Voluntary Green Power to the Rescue?

Can the private sector lead on climate while Washington dithers?

Twenty-eight US states had heat advisories last week, temperatures topped 115 degrees in Texas and Oklahoma, and record heat waves in Europe dominated the news cycle. Meanwhile, the GOP-SCOTUS-Manchin axis of climate inaction has largely kept US federal climate policy on ice. Manchin’s about face last week makes it seem likely that the Biden administration will indeed get a climate spending bill in the end, but the bitter divide and halting progress in Washington leaves plenty of room for doubt as to whether federal policy is ready to match the scale of the climate crisis.

Fortunately, Washington isn’t the only locus of action here in the US. Bolder ambitions can still be found among not just vanguard cities and states like California, but also in a growing voluntary movement composed of diverse actors in the private sector.

According to Net Zero Tracker, more than a third of the companies listed in the Forbes Global 2000 now have a “net zero pledge.” The 300+ companies that are part of RE100, an organization aligning corporate action on renewable electricity, together procured 150 TWh of renewable electricity last year, which is equivalent to the size of the retail electricity market in New York state.

Corporate pledges clearly have real momentum. The real question is whether they are doing any good. Are they a sign of progress, or is this just the mainstreaming of greenwashing?

RECs: A Modern Form of Indulgences

A company that wants to reduce its carbon footprint might consider how to change its core business operations. This can be tough, especially if they don’t already have a system in place for measuring their own emissions.

A path of less resistance is to just keep doing what you are doing, but buy offsets (carbon reductions) to counteract your emissions. Carbon offsets come in several flavors, but to offset electricity emissions, a common approach is to buy Renewable Energy Credits (RECs). Each time a renewable power plant generates and sells one MWh of energy, it also generates one REC that can be sold separately from the energy. Infrastructure for establishing, verifying, and trading RECs already exists to serve Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) in many jurisdictions, so interested buyers have a ready market.

If a company wants to be “100% renewable,” it can tally up its annual electricity consumption from the grid, estimate the fraction that came from fossil generation based on their local grid mix, and then buy enough RECs to offset the dirty MWh they consumed. As such, RECs are to twenty-first century corporations what indulgences were to medieval sinners–an option to keep up your preferred lifestyle while wiping away the consequences with a quick financial transaction.

Compared to other ways to decarbonize a business, buying RECs is not just simple, it is also cheap. REC prices were long below $1 per MWh, meaning that they added minimal cost to energy bills.

(Several states have RPS requirements that specify a minimum amount of generation that must occur in that state. REC prices for these narrower markets can be much higher, ranging from $10 to $30 in a few states, with even higher prices for solar-specific RECs in some cases. Companies typically buy so-called national RECs that are produced outside of these specific locations and trade at much lower prices.)

RECs Can Lower a Company’s Footprint, But Do They Help Save the Planet?

Corporate pledges are measured and evaluated based on carbon accounting. When a company reduces its carbon footprint, it may or may not have any effect on global emissions because often all that happens is a reshuffling of responsibilities. Reducing one’s own footprint and reducing global emissions are simply different things.

A company’s procurement of renewable power only reduces emissions if it causes an increase in overall renewable generation (this is the so-called additionality problem). Such an effect is implausible for most REC purchases. Solar and wind farms built years ago, for example, still generate a REC every time they produce and sell an MWh. Buying up the RECs from those facilities typically won’t change how much they generate and thus has no impact on emissions. Such REC purchases just reshuffle paper claims about who “owns” a bit of electricity that was going to be generated regardless, making it a bit like buying an NFT for some image that we can all still share regardless of who owns it.

