Raising the Price of Emissions in California

California is tightening its GHG belt – who should feel the pinch?

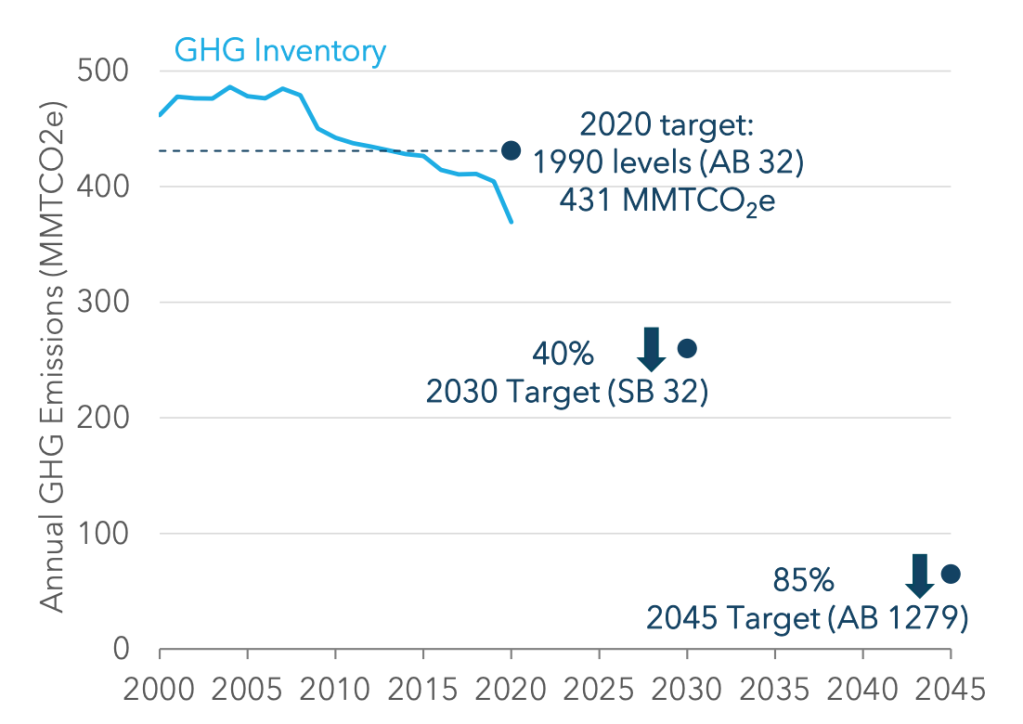

California has set some ambitious GHG reduction goals. Now the state is trying to figure out how to meet them. The costs of unmitigated climate change could be devastating, so we should be looking for ways to drive deeper reductions in GHG emissions. Mitigating climate change won’t be cheap, so we should be chasing down the most cost-effective strategies.

California’s GHG cap-and-trade program was designed to incentivize cost-effective emissions reductions with the help of a carbon price. But the current program was not set up to meet these increasingly ambitious climate goals, so the carbon price signal is relatively weak. While carbon prices are currently ~ $40/ton, cost estimates for some prescriptive measures included in the scoping plan exceed $200/ton.

If we are serious about containing the costs of climate change mitigation, we should be serious about squeezing more low-cost GHG reductions out of the carbon market. A post-2030 reauthorization, including proposals to tighten the cap and reduce the supply of GHG allowances, is now under discussion. How will a tighter budget of GHG allowances be allocated across competing interests? This week’s blog post weighs some of the options.

