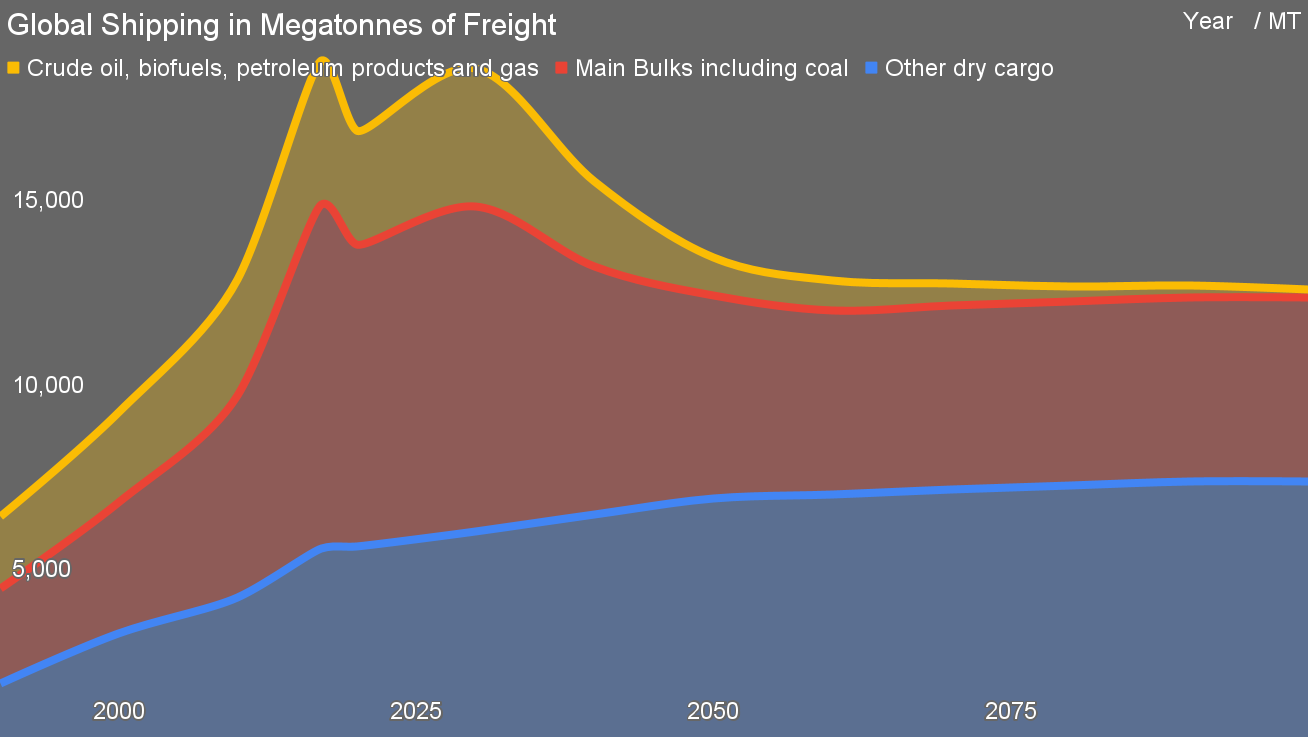

Are they alone? No. Enter the Science Based Targets initiative. That ‘science based’ is comforting, isn’t it. But science doesn’t do transportation tonnage projections. What does the SBTi say demand increases in shipping will be? Let’s look at the primary diagram that represents their data curves.

Notice anything strange about this? No?

Let’s start with tankers, one of the thickest segments. What do most tankers carry? Oil and natural gas. Is there any scenario in which oil and natural gas tonnages don’t plunge and climate change is addressed? No. The vast majority of tankers are going away over the next 30 years, not massively increasing in number and range.

What about bulkers, the thickest segment, which is differentiated by being dry bulks and shown as increasingly radically. Well, a huge percentage of that is coal. Is there any world in which coal shipping increases and climate targets are met? No.

Similarly, a large percentage of dry bulks are raw iron ore, mostly steaming to the same ports as bulk ships carrying coal. Those days are ending for four reasons. The first is that we have figured out how to reduce iron ore into iron and then make steel without coal, requiring methane which can come from biological sources, green hydrogen or even green electricity. The second is that China’s massive infrastructure boom is coming to an end, and with it their massive steel demand growth. Other markets for steel are growing much more slowly. Third, we’re scrapping increasing amounts of steel for new steel demand, with the USA at 70% already and that’s just going to increase. Finally, increased shipping costs with increased fuel costs for lower carbon energy are going to make more local processing more economically viable.

A full 40% of bulks and tankers are oil and gas. A full 15% of the combination is raw iron ore. Those tonnages are declining rapidly in the coming years, not rising. When 55% of the tonnage is in decline, the total tonnage isn’t going to be shooting up.

Why did SBTi get this so wrong?

