What’s Not Crushing California Rooftop Solar?

Bill savings from residential PV are as large now as a few years ago, but the industry is facing other big challenges.

2019 was a good year for residential solar in California. In the service territories of the three large investor-owned utilities – Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric – the industry installed over 800 MW of capacity, up 14% from the prior year. The industry leader, SunRun, saw its stock price rise nearly 40%. The California Solar & Storage Association (CalSSA) celebrated hitting 1 million solar rooftops in the state and their annual report gleamed with optimism.

Fast forward to today and the media is filled with articles about the catastrophic decline of the industry. Most of the blame centers on the change in compensation for electricity that solar homes sell to the grid, which was implemented last April. CalSSA is shouting from the apparently barren rooftops that the California Public Utilities Commission is driving a stake through the heart of the industry with this policy shift.

(Source, but altered by the author)

But a closer look at that policy change – as well as the recent eye-popping residential rate increases – leads to a very different conclusion.

Every household that got a permit for a new solar system prior to April 15, 2023 locked in credit for its electricity generation at the retail electricity rate, under what was known as “NEM 2.0”. Systems permitted after April 15 are covered by “NEM 3.0”. They receive a much lower rate when the household exports electricity to the grid, but these customers still save the full retail rate when the power is used on site.

That last detail is important, because when you do a little math, it turns out that the bill-savings incentive to install solar today under NEM 3.0 is about the same or greater than it was for most households in 2019 under NEM 2.0.

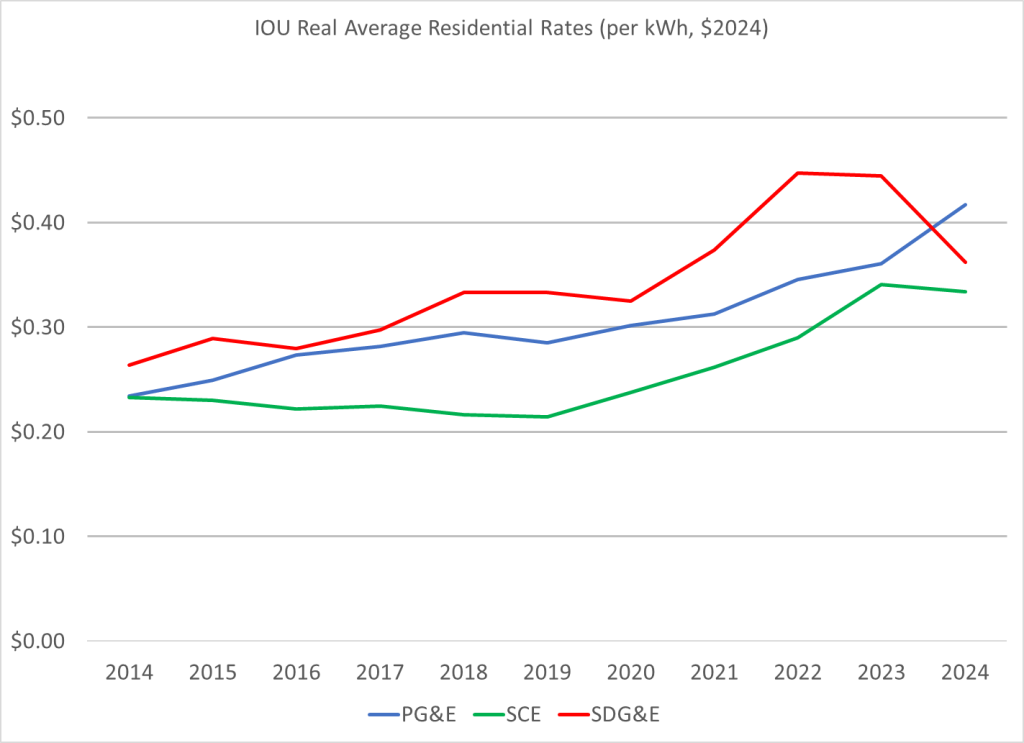

How could that be? Well, even without a battery, the typical solar household exports about 50% of its rooftop output to the grid (the Solar Energy Industry Association says it’s 20%-40%) . So, while the new policy cuts the value of exports, the higher retail rates greatly increase the value of the electricity used on site. Here’s a link to my calculation spreadsheet. Even at a 50% export rate, it indicates that the solar incentive is slightly higher in 2024 than it was in 2019 for SCE and PG&E customers. It’s about 38% lower for SDG&E customers, though SDG&E is about 80% smaller than the other two and it already had by far the highest rates and solar penetration in 2019. (And that is based on the surprising 2024 decline in SDG&E rates, which is not expected to persist.)

