What’s the Plan for Carbon Pricing in California?

Policymakers see a diminished role for California’s cap-and-trade program.

November 14, 2012 was a big day in my book. This was the day we welcomed my son into the world (cutest boy ever). This was also the day that launched California’s carbon market with the inaugural GHG allowance auction (a sell-out success).

Source: Alamy

The baby boy is now a high-energy nine-year-old. With every milestone, we’re learning how to give him room to grow. California’s cap-and-trade program has also grown smarter over the years. But policymakers seem reluctant to give this maturing market more room and responsibility.

This reluctance is spelled out in the draft Scoping Plan released last week. Every five years, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) takes stock of the state’s progress toward its climate goals. Once approved, these plans shape the high-stakes process of updating California’s climate policies and programs.

Last week’s release of the draft plan kicks off a 45-day public comment period. If you care about California’s climate policy, now is the time to read and think and question this plan. After a first read, here’s my concern. I can see why regulators might be inclined towards more prescriptive regulations. But as our climate ambition escalates, casting the carbon market in a diminished role will cost us.

Before unpacking this argument, I should emphasize that all opinions and bad parenting metaphors are my own. The views in this blog should not be attributed to my esteemed Independent Emissions Market Advisory Committee (IEMAC) colleagues.

California Climate Policy 3.0

The scoping plan starts with a projection of what California’s GHG emissions trajectory will look like under the many prescriptive regulations/ mandates/ orders that are already on the books. The blue line in the graph below charts this “reference” scenario. This emissions trajectory reflects all existing climate policies and programs *except* the carbon market.

Source: 2022 Draft Scoping Plan

California has committed to reducing GHG emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 (~260 MMT CO2e). This 2018 executive order set a more ambitious goal of carbon neutrality by 2045. Focusing on the legally binding 2030 target, you can see that the reference scenario falls short.

The scoping plan goes on to identify additional measures (e.g. accelerated building electrification, carbon capture and storage) that could be deployed to bring California GHGs in line with our targets. The green line projects emissions under a proposed set of additional measures and investments.

Just because additional measures could be deployed to reduce our GHG emissions does not mean they should be mandated. We could alternatively choose to rely on the carbon market to fill the gap between the reference scenario and our GHG targets. But this is not the vision articulated in this Scoping Plan:

“…the Cap-and-Trade program will likely play a reduced role depending on how uncertainties play out and if new prescriptive policies or legislation is introduced”.

We have built a world-class, economy-wide cap-and-trade program in California. Why are we planning to ask less – versus more—of this carbon market?

(A rhetorical question. There are political reasons to ask less. But today’s focus is on why we should be asking more…)

A diminished role for carbon pricing will cost us

Carbon pricing is not a silver bullet. For a variety of reasons (network externalities, information failures, leakage concerns, dynamic efficiency considerations, etc.), we need a portfolio of policy approaches to confront the climate crisis. But after a decade of choosing prescriptive policies over carbon pricing, it’s clear that this choice can have significant cost implications.

