Can Targeted Tax Credits Bring Clean Energy to Coal Country?

The Bidenomics of place-based climate policy.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is a big climate deal. At the heart of this deal are billions of dollars in clean energy tax credits. Precisely how many billions is hard to know. Recent estimates are in the range of $780B to $1,070B over the next decade.

Many of us will benefit significantly from this kind of federal investment. Accelerated clean energy deployment will help us avoid the most damaging impacts of climate change. Reduced fossil fuel combustion will reduce exposure to harmful air pollution. And billions of dollars of clean energy investment will generate employment opportunities and profits in more sustainable energy sectors. All good!

But not all are on the winning side of the clean energy transition. In particular, communities built on a bedrock of fossil fuels extraction, processing, and production stand to lose.

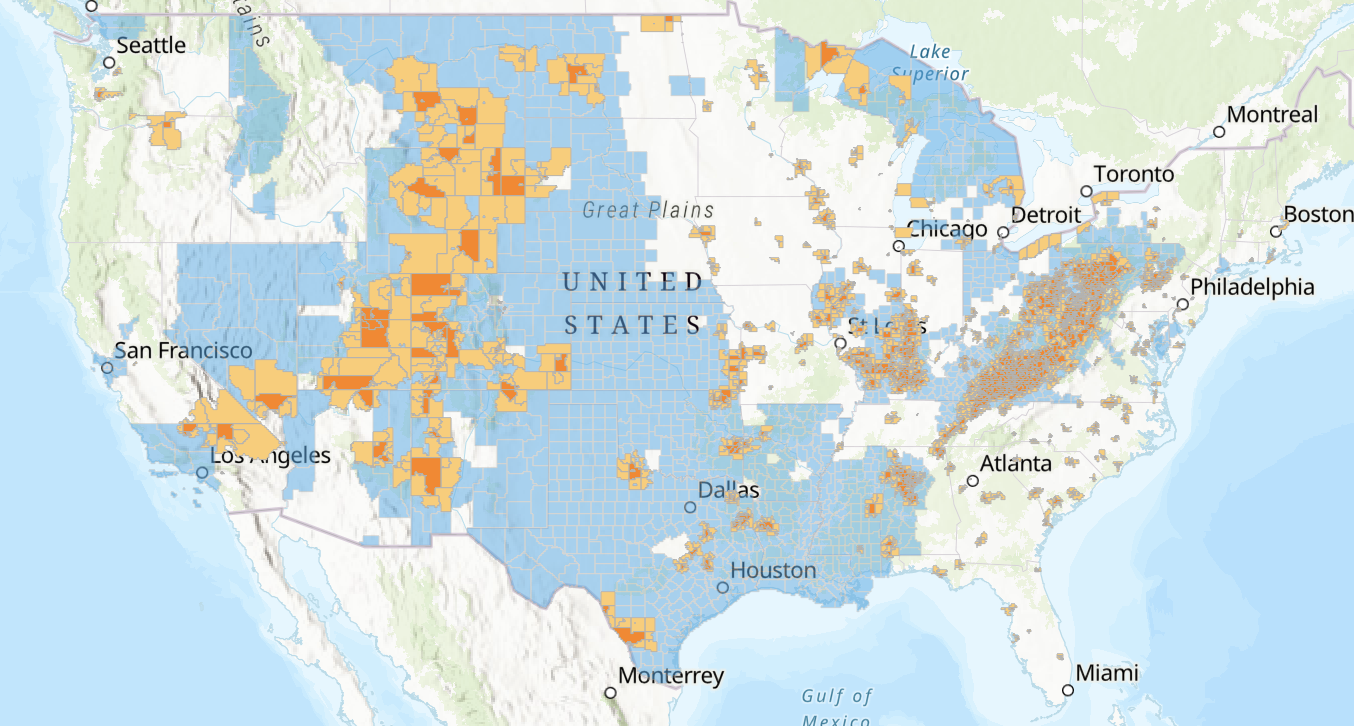

From day one, President Biden has been promising coal communities that they will not get left behind. As part of that promise, the IRA includes tax credit incentives that are designed to catalyze clean energy investments specifically in communities that have been dependent on the fossil fuel industry. The Treasury Department recently mapped out the “energy communities” that will be eligible for these credits (and other incentives).

Offering targeted tax credits to clean energy projects in energy communities is a Bidenomic idea worth unpacking. This week’s blog post digs into the whys and the hows of these “place-based” clean energy incentives.

The canary in the coal decline

If we want to support energy communities through this clean energy transition, we’ll need to anticipate the challenges they will face. A new working paper that Energy Institute alum Josh Blonz has co-authored with Brigitte Roth Tran and Erin Troland takes a careful look at how recent declines in coal demand are impacting energy communities in Appalachia.

Between 2011 and 2018, Appalachian coal production fell by more than 40%. But coal mining accounted for only 2% of regional employment in 2011. So you might think that the economic impacts of this coal decline would be limited to the small share of households that are directly employed in this industry.

