Petroleum Diesel is Disappearing from California

The state’s low carbon fuel standard is driving a shift to renewable diesel.

This week we add a new voice to the EI blog, Aaron Smith, who is the newest Energy Institute Faculty Affiliate. Aaron is currently a professor at UC Davis who works on agricultural economics and biofuels. He blogs regularly at https://agdatanews.substack.com/ on topics related to agriculture, economics, and data. In July 2024, he will be moving to UC Berkeley’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

California trucks and trains burn about 3.5 billion gallons of diesel per year. Five years ago, petroleum supplied 85% of diesel. In the first quarter of 2023, less than half the state’s diesel came from petroleum. Most California diesel is now made from animal fat, corn oil, soybean oil, or used cooking oil.

This trend is likely to continue. Under current policy, there is a high chance there will be no petroleum diesel used in the state by 2030. That’s one conclusion of a recently released working paper by Jim Bushnell, Gabriel Lade, Julie Witcover, Wuzheqian Xiao, and me.

What are the Alternatives to Petroleum Diesel?

Rudolf Diesel experimented with multiple fuel sources when developing his engine in the late 1800s, including kerosene, coal dust, and vegetable oils. At the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, he displayed a prototype that ran on peanut oil. Modern diesel engines require a fuel that is less viscous than vegetable oil, so pouring peanut oil into your diesel engine is a bad idea. However, two products of vegetable oils and fats work well in modern diesel engines: biodiesel and renewable diesel.

Biodiesel is produced through a chemical process that reacts organic oils and fats with alcohols and catalysts. Biodiesel has some limitations that curb its use, including a lower energy density than petroleum diesel, potential corrosion of storage tanks, potential clogging of fuel lines, and sensitivity to the cold.

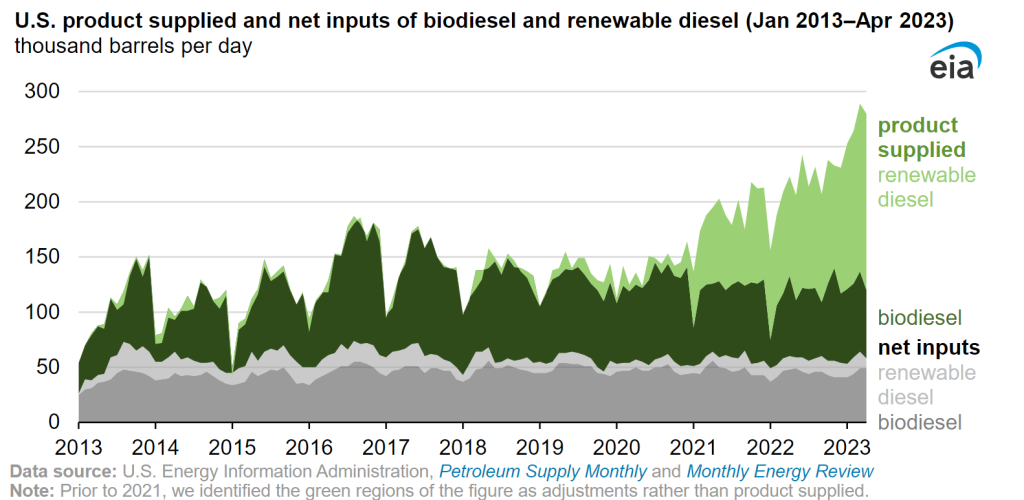

Renewable diesel doesn’t have the drawbacks of biodiesel, but it is more expensive to produce. It is created by reacting hydrogen and catalysts with oils or fats under high temperature and pressure. This process removes oxygen, leaving a fuel that contains only hydrogen and carbon; it is a hydrocarbon just like petroleum diesel and can be used in diesel engines without restriction. Renewable diesel production capacity in the United States has boomed in the past couple of years as oil refineries have repurposed to produce the fuel. Almost all United States renewable diesel is consumed in California.