(Source: For 2014-23, EIA-861 data with revenue adjusted for semi-annual Climate Credit. For 2023 and 2024, Utility Advice Letters.)

These calculations encompass a number of assumptions that are made clear in the spreadsheet. Possibly the most important is that households will consider only 2024 rates in making the adoption decision. Since rates are expected to rise faster than inflation for at least the next few years, this probably understates today’s incentive for a forward-looking customer.

Sure, the incentive to install isn’t as great for any of these customers as it was on April 14, 2023, when NEM 2.0 was about to end, but overall it isn’t that different from a few years ago when the industry was doing just fine, throwing itself parties, and growing at a healthy pace. The policy change has just stepped us back from the recent exponential growth in new systems, which is now creating exponential growth in cost shifts onto other ratepayers.

What’s “crushing” solar?

But if the incentive is still robust, why have new sales dropped off so much in the last year?

The first and most obvious reason iseverins that the much more generous compensation for systems installed before April 15 drove a goldrush during the first three and a half months of 2023. Many of those early-2023 buyers would most likely have been later-2023 buyers were it not for the rush to install before April 15 and lock in NEM 2.0 rules. In fact, overall 2023 sales of residential PV capacity were slightly higher than 2022.

But there remain a number of other drags on residential PV sales, factors that had been masked by the unprecedented growth in financial incentives from retail rate increases and NEM 2.0 policies.

It’s the interest rates

Rising interest rates makes any upfront capital investment that pays off gradually over decades less attractive. In fact, if a new solar system were financed at mortgage interest rates over 15 years, a buyer in 2023 would see a 21% higher monthly payment than a buyer in 2021 even though there was a slight decline in the cost of rooftop PV over the period.

(Source: Author calculations based on data from californiadgstats.ca.gov)

The big winners have already gone solar

Households considering solar differ in many ways, such as their roof size and orientation, their total electricity usage, their ability to finance a big capital investment, and their interest in environmental causes. The folks who jumped at rooftop PV over the last 10 years were the ones with the best sites, the highest electricity usage, access to low-cost financing, and the most interest in fighting climate change. A rooftop solar system lasts decades, so to maintain sales, companies have to convert new customers who were not that interested a couple of years ago. That makes it harder to keep up the growth year after year.

Slowdown in power shutoffs

In its 2019 “Year in Review” report, the Solar Energy Industries Association reported that “A crucial driver of growth for residential PV has been the public-safety power shutoff (PSPS) events in California. Beginning in H1 2019, these power shutoffs provided a key incentive for homeowners to purchase solar, increasingly paired with storage.” Back in fall 2019, so many people were asking how to deal with the PSPS disruptions that we had two different Energy Institute blog posts addressing the question.

Overall, from 2014 to 2019, the residential solar business in California grew at a 14% annual average rate. Then, after a flat 2020 during the pandemic disruption, sales exploded, more than doubling by 2022.

(Source)

PSPS events, however, have greatly diminished in the last couple years, in part due to better luck with the weather and in part because utilities have figured out how to shut off fewer houses when they have to deenergize a risky line. Fewer homes hit by PSPS events means fewer going solar (plus a battery) to minimize the disruption of blackouts.

(Source: Author calculations from the CPUC’s spreadsheet of PSPS events)

Time to stop policy wobbling

There’s now a move in the California legislature to reinstate the NEM 2.0 policy. This would override the CPUC NEM 3.0 decision, which was based on an extensive hearing process and careful reasoning to move compensation for rooftop solar in a more sustainable direction. With the drastically higher retail rates we now have, returning to full net metering would be a massive rooftop solar subsidy paid for by other – generally poorer – electricity customers. It would also drive rates much higher, making building and transportation electrification less affordable.