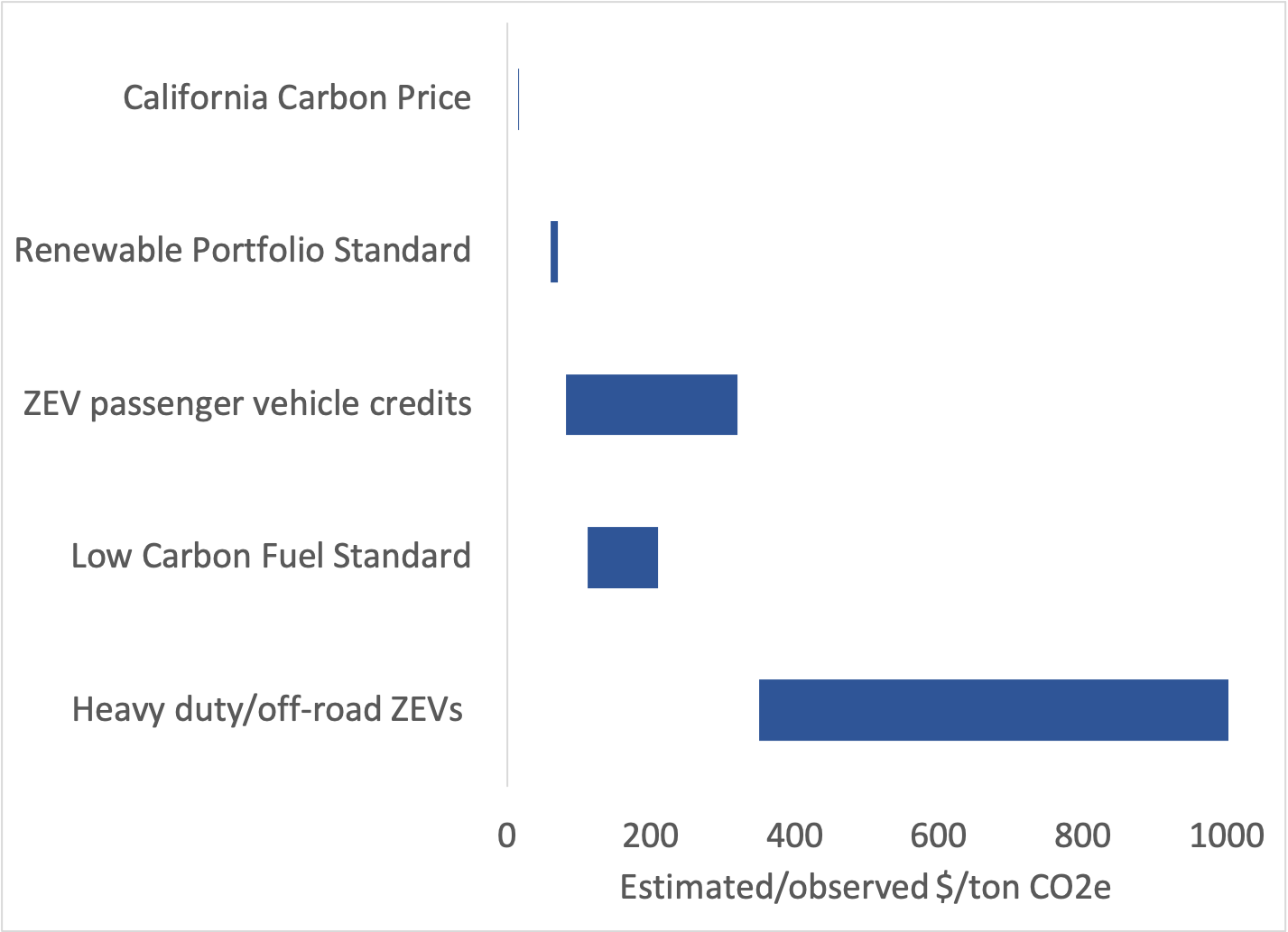

The cost per ton of CO2e emissions avoided is one coarse metric we can use to compare climate policies and programs. The graph below compares an assortment of cost-per-ton estimates (some marginal, some average) that have been recently observed or estimated.

Notes: I built this graph from the following sources: GHG allowance prices (2018-2020) are reported here. LCFS prices (2018-2020) are reported here. Cost estimates for the RPS in 2018 are from this LAO report. Cost estimates for the ZEV credit program are estimated here. Cost estimates for heavy-duty ZEVS are from this LAO report (other ZEV program costs estimated in this report are off the chart).

The graph shows that the costs of the prescriptive programs and mandates have been higher than what we’ve been paying for GHG allowances in the carbon market. Mandating some relatively expensive measures has put downward pressure on allowance prices, leaving relatively inexpensive abatement options in the economy-wide carbon market unpicked.

It’s important to note that these are not apples-to-apples policy comparisons. There are other benefits (e.g. local air pollution reductions) that could vary across abatement options but are not captured in cost/ton numbers. We should be willing to pay more for organic-fair trade-vegan apples. But when we choose a relatively expensive apple, we should be asking if the additional benefits justify the higher price.

The carbon market backstop

Once approved, California will start designing a policy strategy to support the scoping plan vision. This is where the carbon market could have a critical role to play (if we let it). If/when measures proposed in the scoping plan turn out to be more expensive or less effective than CARB has projected, policymakers will have to decide whether to stick with the plan or come up with an alternative.

One alternative: ask the carbon market to seek out more least-cost GHG reductions. To ready the carbon market for this backstop role, there are some concerns that we need to tackle head-on.

One concern pertains to the size of the allowance bank. Market participants have banked more than 320 million allowances over the last nine years. A bank of this size could undermine efforts to hit our targets if, when we ask the market for GHG reductions, market participants respond by drawing down the bank.

How many allowances is too many in this market? My household has saved a significant share of our earnings over the past decade. If we cease to exist in 2030, we are over-saving. But we’re putting money in the bank today in anticipation of a post-2030 future in which we’re spending more (two kids in college!) and earning less (we might retire someday). Bringing it back to the carbon market, I think it’s hard to assess the over-supply problem when no formal commitments have been made to allocate permits –or extend the program– past 2030.

CARB has an obligation to “evaluate and address concerns related to overallocation” of available allowances for 2021 through 2030. IEMAC has identified approaches that could be used to adjust allowance supply. We need to tackle concerns about allowance supply as we ramp up our climate ambition. At the same time, it will be important to extend the time horizon of the carbon market to align with the horizon of our policy goals.

Asking more of the carbon market

California policymakers are being asked to meet ambitious climate goals in the face of boundless uncertainty. They are also tasked with charting a path to carbon neutrality that is equitable, affordable, politically palatable, and exportable to other jurisdictions. Given the complexity of this exercise, it makes sense to plan ahead. But there is a risk of becoming too wedded to the plan.

It will be important to devise a policy strategy that is smart and flexible and capable of responding to new information/new innovation. This is what carbon markets are born to do. If we give it a chance, California’s cap-and-trade program can do more to find and deploy relatively low-cost GHG emissions reductions. If we are serious about cost containment, we should be putting this carbon market to work.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas.