Abatement supply and demand

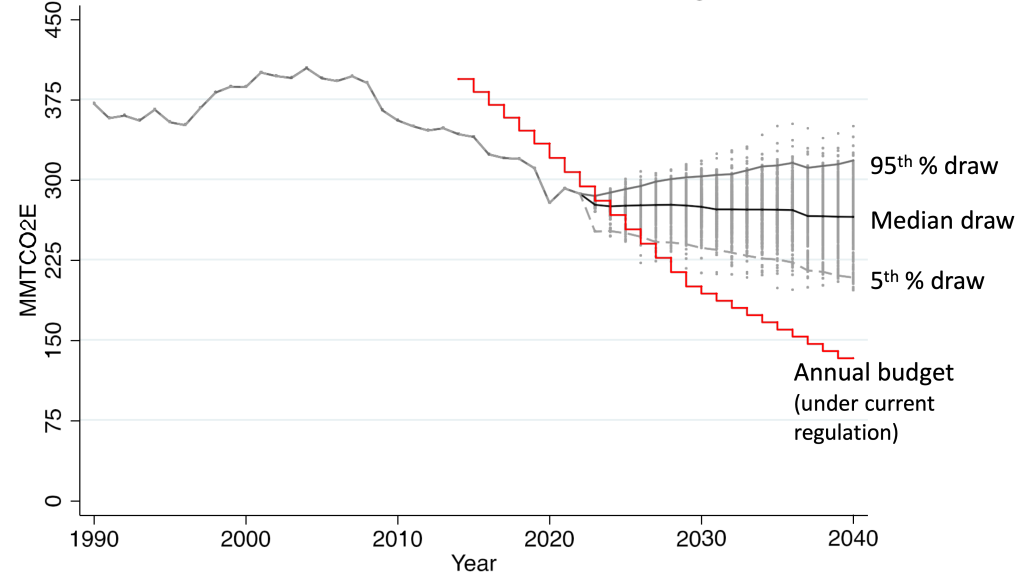

An A-team of UC Davis economists has been modeling how supply and demand for GHG emissions reductions could evolve through 2030 and beyond. This analysis projects GHG emissions under a modeled “business as usual” and compares the implied demand for allowances against alternative GHG allowance budgets or caps.

Jim unpacked some of this analysis in his recent blog post. Preliminary results project a surplus of GHG allowances under a scenario in which the program is not extended past 2030. Under this (unlikely I hope) scenario, the allowance market would clear at the floor price, providing a weak incentive for GHG abatement. Projections look quite different if the cap-and-trade program is re-authorized and allowances are allocated according to the post-2030 allowance abatement formula in the existing regulation. A reauthorization would immediately increase allowance prices, providing stronger abatement incentives through 2030 and beyond.