The rooftop solar market isn’t dying. It is coming down from the 2021-2023 sugar rush when net metering policies combined with rapidly-climbing electricity rates, recent power shutoffs, and the impending switch from NEM 2.0 to NEM 3.0 to produce growth that simply couldn’t be maintained. It’s tough to unwind bad policy when it creates outsize benefits for a small group of consumers and investors that are paid for by everyone else. But if we don’t do it now, it will be even tougher to address in the future. It is vital for California to chart a path that is sustainable and equitable, so it can be an example for other regions to follow, not a cautionary tale of what to avoid.

[NOTE: I updated this blog slightly on 4/18/2024 to reflect changes in the calculation of the incentive for installing solar based on changes in my calculations of average residential rates. The conclusion is not changed.]

I am posting frequently these days on Bluesky @severinborenstein

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, as well as subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation: Borenstein, Severin. “What’s Not Crushing California Rooftop Solar?” Energy Institute Blog, April 8, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/04/08/whats-not-crushing-california-rooftop-solar/

Categories

Severin Borenstein View All

Severin Borenstein is Professor of the Graduate School in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group at the Haas School of Business and Faculty Director of the Energy Institute at Haas. He received his A.B. from U.C. Berkeley and Ph.D. in Economics from M.I.T. His research focuses on the economics of renewable energy, economic policies for reducing greenhouse gases, and alternative models of retail electricity pricing. Borenstein is also a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, MA. He served on the Board of Governors of the California Power Exchange from 1997 to 2003. During 1999-2000, he was a member of the California Attorney General's Gasoline Price Task Force. In 2012-13, he served on the Emissions Market Assessment Committee, which advised the California Air Resources Board on the operation of California’s Cap and Trade market for greenhouse gases. In 2014, he was appointed to the California Energy Commission’s Petroleum Market Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 2015 until the Committee was dissolved in 2017. From 2015-2020, he served on the Advisory Council of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. Since 2019, he has been a member of the Governing Board of the California Independent System Operator.

Perhaps a future topic could look at why small residential battery storage installations are so expensive. Bringing down that cost would go a long way to improving the grid and lowering the payback period for residential solar.

We can all lobby our local jurisdictions to simplify the permitting and inspection process for adding battery storage. Some of the regulation is very antiquated. The new batteries are very safe. Permitting should be pretty much automatic when following a pre-approved plan, and inspecting should be very fast, or even delegated to certified installers.

Adding battery storage behind the meter for somebody who has a modern Solar installation should be pretty easy. Making it robust enough for blackout support is more expense, but just time-of-use shifting should be fairly easy, and that helps our utility bills and the grid.

APC Uninterruptable Power Supplies (UPS) have been providing safe back up power for homes and industry for over 40 years. Off the shelf, plug in, with low voltage batteries, these units have been approved for use worldwide. The come with built in batteries but can use external batteries for longer runs with Propper fusing. 12-volt and 24-volt configurations are very low cost and can run multiple devices from computers and printers to refrigerators, lights or televisions. Add a time clock for “time of day” switching to move devices off the grid and onto battery(s). UPS’s with “Cold Start” can even be used as backup generators. Replacement batteries are relatively inexpensive compared to todays overpriced lithium battery systems by using “glass Matt deep cycle lead acid” chemistry. There are other brands of UPS out there but many of the do not support “Cold Start”.

So many false statements, inaccurate computations and unrealistic assumptions that it is hard to believe this author can maintain any sort of credibility.

What a fascinating take from “anonymous”.

AB 2256 addresses that the CPUC did not account for “all” benefits of private sector investment in rooftop solar in creating a new NEM 3.0 tariff. As First District Court of Appeals Justice Alison Tucher pointed out in December 2023, it is unclear why any competent analysis would choose to disregard certain benefits in a tariff case. CPUC attorneys then argued that “the” benefits of solar doesn’t mean “all” benefits. To which Justice Tucher seemed especially interested to understand why the CPUC hadn’t included certain benefits in their cost benefit calculations. That is certainly worth examining.

Many feel the selected benefits promote cost-plus infrastructure contracts and handouts to Wall Street tax equity investors. Those assumptions are certainly baked into a lot of the analysis in pegging rooftop solar to solar farms while externalizing those factors. The excluded benefits then demote local economies, ecosystem conservation, prime farmlands, and infrastructure reduction. Based upon what is being accounted for, it appears that SB 100 has taken the environmental crisis and turned it into an infrastructure bill benefitting entrenched interests. The legislature is saying we should examine these concerns before dismissing them.