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith, “What’s the Plan for Carbon Pricing in California”, Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, May 16, 2022, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/05/16/whats-the-plan-for-carbon-pricing-in-california/

Categories

Meridith I just saw a computer simulation where a $200 per ton carbon tax made no difference in the optimum plan for a Eurpoean country heavy into coal. The optimum plan with or without the tax was a lot of nuclear base load generation with some gas load following and a small amount of battery storage. I said to the modeler that plan is no good because it still requires a lot of gas, which is mostly available if you want to get in bed with Russia, which is not a good option. We need a nuclear load following plan that accommodates more wind and solar to displace nuclear energy. The plan does not het exist and a carbon tax isn’t going to lead to a carbon free system because the carbon price will never be made high enough to force this to happen.

Is there any strong statistical evidence linking cap-and-trade with reductions in GHG emissions? I know British Columbia’s fee-and-dividend scheme has shown conclusive results, but it’s not carbon pricing as much as a revenue-neutral carbon tax.

Seems the only way these cap-and-trade measures get passed is when they can be manipulated to reward consumption of fossil fuels – in terms of achieving their intended goal, they’re worse than nothing. And it seems the degree to which they’re carefully-thought-out is positively correlated with how much worse-than-nothing they become.

I may be wrong, but what I find truly bizarre is that fuel-combustion emissions from residential and commercial buildings are *not* covered in California’s cap-and-trade market. Continuing to protect the greater population from climate change pricing (I’m guessing for political reasons) and not making the cost of these emissions salient in their decisions seems like a bad strategy given the state’s aggressive desire to want building owners to switch from using fossil gas to electric. Adding carbon pricing to fossil gas consumption would increase the cost-effectiveness of electrification efforts and the added revenue could accelerate efforts in helping the most vulnerable energy-burdened residents.

Nevermind. Residential and commercial customers are subject to cap-and-trade pricing. https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/climatecredit/

Not sure if it is salient enough though!

Nick, California’s climate credit is a joke. In 2021 PG&E credited customers $17, or 2.5% of the average residential gas bill ($660). And climate-conscious customers aren’t incentivized to do anything when most of their electricity is generated by burning gas anyway.

Yesterday the Dept. of Energy extended the deadline for PG&E to apply for a piece of Biden’s $6 billion nuclear power plant credit to July 5 – at PG&E’s request. Renewing Diablo Canyon’s license, aka, acknowledging nuclear must play a role in decarbonizing California’s grid, would provide more incentive to electrify than any token handout from PG&E or Sempra.

Nick

The gas & electric utilities were provided free allowances that they could either use or sell in the CARB auction. The auction revenues are rebated twice a year to customers. The opportunity cost of these allowances is reflected in how the electric utilities dispatch their resources and the CAISO calculates how much it adds to the wholesale electric price. But I’m not if these allowance prices have any impact on residential and commercial gas prices, especially since the allowance revenues are rebated and the gas utilities don’t have to purchase them in the first place. It’s as though CARB thought it was designing a zero-revenue auction system but forgot to include the opportunity cost side to the initial allowance holders.

Thank you, Richard. I had a feeling that there was some sort of market design issue that created my confusion.

Another good article from the Haas energy blog. It is important to emphasize the cost per tonne of reduction and make sure that any revenue from the carbon trade goes to the lowest cost of reduction. For example, as I have mentioned before, spending part of the cap-and-trade revenue on California’s high-speed rail https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/4252#:~:text=The%20high%2Dspeed%20rail%20project%20receives%20about%2025%20percent%20of,is%20available%20for%20the%20 project has resulted in tons of carbon dioxide release from the concrete poured. All this on a project that has no realistic possibility of being finished, let alone being a cost-effective way of carbon reduction. To be effective, cap and trade funds must be spent on the lowest cost carbon reduction. In the United States annual carbon emissions are about 15 tonnes/person. https://www.worldometers.info/co2-emissions/us-co2-emissions/#:~:text=CO2%20emissions%20per%20capita%20in,in%20CO2%20emissions%20per%20capita. At a cost of $100/tonne that is a cost of $1,500 per person, or $6,000 annually for a family of four. This will be a very difficult politically, and any reduction strategies over this cost should be disregarded at counterproductive. This means that strategies such as the ZEV passenger vehicle credits shown in the graph in this article should be discontinued in favor of lower cost alternatives. Fortunately, there are still many ways of reducing carbon emission, with many energy saving technologies being so cost effective as to save costs even while reducing greenhouse gas production https://www.mckinsey.com/about-us/new-at-mckinsey-blog/a-revolutionary-tool-for-cutting-emissions-ten-years-on. To be most effective, any cap-and-trade program should be putting any revenue back into the most cost-effective reduction methods. As this is so politically difficult that it has so far failed, rebating the revenue to taxpayers in the form of the carbon fee and dividend may be the most cost-effective way of reducing carbon emission. This will also blunt the effective of higher prices on lower income groups.