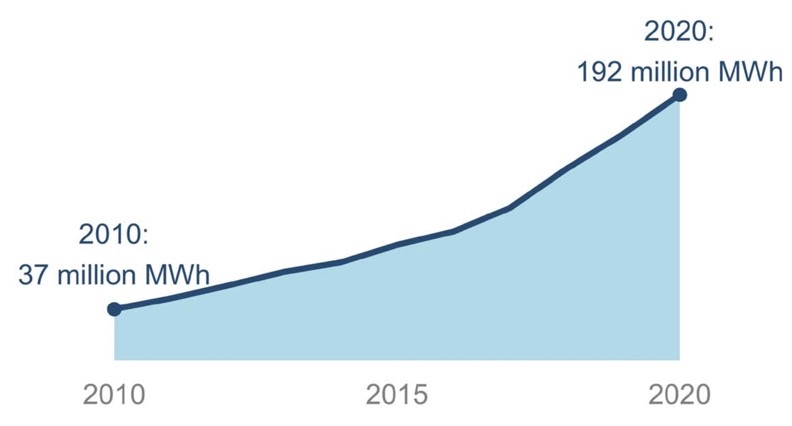

Voluntary green procurement can have an effect on emissions if demand is big enough to drive market behavior, for example by increasing overall REC demand and thus raising REC prices so much that it spurs additional development. The good news is that voluntary green power markets are now large enough to plausibly have such effects. NREL estimates that voluntary green power accounted for 192 TWh of power in the US in 2020, equivalent to 5% of all retail electricity. This is roughly half the size of the total compliance market for renewables across the nation’s patchwork of RPSs. Last fall, prices spiked to over $6 per MWh, signaling a potentially tighter market.

The Growth of Voluntary Green Power Procurement in the US

Even so, how much difference REC purchases might make it hard to assess with precision, and unless prices continue to rise, a healthy degree of skepticism seems appropriate.

Beyond RECs

Because of these problems with RECs, many have long pushed for voluntary procurement that goes beyond just scooping up whatever loose RECs a buyer happens to find in the market. Unfortunately, these alternative approaches don’t fully solve the core problem.

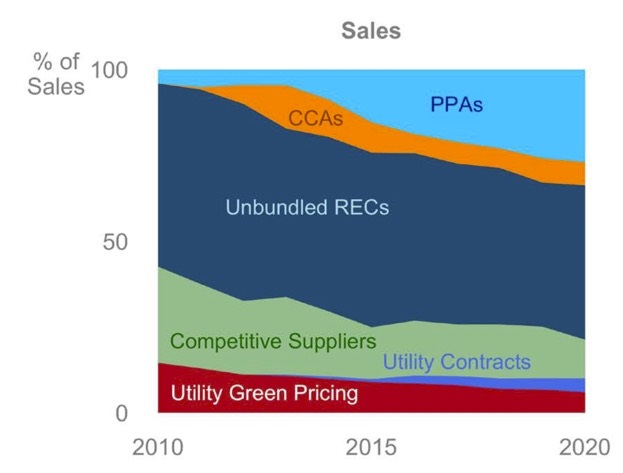

The second generation approach to clean power procurement is for companies to sign power purchase agreements (PPAs) with new renewable generation sources, usually for an extended number of years. Buyers pay for power and retire the associated RECs. PPAs, driven by corporate pledges, are a fast-growing share of the voluntary market, as shown below in another helpful chart from NREL.

Different Types of Voluntary Green Power As a Share of the Market

Some, led by Google, have gone beyond PPAs and advocated something called 24/7 clean power. In a 24/7 scheme, a buyer matches their load hour by hour within a local power market to clean generation. Advocates argue that this is necessary to substantiate a claim of running on 100% renewable energy. After all, if you simply have enough solar PPAs to offset your annual load, it still means that you are consuming fossil fuels at night.

Unfortunately, the emissions reductions implied by green power PPAs or even 24/7 clean power remains murky. If a company signs a PPA with a new plant, it doesn’t necessarily imply an emissions reduction because that plant might have found another buyer or might have been built even if the only option was to sell into the spot market, and most 24/7 schemes rely heavily on existing sources. As a result, in many, perhaps most, instances, even advanced green power procurement leaves a big gap between corporate claims and emissions reductions.

Voluntary Green Power: What is it Good For?

Despite my tone so far, I’m actually pretty excited about voluntary green electricity, so long as everyone involved understands the difference between corporate carbon accounting and actual mitigation. Companies that want to maximize their impact on emissions might pursue a different approach entirely, but I suspect most will continue to focus on their footprint with the goal of meeting pledges.