Many of the costs of solar farms have just been shifted to tax-payers (in the form of the rich not paying billions in taxes) and ratepayers (in cost-plus infrastructure that no one can afford). Solar farms are environmentally destructive. Liquidating the largest sources of capital humanity employs – natural resources and living systems- and calling them income without accounting for their permanent loss is poor economics.

The United States constitutes 5% of the world’s population consuming 24% of the world’s energy; it would take 5 planet earths for everyone to live like a U.S. resident; humanity is using nature 1.8 times faster than our planet’s biocapacity can regenerate. These ideas too are taught at UC Berkeley. By manipulating the numbers to promote an “all infrastructure” model, CPUC policy actually accelerates the damaging cycles that created our current crisis. There is a lot more going on here than just higher interest rates.

I’m scratching my head at numerous comments in this post, but perhaps the most regarding this assertion:

“Many of the costs of solar farms have just been shifted to tax-payers (in the form of the rich not paying billions in taxes) and ratepayers (in cost-plus infrastructure that no one can afford).”

Huh? How, exactly, do the rich avoid “paying billions in taxes” when solar farms are built? And how do they shift that cost “that no one can afford” on to the less well off?

California certainly does have an electricity affordability problem. NEM 3.0 at least makes a modest contribution to mitigating that probelm.

Rooftop solar panels generate electricity and the electricity, not used by the home, goes next door to the nearby homes and is used there and paid for there. Nothing really goes back to the utility except MONEY since many homes are connected to the load side of the step down transformer on the pole or underground in the neighborhood. The utility gives a credit to the homeowner producing the power at tier one rates while making a “profit” selling it to the next-door neighbor at tier two or even “time of day” rates making money even on NEM 1.0 or NEM 2.0. NEM 3.0 take 75% of the generated electricity away without any compensation then charges the full tier 2 or “time of day” rates to buy it back. If the utility had just taken 30% and not 75%, homeowners would still be able to make a payback profit on their rooftop solar investment. As it is, the Rooftop solar is no longer an investment and will no longer add value to their home under NEM3.0 and as the early adopters of rooftop solar get slammed into NEM3.0 at the end of their 20 years with the utilities with NEM1.0 or NEM2.0, they also will no longer get credit for the energy they generate onto the grid to carry them through the winter months. Soon, the higher fixed charges on residential meters will also make rooftop solar even less attractive since one can no longer get a payback check at the end of the years to compensate for the higher fees. Only by going completely off grid with a Rooftop Solar System could anyone ever generate enough to make a profit off of their system. Grid tied Residential Rooftop Solar is dead in California under NEM3.0.

See Argument#2 in https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/06/05/myths-that-solar-owners-tell-themselves/

Much of the blame for high rates resides with the excessive number of renewable contracts signed for extended periods from 2008 to 2015. PG&E knew by 2014 that it had too many contracts based on the rise of CCAs (I’ve seen the internal memos), and the 30 year terms on the PPAs foreclosed any opportunity for ratepayers to gain from the declining costs of solar and wind, except through installation of rooftop solar. In fact the cost of solar rooftop systems are comparable with the prices paid on average to those earlier renewable PPAs. (You can find the latter data in earlier CPUC reports.) As recently as 2021 those renewable PPAs represented half of the excess of generation costs over market benchmarks used to calculate the PCIA (which have been higher than the values from the Avoided Cost Calculator). For PG&E and SCE that amounted to a billion dollars annually each. Along with the billion a year added by the PG&E settlement debacle (which I criticized in 1996), they are approached the purported “cost shift” from NEM customers. Where’s the outrage over those management mistakes?

PG&E had an opportunity to lay off a large portion of those contracts on the early CCAs but instead tried to kill those agencies to protect its monopoly. If PG&E had instead sold it interests in a set of those PPAs, our rates would be much lower.

Thanks for continuing to educate us on these topics. I looked at my PCIA and I see our cost is fairly low, so I assume the value depends on multiple parameters. We joined our CCA a while back, so perhaps vintage is one of the variables? I’ll try to learn more.