Josh and co-authors track multiple measures of households’ financial well-being: credit scores, delinquencies, and transition into bankruptcy. They find that decreased demand for local coal production has negatively impacted all outcomes they consider. The graph below shows the estimated impacts of declining coal demand on credit scores at different points in the credit score distribution. One important finding is that these impacts extend well beyond those who held coal industry jobs.

These are canary-in-the-coal-decline impacts insofar as they are leading indicators of much larger problems. Indeed, past research has found that longer run impacts of job loss can be devastating in slack labor markets. In other words, substantial hardship could lie in store for America’s energy communities.

Will clean energy investments flow into coal country?

Looking ahead, we might hope that the IRA will catalyze billions of dollars of green investments in energy communities to help rebuild and revitalize. Absent deliberate efforts to direct investments into these places, I think this is unlikely to happen.

States have a huge role to play in determining where the IRA resources ultimately go. There are billions of dollars of clean energy tax credits on the table. But it is up to states and local governments to proactively go after these incentives. This requires administrative capacity and political will.

So far, the states that seem most motivated to attract these federal dollars are those looking to “supercharge” their state-level climate actions and ambitions (e.g. California, Maryland, and New York). Meanwhile, some energy communities seem to be leaning in the opposite direction (e.g. North Dakota and Wyoming).

The upshot: limited administrative capacity, together with some fraught energy politics, could seriously slow the flow of clean energy investments into the energy communities that could really benefit.

What’s the deal with place-based tax credits?

The IRA will soon offer more generous tax credits for renewable projects in energy communities. Developers can receive a bonus of up to 10 percentage points on top of the Investment Tax Credit and an increase of 10 percent for the Production Tax Credit. This is in addition to federal loan guarantees and infrastructure spending programs that are earmarked for these places.

I will leave it to the public and labor economists to weigh in on whether this kind of place-based climate policy can succeed in revitalizing distressed energy communities. What is clear is that the existing safety net is ill equipped to address the burden of job loss and industrial decline in these regions, and placed-based experiments of this sort can be helpful.

As an environmental economist, I see two additional benefits worth highlighting.

The first benefit is environmental. Under the pre-IRA tax credit model, tax incentives subsidized all renewable energy projects at the same rate, regardless of whether these resources displace natural gas or coal. Offering more generous subsidies for investments in coal communities will conjointly offer larger incentives to projects that displace more greenhouse gases per MWh.

The maps below help to show that coal communities are located in parts of the country with relatively coal-intensive – and thus carbon-intensive- electricity generation. A wind turbine in California is displacing about 0.18 tons of GHG per MWh on average. Move that turbine to West Virginia, and it would displace 0.88 tons/MWh!

Another potential benefit is political. The vote share map below reminds us that many energy communities are located in deeply red states. Nudging clean energy projects into these areas is not going to turn a red state blue. But it could improve the durability of Biden’s climate agenda if likely opponents see tangible benefits in their communities.

Learning by doing

Targeted tax credits have the potential to deliver meaningful economic and environmental benefits to energy communities. Experimentation with this idea is just getting underway. Current proposals are imperfect. There are important concerns being raised about how much of the country currently qualifies as energy communities under the currently proposed criteria, and what additional steps we should be taking to ensure these incentives are effective. There will be learning by doing. But this is learning we need to be doing to ensure the clean energy transition is effective, equitable, and durable.

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith, “Can Targeted Tax Credits Bring Clean Energy to Coal Country?”, Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, May 22, 2023, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2023/05/22/can-targeted-tax-credits-bring-clean-energy-to-coal-country/

Keep up with Energy Institute blog posts, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Categories

Source

Source

One element of the IRA’s clean energy investment plan which cannot be overstated (in my opinion) is the unwillingness of many state governments to proactively pursue clean energy tax incentives, specifically for partisan reasons. In today’s ultra-polarized political environment, conservatively-controlled state governments have displayed a blatant willingness to sabotage federal programs which are perceived as Democrat-led. A perfect example of this is Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which offered enormous federal funding incentives for states to expand Medicaid. These funding incentives have been available to states for over thirteen years, yet Medicaid expansion has still not been adopted by ten Republican-controlled states (https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/3914916-these-10-states-have-not-expanded-medicaid/).

A recent paper by Alexander Hirsch and Jonathan Kastellec discusses this phenomenon with “a theory of policy sabotage” (https://doi.org/10.1177/09516298221085974), in which “the deliberate choice by an opposition party to interfere with the implementation of a policy can be an effective electoral strategy, even if rational voters can observe that it is happening”. This strategy has been utilized with alarming success over the past decade, and it provides an extremely strong incentive for Republican-led state governments in coal country to obstruct transition efforts. From a partisan perspective, the political incentives of sabotaging the clean energy transition can outweigh the economic incentives of committing to the transition in good faith. My worry is that this will result in underutilization of the IRA’s green investment funds and transition resources in many deep-red states where they are most needed, and at that this underutilization will be to the detriment of energy communities and the rest of the country.