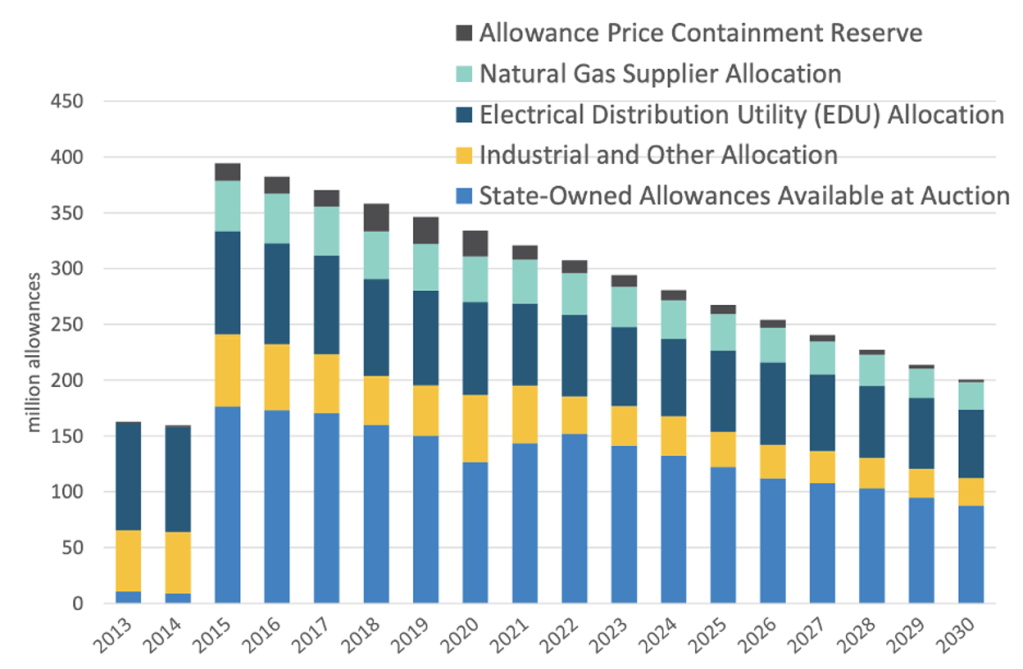

Reauthorizing the program along the lines of existing regulations would be an important step in the right direction, but it would not deliver GHG reductions commensurate with California’s current GHG targets. With this in mind, policymakers are contemplating a further tightening of allowance supply. These discussions have primarily focused on three sources: state-owned allowances; free allocations to industry; and free allocations to electricity/gas utilities. The graphic below shows how allowances are currently allocated to these sources:

Each of the allocation streams in this figure generates benefits for stakeholders.

- Allowances that enter the market through a revenue-raising auction generate proceeds for the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) to support affordable housing, public transit projects, and other public investments.

- Allocations to industrial producers are designed to mitigate emissions leakage and competitiveness impacts in trade-exposed sectors.

- Allocations to electricity and natural gas utilities are used to mitigate increases in households’ utility bills.

These are all valuable objectives or uses. So, when the GHG budget tightens, who should get fewer allowances?

When the GHG budget is tightened, who should feel the pinch?

Budget tightening is hard. No one wants to see their share of the pie get smaller. In this context, it is important to remember that as the number of allowances is reduced, the value of an allowance rises. So a reduction in compliance value (measured in tons of GHGs) need not imply a reduction in monetary value (measured in $$$). Nevertheless, the allocation of future allowances feels like a zero-sum game.

Negotiations will, inevitably, be political. It will be important to weigh all possible options. Along these lines, there is another source of future allowance supply that is not shown in the allowance allocation graphic above. It’s estimated that there are at over 337 million allowances “in the bank”. As the allowance price rises, owners of these banked permits will sell them back into the market

Under current market rules, allowances in the bank today are worth one ton of GHG emissions in the future, regardless of when they are used for compliance purposes. It was recently pointed out (not by CARB) that a reduction in the future compliance value of banked permits could offer another way to reduce future allowance supply. In other words, banking rules could be changed so that a permit in the bank today is worth less than a GHG ton after some future date.

In principle, reducing the compliance value of permits in the bank today would shift some of the budget-tightening pressure off of other stakeholders (e.g. utility customers, GGRF fund beneficiaries) and onto owners of banked allowances. Owners of banked allowances include not only compliance entities (i.e. some of the same entities who receive free allocations), but also non-compliance entities who are holding banked permits as an investment.

I see the value in considering all the options when negotiating reductions in GHG allowance allocations. However, I have two concerns about using banking rule modifications to reign in future allowance supply.

The first has to do with market confidence and market efficiency. Allowance banking serves an important purpose in providing compliance flexibility and reducing compliance costs. Protecting the integrity of the bank is important for ongoing confidence in the California market. Sudden or unanticipated rule changes would undermine confidence in the market and limit future compliance flexibility.

A second concern has to do with unintended carbon price consequences. If the objective is to increase the GHG price to incentivize more emissions reductions, reducing the compliance value of banked permits could have the opposite effect in the near term. A reduction in allowance supply that is achieved by reducing the aggregate number of allowances allocated would immediately increase the GHG allowance price, providing a strong and sustained incentive for cost-effective GHG abatement. In contrast, if part of the reduction in market supply is achieved by reducing the compliance value of banked permits at some future date, this would induce holders of banked permits to sell more allowances into the market before they get devalued.

An accelerated liquidation of banked allowances would drive allowance prices down in the near term (how far down would depend on how much compliance value is discounted and where the floor price has been set). Following the devaluation date, the allowance price would rise. Over the life of the program, reducing allowance supply via a devaluation of banked allowances could deliver fewer GHG reductions as compared to other means.

Raising the price of emissions in California

At this point, the most important step California can take to encourage more cost-effective abatement through the cap and trade program is to re-authorize the program beyond 2030 and resolve the regulatory uncertainty around what that program will look like. This will provide an opportunity to align the cap with the state’s GHG reduction goals and re-visit how allowances are allocated across competing interests.