The general public needs more education on all of this. Even a customer with interest on the topic will have trouble understanding how it all fits together, and the rules keep changing.

Peak times keep changing too as does the amount of curtailment on the CASIO grid at this time of year. I learned a lot about costs and how they are allocated after reading a PG&E general rate case long ago.

Mark Miller

Rich:

Yes, PG&E’s 2010 ballot effort to derail the formation of CCAs was ill-conceived and reflected a lack of foresight. PG&E should have known — and probabaly did know — that once the DWR exit fee charges began to taper off after 2010, CCAs would become not only viable but attractive. (None of the IOUs opposed Migden’s AB 117 which established the CCAs in 2002. I negotiated that bill for Gov. Davis with Migden’s office, and the IOU reps told me as long as the bill contained provisions to prevent cost-shifting they were ok with it.)

That said, you maintain that “Much of the blame for high rates resides with the excessive number of renewable contracts signed for extended periods from 2008 to 2015.” The Great Recession defined 2008, of course, and the prospects for clean energy then were grim. As John White told The New York Times, “Everyone is in shock about what the new world is going to be. Surely, renewable energy projects and new technologies are at risk,” he glumly observed, “because of their capital intensity.”

Fortunately, Obama managed to get $90 billion for clean energy projects in the 2009 Stimulus Bill — a Godsend, as White told me last year. And, as clean energy innovator Varun Sivaram stated in 2020, after PG&E and SCE — purusant to the state’s RPS and with help from the intital Stimulus loan guarantees — signed PPAs for power from five utility-scale solar projects, “the floodgates opened for private financing of utility-scale projects in the U.S.” Combined with increased R&D, this stands as a huge step forward for sustainable energy.

Were too many long-term contracts signed by PG&E (and perhaps Edison)? Maybe so. I’ll live with that. But I find it hard to believe that, as you assert, “As recently as 2021 those renewable PPAs represented half of the excess of generation costs over market benchmarks used to calculate the PCIA.” Let me state up front that I’m not sure what you mean by “excess generation costs,” but haven’t Severin and Jim Bushnell shown that a large amount of high IOU rates can be attributed to “public interest” programs that are layered on top of the energy charges in those rates?

Just as in 2001 when DWR overprocured long term contracts aiming for “100%” of future loads, all 3 IOUs also overprocured from 2008 to 2015, even long after it was readily apparent that (1) loads had flattened substantially so the need was much smaller than thought in 2008 (2) CCAs were rising (and I’ve seen the memo that PG&E was well aware of this issue) and (3) solar panel costs were dropping precipitously so waiting to procure more would be economically beneficial. The state’s utilities seemed to learn nothing from the earlier episode. The passage of AB 57 in 2002 that protected IOUs from any subsequent review of their generation-related management decisions combined with the only incentive presented as a $50/MWH penalty for underprocuring renewables unleashed the IOUs procurement. (There are no penalties or other incentives for good portfolio management in the confidential Bundled Procurement Plans which I’ve read.)

As for the share of excess stranded generation costs recovered through the PCIA (which by the way uses a market price benchmark which is higher than what the Avoided Cost Calculator produces), it was approximately half of the total generation cost (for PG&E $2.5 billion out of $5 billion in revenue requirements) and from my review of the confidential work papers as an expert witness, the RPS PPAs were about half of that excess. High recent gas prices has narrowed the stranded asset cost and the end of the conventional cost recovery for Diablo Canyon will largely eliminate that portion of the PCIA. So as of 2025 almost 100% of the PCIA stranded asset charge will be for RPS PPAs.

Rich: Again, you maintain that “Much of the blame for high rates resides with the excessive number of renewable contracts signed for extended periods from 2008 to 2015.”

The PCIA matter aside, what is the basis of your assertion regarding current IOU rates? For context (and counterpoint), I would point to this excerpt from the analysis of AB 1912 (Pacheco) by the Assembly Committee on Utilities and Energy on last month:

“Primary Drivers for High Electric Rates: The independent Public Advocates Office has reported

that the primary drivers for utility cost increases in recent years are due to wildfire mitigation,

distribution and transmission infrastructure investments [including ‘hardening’], and rooftop solar incentives provided to some customers through net energy metering.7 Additionally, a recent report by the State Auditor

concurs with those findings.8″

As part of our 2021 study of high California electricity rates, we looked into the argument that renewables contracts were increasing electricity prices more than other energy contracts. It may have been true in the early 2010s, but it was not true by 2019. The average cost of renewable and nonrenewable energy were less than $0.01/kWh apart. In both cases, more expensive contracts from years earlier raise the average price above the 2019 market price.