Why have Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Increased So Much in CA?

California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) is a state policy that currently requires a 20% reduction in the carbon intensity (CI) of transportation fuels below 2010 levels by 2030. Similar to CAFE and RPS, the LCFS requires the average CI across all transportation fuels to be at or below a specified target. This policy is the primary driver of the increase in biodiesel and renewable diesel in the state.

Here’s how the LCFS works. The California Air Resources Board determines the CI of all the fuels in the state using a life cycle analysis that accounts for tailpipe emissions as well as potential emissions throughout the fuel production process. There are currently 815 active fuels with an approved CI.

For example, renewable diesel produced by co-processing soybean oil with fossil feedstock in a diesel hydrotreater at Chevron’s El Segundo refinery using soybean oil transported by rail to California has CI of 51.74 grams of CO2 equivalent per megajoule of energy. That’s a mouthful, and it illustrates the myriad ways that even renewable fuels can emit carbon. Petroleum diesel has a CI of 100.45, almost twice as large.

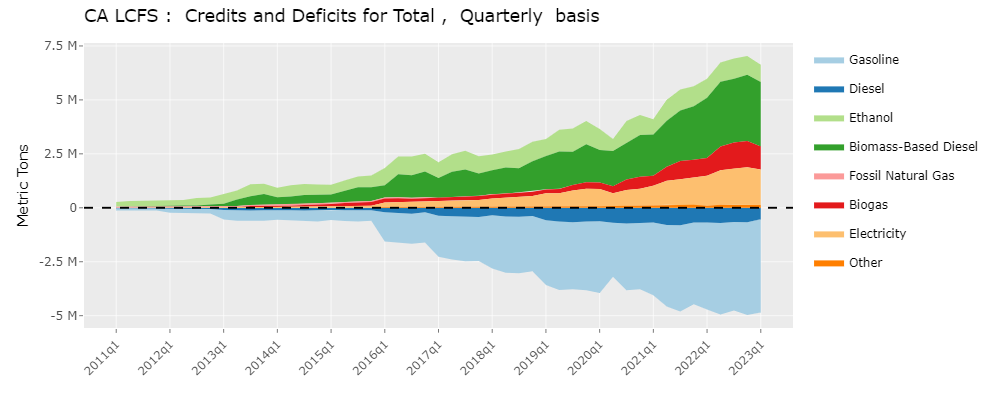

In 2023, the CI target for diesel is 88.15, which is 11% below 2010 levels. A fuel supplier could hit the target with a blend of 75% petroleum and 25% renewable diesel. In aggregate across all transportation fuels, the total deficits (number of CI units above the target) need to be offset by the total credits (number of CI units below the target). Fuel suppliers with a net deficit can reach compliance by buying credits from suppliers with a net credit.

In the first quarter of 2023, petroleum diesel generated 532,000 metric tons of CO2 deficits in California. Biomass-based diesel (BBD), which encompasses biodiesel and renewable diesel, generated 2.99 million metric tons of credits, which more than offsets the deficits from petroleum diesel and is substantially more than other prominent credit-generating fuels such as ethanol, electricity, and biogas.

In 2019 and 2020, credits were scarce, which pushed credit prices to their ceiling of just over $200 per ton. The boom in renewable diesel has relieved pressure on the LCFS, and as a result credit prices have dropped. In response, the Air Resources Board is considering tightening the targets from the current 20% to between 25% and 35% CI reduction below 2010 levels by 2030.

Will the Renewable Diesel Trend Continue?

To answer this question, my co-authors and I built a statistical model (a cointegrated vector autoregression) to forecast fuel demand through 2035. The model uses six quarterly variables: California vehicle miles traveled, California gross state product, Brent oil price, soybean price, California diesel consumption, and California gasoline consumption.