Companies following the standard path of green electricity procurement may not be maximizing their emissions reduction per dollar spent, but they are likely to create three key benefits.

First, given their size, growth, and signs of upward pressure on REC prices, it is highly likely that corporate clean electricity procurement is having some impact on renewable deployment, though how much is hard to say. A robust demand for PPAs is surely a good thing for wind and solar developers, and 24/7 buyers are sure to demand clean power at times and locations where it is currently absent.

Second, the push for 24/7 is a valuable experiment in thinking about what a truly renewable grid will look like, and how we might move towards it. Google and other proponents of 24/7 are explicit about this as a benefit–they want to start solving the implementation problems associated with a fully clean grid, and I for one am happy to have major companies out front on an issue that requires this type of innovation.

Third, and perhaps most important, is politics. Many companies have jumped onto the 100% renewable electricity bandwagon because it was easy and everyone else was doing it. But having made that commitment, they will now want clean power to be cheap and plentiful, which brings us all the way back to Washington. Voluntary clean power markets are never going to solve the climate crisis, but if they align an increasing share of corporate interests on the side of grid decarbonization, they could well have their biggest impact by pushing politicians and regulators to get green faster.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Sallee, James, “Voluntary Green Power to the Rescue?”, Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, August 1, 2022, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/08/01/voluntary-green-power-to-the-rescue/

Categories

James Sallee View All

James Sallee is a Professor in the Agricultural and Resource Economics department at UC Berkeley, a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, and a Faculty Research Fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Before joining UC Berkeley in 2015, Sallee was an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. Sallee is a public economist who studies topics related to energy, the environment and taxation. Much of his work evaluates policies aimed at mitigating greenhouse gas emissions related to the use of automobiles. Sallee completed his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Michigan in 2008. He also holds a B.A. in economics and political science from Macalester College.

You may wish to better educate yourself on RECs by reviewing some of the literature, such as: https://bit.ly/WeinsteinRECsArticle

Mark,

I appreciate your comments. I was on the first advisory team for LevelTen Energy, which is building a market for long-term RE PPAs. I love the evolution of this market. Bryce Smith, who runs Level Ten, worked for me at the Bonneville Environmental Foundation back in the 2000s. We closed the first retail REC deals in history there.

I am a huge fan of the market evolution. *And* I think unbundled RECs are a fine participant in that market as long as they are Green-e certified. Many, many organizations do not the bandwidth or the balance sheet to sign long-term REC deals. The notion that developers will build projects on spec is not a sign the market is broken, it is a sign that it works. Bashing those projects and their buyers undermines a functioning market for the things we *want.*

My issue is the insistence on the “perfect” (which often isn’t) rather than the “plenty good enough.” These purity tests pit allies against each other. We have a crisis on our hands. We need to stop arguing around the edges.

You equate renewable energy purchases with offsets. They are not the same. See for instance https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-03/documents/gpp_guide_recs_offsets.pdf.

Energy codes and standards are beginning to require a minimum amount of on-site renewable energy (even though this is not popular at Haas). Some of these codes allow the purchase of off-site renewable energy (but not offsets) when on-site renewable energy is not feasible. This approach has been implemented in Architecture 2030’s ZERO Code and the International Green Construction Code (ASHRAE 189.1). It is currently being considered for the IECC, which is the energy code for most of US states.

The codes require that off-site renewable energy purchases meet three minimum requirements: (1) the RECs must come with the deal, (2) The transaction shall be durable and live with the building, and (3) the generation source must be “eligible” (can’t count legacy hydro plants or other “old” RE projects, for instance). But even then, not all RE procurement methods have equal impact (you call it additionality). If the project is located in a dirty grid, the avoided carbon is greater. Virtual or financial PPAs require large purchases and are limited to organizations with deep pockets. The most accessible options are community solar and green retail pricing, but it is easy to opt out of these programs and durability is hard to achieve. Some of the codes discount RE purchase options that are considered to have less impact. Unbundled RECs are commonly discounted, since they are commonly underpriced. But, not all RECs are the same. For each REC, we know where the generator is located, who owns it, whether it is wind or solar, its nameplate capacity, the year it started producing energy, and the month and year when the renewable energy backing the REC was produced. When conditions or restrictions are placed on the purchase of RECs, their impact increases along with their price.