See section 5.1 of this report https://haas.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/WP314.pdf

The message of NEM 3.0 / NBT has been: ‘you need to add battery’. This is regardless of whatever today’s rates do. From the perspective of the property owner, this is extra cash to spend. From the perspective of the installer, battery installers are very different companies than solar installers, and from so are from the perspective of the permitting.

Personally, I am OK with the changes but the transition from NEM 2.0 to NBT was rushed. And it also caused lack of faith in the system – that, plus all the noise about Income-Based Fixed Rates. All these changes make people unsure about the set of rules they will have to abide to.

Separate is the whole VNEM and NEMA decision. Hopefully that will be addressed.

I took into account Time of Use metering. Using your assumptions, the amount of energy consumed during the peak would be 5400kWh. Half of the energy generated would be consumed, so I assumed that not during peak.

The peak energy consumed would be sold to the consumer at “Non-CARE avg rate” ($0.432). The non-peak energy would be sold at $0.30/kWh. The exported energy would be purchased by the utility at the avoided cost (7.5¢/kWh).

These numbers yield a savings of $868. I admit my assumption is not great, so I assumed the opposite, all the exported energy is consumed at peak … savings $1421.

So why are my savings numbers so different from yours? I didn’t factor in CARE because previously you asserted that CARE recipients are too poor to be able afford solar.

I’d also like to note that “avoided costs” does not reflect the reality that rooftop solar generates retail energy.

Solar electrical power from installed Rooftop Solar systems, without batteries, over the 25-year lifetime, costs 10 Cents per kilowatt hour to produce on average IN 2024. A utility paying 7.5 cents for that power is a non-starter for new systems under NEM3.0. Investing in rooftop solar systems with batteries is a losing proposition and the money is best spent elsewhere or invested in mutual funds or variable annuities. With Solar Companies going out of business and the warranties in limbo, the investment will become a liability at the time of sale. Going “off grid” in California is the only way forward for rooftop solar under NEM3.0 using lead acid deep cycle batteries since lithium batteries have become too expensive and disconnecting from the grid from 4:00 PM until 9:00 PM daily.

“This would override the CPUC NEM 3.0 decision, which was based on an extensive hearing process and careful reasoning to move compensation for rooftop solar in a more sustainable direction. “

Having been a participant in those proceedings and seeing the significant errors made in reasoning, especially regarding VNEM and NEMA, I disagree strongly with this statement.

It starts with the fact that the Avoided Cost Calculator was updated without full participation of those who involved in the NEM 3 proceedings because the CPUC failed to notify stakeholders of its potential importance. The ACC had been a backwater used only in the energy efficiency proceedings where its findings were ignored or adjusted to come to an acceptable answer. It lacks rigor and a methodology that correctly captures the full value of alternatives resources because its caught up in conventionality of a bygone era.

And the ALJs in the NEM case clearly didn’t understand the physics of the distribution system nor the relationship of tenants and landlords or how contiguous parcels relate to the grid.

The whole proceeding reflected how the CPUC has become so captured by the utilities.

The VNEM and NEMA ruling was atrocious for all parties, including renters – well the IOUs benefited. Hopefully SB1374 (Becker) will fix this.

“Since rates are expected to rise faster than inflation for at least the next few years, this probably understates today’s incentive for a forward-looking customer.”

Why is it always taken as a given that prices must increase faster than inflation and that the IOUs must continue to charge the highest (or second highest) rates in the nation in California?

I realize it’s not as interesting, policy-wise, as some of these other questions, but unless California can fix the continuous rapid electricy-rate price increases, the 2035 EV mandate stands zero chance of surviving. And no, soaking higher income households with a $1000/year electricity surcharge to subsidize other households, as PG&E and others proposed last year, is not going to do the trick.