The model accounts for uncertainty. We don’t know what will happen in the state economy in the next 12 years, so it is better to predict the range of possible outcomes and their associated probabilities rather than calculating a single prediction. Our median forecast is for consumption of diesel-equivalent fuels to continue growing as the state economy grows and for consumption of gasoline equivalent fuels to remain flat as fuel economy continues improving. There are a wide range of possibilities around the median.

VAR forecasts of diesel and gasoline equivalent consumption. Source: Bushnell et al, 2023.

Next, we take these forecasts and ask what it would take to achieve LCFS compliance.

This exercise requires numerous assumptions about the number of credits from various sources. We treat all credit generating fuels as price insensitive except BBD. Our main assumptions are that (i) ethanol will remain 10% of the gasoline pool, (ii) the number of light-duty electric vehicles (EVs) will increase steadily to 5 million in 2030 and 10.5 million in 2035, (iii) each light-duty EV displaces 80% of the miles that would have been driven by an internal combustion engine vehicle, (iv) the number of credits from biogas will approximately double by 2030 and remain constant subsequently, and (v) the fleet composition of medium and heavy-duty vehicles will follow projections in the 2022 Scoping Plan Scenario. See the paper for additional assumptions covering forklifts, alternative jet fuel, and other components.

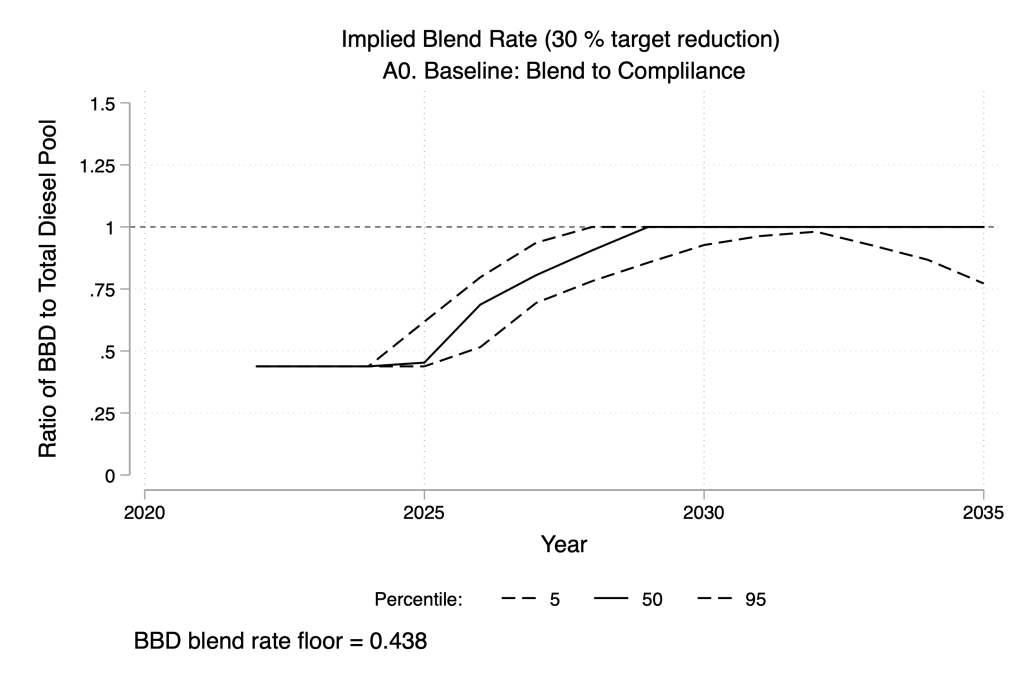

With these assumptions in place, we next calculate how much BBD would be needed to reach compliance with a new LCFS target of 30% CI reduction below 2010 levels by 2030. We assume that the percentage of BBD in the diesel pool does not drop below 2022 levels and that additional BBD will have to come from high-CI feedstocks such as soybean oil because low-CI feedstocks such as used cooking oils and animal fats are “nearly tapped out”.