The SBTi recognizes that different segments of the maritime industry (see more below on sector segmentation) may grow at different rates. For example, decarbonization across the entire global economy may be associated with reduced demand for oil transportation at the same time that increased global populations may be associated with increased demand for containerized cargo transportation. Therefore, assuming uniform growth across all segments of the maritime industry may lead to outputs from the maritime tool that are biased for or against certain segments of the maritime sector. While projecting transport demand at a segment-specific level could address this issue, the resources required to calculate these projections – and the host of assumptions that would need to be made to create robust and credible segment-specific demand projections – preclude the use of segment-specific demand projections at this time.

This translates to “It’s hard, we know it’s wrong, we can’t find shipping sources willing to give us better numbers and we aren’t going to stick our necks out.”

Okay, if their numbers are bogus and they know it but are unwilling to say so, where did they get their numbers? Well, from the International Maritime Organization (IMO), specifically its “Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020“. More specifically, page 223.

So the IMO, which is the UN organization with member states which care about shipping, is projecting a significant growth in shipping in every scenario, including the bulks and tankers that are going away. Seems as if they want this to be true.

They too have a source. The referenced paper is hiding a lot of people under et al, with over 40 authors. However, I sampled over half of them and found exactly none of them who had anything to do with maritime shipping or research related to it. I’m sure that they are wonderful people and diligent researchers, but like Vaclav Smil, they stay too far from the subject to get things right.

Who is Smil, you ask? He’s Bill Gates’ favorite analyst of everything, given to massive data analyses of absurdly broad sets of the economy. And he got three big things wrong about energy because he wasn’t close enough to the domain and didn’t ask the right questions. As a result, Bill Gates and many others were led down the wrong path. It took a long time for Smil to realize or at least admit one of his biggest errors, that he had fallen prey to the primary energy fallacy, and even then his paper on the subject didn’t say “I was wrong and here are the implications for everything I’ve ever published on the subject” it said “Look at this interesting thing over here”.

This is my heterodox projection of maritime shipping tonnage. It respects that oil, gas and coal shipping must diminish in any low-carbon world, along with the relative tonnage of those hydrocarbons. It respects that the world’s population is going to peak between 2050 and 2070 per the best demographic projections. It respects that China’s massive growth is at slowing. It respects that other developing economies won’t grow as fast as China did because they don’t have the conditions for that accelerated growth. It respects that container growth will continue, but doesn’t assume it will achieve the tonnage of departing bulks. And it respects that higher fuel costs will transform the ratio of local processing vs shipping raw materials.

Is my projection right? No, of course not. All I’ll commit to is that I think it’s less wrong than other projections. It’s less wrong than the projections the ICCT, SBTi and IMO are using, or at least I’m pretty sure it is.

So here we are. For the SBTi, seven years ago a bunch of generalists did some generalist stuff and didn’t ask what details were significant and got maritime shipping deeply wrong. I’m a generalist and I’ve made mistakes, so I recognize the pattern and am not judging, much. Then the IMO saw something it liked because it is a shipping organization, which was a continued growth of maritime shipping and confirmation bias led it to double down on it. And then SBTi saw it and didn’t have the courage to reject the nonsense projection because the IMO had published it and it was too hard to adjust it.

Let’s parse the cognitive failures. This isn’t meant to be harsh or judgmental but a learning opportunity.

The ICCT determined that hydrogen as an energy carrier would be vastly too expensive. So far so good. Then because they were mostly molecules for energy types, they rejected battery electrification for most modes of transportation. Then because they were mostly specialists looking for credible sources of data they accepted industry projections of massive transportation growth. Then because they were part of the same team that was being incented to promote each other’s work, they developed a tribal belief in each other’s number. The combination led them to manufacturing and then cherry picking the lowest cost numbers for manufacturing hydrogen. It was a collapsing set of dominoes that led to publishing really bad reports in three different transportation segments.

The SBTi is a different bunch of generalists. They cover an awful lot of ground, far more than the ICCT and even far more than I do, which is, to be completely transparent, saying something. I am very clearly a generalist, except that I’ve gone deep enough on a few domains to know that some things make sense and don’t make sense. I know less about SBTi than I do about the ICCT and the people in it.

But they leaned on the International Maritime Organization report, even though they were clearly uneasy with it. They didn’t have the courage to say “This is nonsense, let’s adjust it“. They should have. The IMO should have had the courage to say about the report they leaned on “This is nonsense, let’s adjust it” but it said things they liked to hear so they repeated them without judgment. They should have judged.

What are the lessons for all and sundry on this? They go back to my piece on accepting and adjusting for your own biases.

- If some piece of evidence makes you feel good that you are correct, be skeptical and validate the evidence.

- If some piece of evidence makes you feel uneasy, lean into the evidence and validate its provenance, facts and logic. Be willing to be wrong if the data shows that.

- If you are waving your arms over a broad domain, find people who will tell you which details are material so that your arm waving is directing an orchestra as opposed to merely flailing.

- If you suspect something is nonsense, have the courage to say so, adjust it and base your material on the adjusted version.

- If you were wrong in the past, own it, fix it and move on. Don’t double down.

The people behind these reports in many cases didn’t have the will and courage to do the above. And so the world is worse off. Our time to address climate change with fact-based, rational solutions has shortened.

Don’t be the people who produced these bad reports. Don’t let your team mates be them. Time is too short.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.