Dividing a valuable GHG allowance allocation pie among competing interests will be challenging and fraught. Fairness concerns must be weighed against other critical objectives, including market stability, compliance flexibility, affordability, and improving conditions in disadvantaged communities. CARB has a busy summer ahead and we all have a stake in seeing this process succeed.

Worth noting: The views expressed in this blog are my own and should not be attributed to my excellent Independent Emissions Market Advisory Committee colleagues.

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, as well as subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation: Fowlie, Meredith. “Raising the Price of Emissions in California” Energy Institute Blog, April 1, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/04/01/raising-the-price-of-emissions-in-california/

Categories

As Meredith notes, “California’s GHG cap-and-trade program was designed to incentivize cost-effective emissions reductions with the help of a carbon price.” I would add that the CATP was also supposed to serve as a model for other states and, indeed, the federal government and other countries. The near-term aftermath of AB 32 led to the halcyon days of the Western Climate Initiative and the passage of the American Clean Energy and Secturity Act of 2009 in the House. But in 2010, it all came crashing down. (As Bill McKibben noted in his 2021 oral history interview on the Obama years, the effort at that time “wasn’t politically possible. The lift was much, much too heavy.”)

However, 14 years later, California’s CATP is chugging along, now in tandem with Quebec. This fact is attests to the dogged perseverance of many stakeholders and, yes, to some notable degree of effective policymaking, the headwinds (and leakage risk) of essentially going it alone notwithstanding. That perseverance writ large certainly helped Biden’s IRA get enacted, along with Obama’s critical green stimulus funding in 2009.

It is important to squeeze “more low-cost GHG reductions out of the carbon market” in California as Meredith asserts. But let’s also try to do that in a way that can readily facilitate GHG emission reductions elsewhere in the world. As Severin noted in a 2014 blog post, “If we don’t solve the problem in the developing world, we don’t solve the problem.” That credo would be a good bumper sticker (albeit a big one for sufficient letter size).

Yes, the process for California to determine its GHG emissions policy and related actions in the years ahead will be “challenging and fraught.” And I’m glad we have a lot of bright minds here to take that on, as evinced by Meredith’s post. But to the extent that we, here in California — the fifth largest economy in the world — are having palpitations over cost concerns, how realistic is it to expect developing nations to follow in our climate policy footsteps?

I still strongly agree with the assertion Severin made in that blog post 10 years ago: “We need to refocus on how California can realistically contribute to solving the problem of global climate change. …If we can do that, we can avert the fundamental risk of climate change. If we don’t do that, reducing California’s carbon footprint won’t matter.”

The recommendation to kick the can down the road by extending cap and trade beyond 2030 and then figuring out the reforms discussed here is telling. It says we don’t know what to do and more time won’t change that. Tweaking and adding more “features” (there are now 23 among California, RGGI and the EU ETS) will likely lead to more “unanticipated” consequences.

It has been a decade and the paucity of credible independent evaluations to determine the causality, or lack thereof, between climate programs and emissions doesn’t speak well (with all due respect to the IEMAC).

Cap and trade experience has been flawed from the beginning due to its inherent characteristics:

As a result, cap and trade devolves into an increasingly complex government administratively controlled program. Information asymmetry means there is a low probability of “getting it right.”

What to do? Hit the glide path and land it in 2030. Initiate a low escalating simple carbon fee (like Canada) in 2028 with half the revenues returned to households to facilitate their transition to electricity. Devote the other half to the cost-effective complementary subsidy/regulatory programs and to research, development and demonstration.

California’s comparative advantage is clean technology research and financing innovation—not climate policy. The danger is greatest in emerging economies where emissions growth is fastest. California’s cap and trade is a poor fit for emerging economies with weak institutions and serious corruption. And the IRA and California subsidy approaches are a misfit as well—no fiscal space (IMF).

Robert Archer

Meredith, regarding cap-and-trade reauthorization, can you respond to this question, which neither the IEMAC nor CARB addressed at the March 11 JLCCCP Annual Oversight Hearing?:

Has the cap-and-trade program achieved the “maximum technologically feasible and cost-effective greenhouse gas emission reductions” required by AB 32?