By 2028, we project at least a 50% probability that the California diesel pool will have no petroleum. By 2032, there is almost a 95% probability of no petroleum diesel. The pressure to eliminate petroleum diesel may be relieved somewhat after 2032 if electric and hydrogen medium and heavy duty vehicles enter the fleet in the numbers predicted in the scoping plan. Electricity and hydrogen will likely have a lower CI than BBD, so introducing them would allow some BBD to revert to petroleum without exceeding the LCFS.

Altering our assumptions about the trajectory of other credit-generating fuels changes the probability that petroleum diesel disappears from the state, but all scenarios we consider produce a high probability that the vast majority of diesel is biomass based. This will create pressure on US agricultural markets as almost half of soybean oil is already used to produce BBD.

If the BBD blend rate hits 100%, further LCFS compliance must come from less price sensitive sources. The LCFS credit price is likely to return to the ceiling to reflect the scarcity of available credits from these sources. With petroleum diesel disappearing, gasoline will essentially be the only deficit generator, which means that gasoline suppliers will need to acquire expensive credits to achieve LCFS compliance—the cost of which will be passed along to consumers.

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas

Suggested citation: Smith, Aaron. “Petroleum Diesel is Disappearing from California” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, October 2, 2023, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2023/10/02/petroleum-diesel-is-disappearing-from-california/

Categories

Aaron Smith View All

Aaron Smith is the DeLoach Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California, Davis, where he has been since 2001. Originally from New Zealand, he earned his PhD in Economics from the University of California, San Diego. His research addresses economic and policy challenges related to agriculture, energy, and the environment. He has over 50 publications in refereed journals, including outlets such as the Review of Economics and Statistics, the Journal of Econometrics, the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. His research has won the Quality of Communication, Quality of Research Discovery, and Outstanding American Journal of Agricultural Economics Article Awards from the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association and the Quality of Research Discovery Award from the European Association of Agricultural Economists. He is the cluster lead for socioeconomics and ethics in the AI Institute for the Food System (AIFS). He blogs regularly at https://agdatanews.substack.com/ on topics related to agriculture, economics, and data. In July 2024, he will join the UC Berkeley faculty as a professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

Is renewable diesel a sustainable approach that can scale? Where do the oils and fats come from? Are there sufficient sources of oils and fats to grow to 100% across the US? I imagine that oils and fats aren’t just going to the landfill and already have some useful uses, is there an excess of oils and fats for some reason? Are we going to lose some other beneficial use of these or experience higher prices on something?

Great job on the median projections -the wide range is a bit wide to be believable (useful).

Given the recent scientific study of the causal relationship of atmospheric temperature and CO₂ concentration and its finding that “it is the increase of temperature that caused increased CO₂ concentration”. I wonder if any more or less biofuel volumes would be available if the LCFS policy shifted from CO2 reduction to petroleum reduction. I suspect in this alternative scenario both projections total demand and perhaps biofuels would not be impacted?

Click to access CausalityApplications_v3.pdf

Great job, as always, laying out the projections.

Great work and projections I generally agree with the median projections -the wide bands are huge.

If the newly published scientific findings on the causal relationship of atmospheric temperature and CO₂ concentration and the finding that “the increase of temperature that caused increased CO₂ concentration” survives further scientific debates – I suspect that the LCFS program would change emphasis from CO₂ reduction to petroleum reduction volumes?? I wonder if there would be any more renewable fuels available in that alternative policy scenario. And if the projections would not be changed in a non-CO₂ reduction emphasis policy.

Click to access CausalityApplications_v3.pdf

There’s pretty much a ceiling on potential renewable fuel production nationally. For example, the natural gas utilities believe they can be saved by RNG production (which competes with transportation uses), but the upper limit is less than 5% of total U.S. gas use.

California probably has the highest diesel prices in the country. Is it possible these findings are skewed by truckers buying fuel out of state?