Have you folks looked at commercial/industrial rooftop solar? I am wondering about the attractiveness of thinking of large, vacant rooftops as “virtual land” where a developer comes in, pays the building owner a rental fee, and then sells the electricity to the utility (possibly after netting generation by selling some of the electricity to the building owner, if they would pay more per cent than the utility). My point is, that the PV does not need to be limited by the amount of electricity used in the building below…. wouldn’t that be better than developing PV (and transmission) out in the desert and then transmitting that to load centers?

Maybe we could discuss further?

thar us basically what Community Solar programs try to address and a great future topic.

Excellent write-up and analysis, Severin……sometimes the truth backed by facts hurts the ambitions of certain segments of the clean energy business. It is also worth noting that the big players in the California Roof-Top Solar Installation Market speak less of “bad NEM 3.0 policy” and more about “their primary competition being IOU electric rates”. The “way above inflation” rise in IOU electricity rates—–driven primarily by wildfire mitigation costs (questionable in both efficacy and cost, in my view) continues to make California an attractive market for solar rooftop. This is not to say that CPUC policies around distributed generation are perfect. Far from it, as evidenced by the state’s lagging policies around community solar and microgrids. NEM 3.0 HAS helped improve solar + storage attachment rates, which is a good thing.

Thank you for shining the light on a highly charged subject.

Solar plus storage more than doubles the cost because the solar will last at least 25 years but the storage (batteries) only lasts 12 to 14 years before needing a Compleat replacement. Doing the math, adding lithium batteries does not cover their cost before they burn out or go dead. Just a note, running a whole house inverter generator between 4:00 PM and 9:00 PM is cheaper than buying Utility Peak time power on any fuel now in California. Where a solar plus battery system runs $56,000.00 or more, the whole house inverter generator costs less than $5,000.00 and will outlast the Tesla Power walls if maintained and used daily. We are going backwards in California.

A big flaw in the narrative that NBT helps with solar + storage is that the installers for solar are usually not able to install batteries, and that permits and inspection regulations have not yet changed to accomodate the NBT assumptions.

The change to NBT should have given much more time to transition from one model to the other. Anybody in the business should have understood this. It baffles me that the CPUC acted how it did; it was irresponsible.

….”It’s tough to unwind bad policy when it creates outsize benefits for a small group of consumers and investors that are paid for by everyone else. But if we don’t do it now,,….”

That about says it all.

“Free market” versus “Managed Grid (CPUC governors)”; Given the “politics” of such remarks is —

“..we’ll manage if for,..(‘California Values’)” versus “independent”/Justice is blind” approach.

CPUC is a bunch of unelected officials (granted extra-judicial powers) by the governor.

And when legislature tries to act (SB 420, Becker) and votes overwhelmingly for it (40-0 and 78-1-1), Gov Newsom vetoes it… and our legislature has not seen fit to override a veto in decades

Yes, Severin—I agree with a lot of these commentors, that your article is bullshi when it comesto blaming NEM 2.0 for a “Cost-shift”. You sound like you were paid off by the utility companies. In fighting climate change, the most important goal isto encourage more green energy production and distrubutedsolar energy should be incentivized as much as possible . Maybe the utility companies felt they were losing some revenue. Yes, so what! Take the money from their excessive executive pay or stockholder benefits. Or at least be more effiicient in what you pay for–expecially do not do undergrounding of lines when youshould be strenghtening the lines in fire territory. Oh , but wait, PGE doesn’t make as much money off of that . They want to get their 10% guaranteed profits off the more expensive undergrounding costs.

Just to address the frequent response that I am paid off by the utilities in some way:

– I receive no income from the utilities through consulting or the University

– The Energy Institute receives donations from a wide variety of entities including California investor-owned utilities. No energy company contributes more than 2% of the EI budget. The vast majority of our funding comes from grants from government agencies and foundations.

– I have written numerous blog posts that utilities are not happy about. This one for instance: https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2022/10/03/what-does-capital-really-cost-a-utility/ , which describes research by two of our former graduate students that suggests utility allowed rates of return are way too high.

– My views on the problem with the way we are incentivizing rooftop solar are shared by the CPUC’s Public Advocate Office (which is independent from the regulatory side of the commission), the ratepayer advocate group The Utility Reform Network (TURN, which disagrees with utilities on most things), and the Natural Resources of Defense Council, among other organizations.