I appreciate your blog and the work at Haas, but I agree with Rob Harmon that your reference to indulgences is unfair. With the inability of the federal government and most state governments to effectively address climate change, installing on-site RE or buying off-site RE is an option that most of us have for doing something. Let’s applaud those efforts, not degrade them.

I’m going to encourage you to up your game on this topic. Your piece starts out with all the old, fully debunked arguments about additionality and turns people off to an important market by bringing up the silly analogy to indulgences.

I live in Washington State, which has an RPS standard. I buy voluntary RECs. If I stop buying those RECs, the utility will use them for their RPS compliance. My purchase is a game of “keep away” with the utility. My purchase forces the utility to build or procure new renewable energy (or RECs). That is the “additionality” that so many critics ignore.

If we take the argument on financial additionality to its logical conclusion, all apples should be free because the apple trees were planted long ago. Renewable energy projects are built using project finance principles. The value of the RECs in future years are part of that math, in the same way future apple sales are part of the “apple tree” math. In addition, what does the owner of the facility do with “extra” money you think they get and perhaps do not deserve? Well, they use it to do more of that they do – build renewable energy projects. If their projects are profitable, they can build more projects. Do we want their projects to be less profitable than fossil projects?

In addition, RECs are not an indulgence. That is just a cheap shot. Back in the days of church control, buying indulgences was a way for wealthy people to NOT take responsibility for what they did. The indulgence payment had no relationship to the “sin.”. REC purchases are precisely the opposite of that. RECs are used to match the consumption of electricity with a requirement that an equal amount be provided by renewables. That is called taking responsibility for the source of your energy. What is the alternative? Living in a cave? What is gained from bashing the folks who are trying to take responsibility for their energy consumption? Why not bash the companies that are making no commitments?

I fail to understand why, given that REC purchases make renewable energy projects more profitable and hence, more attractive as investments, your blog post frames the entire discussion in a way that does nothing but make it harder to do the very things we need to do to save the climate. I would urge you to use your skills and position to bash fossil fuels instead.

If we adopt the approach the beginning of your piece encourages, and throw up our hands, we leave all the power to move the market to the government and utilities. Why on earth would we undermine the market as a lever?

I appreciate that you transitioned your argument at the end. But why bother with all the worn out, debunked arguments in the first place?

Rob,

I found the post to be well balanced with lots of links provided to delve further into nuance positions. If you haven’t already taken a look at the approach Google is taking I recommend doing so as an REC that isn’t tied into the needs of the demand of users of energy to do work is leading to way to much curtailment from my perspective (our PV system started providing kWh’s to the grid on 7/24/2006),

Not giving credit to nuclear energy for it’s co2 free output can partly be blamed for the mess in Europe currently.

Mark

PS The prices for California emission credits increased in early 2022 auction-

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=51918

Mark

Note that CARB GHG allowances are not the same as renewable energy credits (RECs). Those allowance prices are driven by scarcity in alternative direct GHG mitigation measures.

The REC price calculated as part of the PCIA exit fee for electric utilities has been declining steadily over the last decade as the differential between renewable and convention generation has disappeared.

I am a net generator with my rooftop solar panel system but only get about 3 cents per kilo watt hour at “true-up”. Who is getting my REC for that excess generation? As solar becomes more affordable and battery storage make homes less grid dependent, will REC credits mean anything? I had so much extra power last year, I turned off my gas furnace and ran all electric heaters throughout my home because it was cheaper with the 3-cent “true up” electricity than the overpriced natural gas.

20 years ago emergence of a healthy voluntary RE market was a big deal in Calif utility and legislative arenas. That public demonstration of support is just as necessary today in other parts of US and is still important even in CA. At Green-e we strive to maintain public confidence that their voluntary purchase carries addionality; a difficult task as RPS’s, CCA’s, and REPPA’s become more ubiquitous, but we CAN continue to do that because we care and we know renewables.

Bud Beebe

Chair, Green-e Governance Board