Eventually getting rid of petroleum diesel use in California is a great prospect — not only for reducing GHG emissions, but criteria pollutants as well. Signficantly reducing Nox and particulate matter in general is very good, but it could be a godsend for places like the San Joaquin Valley, the inland empire, and the Alameda corridor leading from the Ports of LA and Long Beach. As a long-time critic of the LCFS, I commend the role it played in this switch. That said, I’m still inclined to agree with past critics such a Robert Stavins and Chris Knittel that LCFS for ligher-duty, non-diesel vehicles is largely a waste of money when it comes to getting bang-for-our-buck GHG emissions reductions.

What are the criteria pollutant emissions from green diesel vs petroleum diesel?

Renewable diesel is a diesel fuel that is derived from non-petroleum renewable resources such as vegetable oils and animal fats, and meets CARB motor vehicle fuel specifications. It is considered a “drop-in” fuel that can be used as a diesel fuel in California “neat” (without blending) or blended with conventional petroleum-based CARB diesel in any amount, and used with existing infrastructure and diesel engines. Greenhouse gas emissions from the production and use of renewable diesel in diesel engines are generally significantly lower than those from the production and use of conventional CARB diesel. Additionally, current knowledge indicates that the use of renewable diesel in diesel engines without advanced emissions control systems results in reduced tailpipe emissions of particulate matter and nitrogen oxides (NOx), both criteria pollutants, in comparison to conventional petroleum-based CARB diesel.

https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/CARB/bulletins/2eca366

Also see: https://www.cantwell.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Biodiesel%20Environmental%20Justice%20One-Pager.pdf

The LCFS is a well-intentioned but misdirected policy. We have little way of knowing whether the emphasis on emissions from petroleum fuels is more or less expensive than, for example, regulating paper and steel mills, fertilizer production or electricity generation. The goal of reducing GHGs is so important we cannot afford to risk pursuing expensive options when less expensive options may be available. We should be harvesting the lowest hanging fruit first. If CI (carbon intensity) is to be the emission standard, let’s impose a single intensity standard applicable to all emitting sectors – tonnes emitted per $million of value added. With this performance standard, those producing the most value andthe least emissions will be rewarded with marketable credits that only encourage them to find more low-cost emission reductions. This market mechanism will ensure the path to net-zero is as efficient as possible whereas the status quo of creating a unique standard for each sector risks taking the a more and perhaps most expensive path. Section 111 of the Clean Air Act already allows EPA to create performance standards for categories of stationary sources. A “value added” performance standard could be applied to a single category of stationary sources emitting more than, for example, 50,000 metric tonnes per year. A parallel standard for transportation fuels might be possible under EPA’s existing mobile sources authority. If we define acceptable performance as being the same for the entire economy, the most economic solution will likely result.

Bob Neufeld

A very thorough outline however ..

This discussion strikes me as an exercise in “Moving the chairs around on the Titanic”s0-to-speak. The false LCFS solution of promoting the burning of renewable diesel isn’t the future of trucking in California or the wider world..

Efforts end our addiction to burning fuel in horribly inefficient, polluting internal combustion vehicles are:

https://www.nikolamotor.com/tre-bev/

https://www.nikolamotor.com/tre-fcev/

JG

I understand this article to say the biofuels produce 1/2 the greenhouse gasses as petrofuels. OK, this is good, but don’t we still have to pretty much eliminate all greenhouse gasses? So this would be just a short term solution until a more viable long term solution becomes available?

Good question. What about diesel electric? Put solar panels on top of all the trailers connected to lithium batteries in the tractors. Drive the wheels with electric motors that are powered by a smaller diesel engine using non-petroleum diesel fuel and the solar panels both working together to charge the batteries plus dynamic breaking. Deisel locomotives have been doing this for years just minus the solar on every box car but that could also be a future for railroad emission and CO2 controls. The higher fuel costs, the more we will find alternatives.