I lost my home in a fire and last September, I decided to go all electric in my re-built home. After the PG&E Electricity price gouging increase for Electricity in January 2024, I opted back to Natural Gas because it is cheaper, and the ELECTRIC Mandates are being eliminated. Until Electricity is a more cost-effective option than Natural Gas, consumers will fight back. Berkley California and other cities have withdrawn the electric ONLY mandates BECAUSE consumers are also voters, and they are angry about the higher ELETRICITY prices and are resentful about costly mandates. When Natural Gas costs more than Cleanly produced Electricity, then the change will come. Money talks.

Berkeley withdrew its ban on new gas connections because of a lawsuit by the restaurant association funded by gas utilities. It had nothing to do with voters.

And you’re in for a surprise over the next decade as utility gas prices skyrocket due to declining use (which was already happening before line extension allowances were ended and more effective Reach Codes that close off the gas option were enacted in other cities.)

Good points. This is why I am pre-wired and plumbed for heat exchanger hot water, heat exchanger mini-splits for the house and master bedroom and for the inevitable EV in the garage 50-amp level two charging. But buying the actual appliance or EV will be done when the Government Rebates are large enough to pay for them or I need them because natural Gas prices eventually reach high enough costs to warrant the purchase of the upgrades. I still plan on getting the induction Range as planned since it is cleaner and less costly to operate than electric resistance heating coils.

VALUABLE OBJECTIVE: ”…to support affordable housing…other public investments”? What does that have to do with the purpose of reducing GHG emissions? Carbon credits are supposed to be revenue neutral so that it doesn’t adversely impact the economy while motivating that the most cost effective ways of achieving reductions is achieved. This feels like theft. Revenues generated by carbon pricing should either go into further advancement of technologies that reduce GHG emissions, systems like transit that reduce GHG emmissions, lower fares of public transit that reduce GHG emissions, infrastructure projects that would mitigate the impacts of climate change and otherwise come out of general fund, or should be used to lower tax rate. If the Politicos can’t keep their grubby hands off of the revenues generated from carbon pricing, then it is only a new form of taxation, and nobody will support it. We can’t achieve the goals of GHG reductions if all the increased carbon pricing does is make everyone poorer and poorer.

VALUABLE OBJECTIVE: ”…to support affordable housing…other public investments”? What does that have to do with the purpose of reducing GHG emissions? Carbon credits are supposed to be revenue neutral so that it doesn’t adversely impact the economy while motivating that the most cost effective ways of achieving reductions is achieved. This feels like theft. Revenues generated by carbon pricing should either go into further advancement of technologies that reduce GHG emissions (and would have otherwise been funded by the state), systems like transit that reduce GHG emmissions, lower fares of public transit that reduce GHG emissions, infrastructure projects that would mitigate the impacts of climate change (and otherwise come out of general fund), or should be used to lower tax rate. If the Politicos can’t keep their grubby hands off of the revenues generated from carbon pricing, then it is only a new form of taxation, and nobody will support it. We can’t achieve the goals of GHG reductions if all the increased carbon pricing does is make everyone poorer and poorer. There’s not an infinite pot of gold available to do the pet projects of Politicos not in any way attached to GHG emissions. It has to be managed to be net neutral to the taxpayers or it doesn’t work.

Finally, someone (besides me) dared to write it, “mitigating climate change won’t be cheap”. But it absolutely does not follow “so we should be chasing down the most cost-effective strategies” If we don’t mitigate climate change we’re dead, but not just “dead, dead”, extinct dead.

Cancer patients will spend millions of dollars to get a few more months of life. I was glad to do it for my wife. We weren’t looking for “cost-effective”, we were looking for “effective”, period. And that’s for what we should be looking now in climate change, effective.

The other thing no one is saying, “Climate change is going to be inconvenient.” We’re going to have to change our lifestyles. Better said though, without a doubt, our lifestyles are going to change, We can chose to change them now, or later, Mother Nature will change them for us.