Srivastav and Rafaty provide a broad road map for clearing this hurtle in “Political Strategies to Overcome Climate Policy Obstructionism” (https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722002080). They identify five political strategies with which the climate movement can “compete against entrenched hydrocarbon interests”, including appeasement (compensating the “losers”), co-optation (working with incumbents), institutionalism (changing public institutions to support decarbonization), antagonism (creating reputational or litigation costs to inaction), and countervailance (making low-carbon alternatives more competitive). These strategies have varying levels of viability depending on the economics and social environments of individual states, but one thing is clear: the success or failure of the clean energy transition will be as dependent on politics just as much as policy.

Fortunately, to the best of my knowledge, the IRA tax credits do not require any complementary fiscal or administrative action by states for taxpayers to obtain federal tax credit benefits. However, the IRA also offers numerous grants, loans and other incentives that, at the very least, will not be optimized — or perhaps not even utilized at all — without state and/or local action, as the ACA experience has shown. Political obstruction surely has been and will continue to be a significant factor in our clean energy transition. Thanks for highlighting these issues.

One element of the IRA’s clean energy investment plan which cannot be overstated (in my opinion) is the partisan unwillingness of many state governments to proactively pursue clean energy tax incentives, specifically for partisan reasons. In today’s ultra-polarized political environment, conservatively-controlled state governments have displayed a blatant willingness to sabotage federal programs which are perceived as Democrat-led. A perfect example of this is Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which offered enormous federal funding incentives for states to expand Medicaid. These funding incentives have been available to states for over thirteen years ago, Medicaid expansion has still not been adopted by ten Republican-controlled states (https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/3914916-these-10-states-have-not-expanded-medicaid/).

A recent paper by Alexander Hirsch and Jonathan Kastellec outlines “a theory of policy sabotage” (https://doi.org/10.1177/09516298221085974), in which “the deliberate choice by an opposition party to interfere with the implementation of a policy can be an effective electoral strategy, even if rational voters can observe that it is happening”. This strategy has been utilized with alarming success over the past decade, and it provides an extremely strong incentive for Republican-led state governments in coal country to obstruct transition efforts. My worry is that the political incentives of sabotaging this clean energy transition will outweigh the economic incentives of utilizing the green investment funds made available by the IRA, even if this obstruction comes at the detriment of their constituents and the rest of the country.

Srivastav and Rafaty provide a broad road map for clearing this hurtle in “Political Strategies to Overcome Climate Policy Obstructionism” (https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722002080). They identify five political strategies with which the climate movement can “compete against entrenched hydrocarbon interests”, including appeasement (compensating the “losers”), co-optation (working with incumbents), institutionalism (changing public institutions to support decarbonization), antagonism (creating reputational or litigation costs to inaction), and countervailance (making low-carbon alternatives more competitive). These strategies have varying levels of viability depending on the political environments of individual states, but as unfortunate as it may be from an environmental economics perspective, the clean energy transition cannot be driven with price signals alone.

“Offering more generous subsidies for investments in coal communities will conjointly offer larger incentives to projects that displace more greenhouse gases per MWh.”

Yes, in addition to the bigger bang for the buck in GHG reductions that Meredith notes, offering greater incentives for “energy communities” mitigates one of the great efficiency and equity challenges with tax incentives: that is, inevitably governments end up paying someone (or firm) through a tax credit for an investment that would’ve been made anyway — for example, the Tesla buyer in Atherton. Clearly there is more need of and potential benefits from IRA tax credits in those targeted communities. And because these are federal tax credits, the administrative efforts for state and local jurisdictions should be minimal, but, as Meredith pointed out, the political will to pursue these incentives there can be much trickier.

As for the negative impacts of “accelerated clean energy development,” Meredith correctly notes that “substantial hardship could lie in store for America’s energy communities,” and the working paper she cites provides clear evidence of that. But another dynamic needs to be considered here: Job training — or “retraining” — for clean energy jobs.

Shortly before Biden’s top climate adviser, Gina McCarthy, left her job last year, she asserted that many workers have “relied on a fossil-fuel based system for nearly 200 years,” and “reshaping the system” creates an obligation to give these workers the “training and resources to build the clean energy economy.” But that’s far easier said than done. Most, though far from all, jobs in the fossil fuel industry are unionized and have been for decades, reaching an apex in the 1950s and 1960s, when, as John Kenneth Galbraith famously observed, labor effectively served as a “countervailing power” to business. Those days are, of course, long gone, but there still is a vestige of that dynamic in private sector union jobs. The fact is, one cannot easily leave a job in coal, gas or oil for a commensurate “green” job, very few of which are unionized, and expect the same pay and benefits package. Assessing the strength of the safety net for those who lose fossil-fuel jobs doesn’t change the fact that they are falling. And so far these training/retraining efforts have had modest success at best.