Offset Me Not

Are voluntary carbon offsets really that different from other forms of corporate social responsibility?

A couple years ago, as part of a blog about offsets, I posed the following question: Why does there seem to be so much outrage over the fact that firms claim carbon offsets when spending money to protect forests, but there are almost no complaints about the fact that firms can deduct from their taxes similar contributions to, say, the Nature Conservancy? The periodic story about how offsets are terrible are almost as much a staple of environmental news as stories about how high gas prices are in California. (Well, not really. Nothing beats a gas price story – or blog post).

Now, I can see the case that the “non-additionality” of carbon offsets deserves a lot of scrutiny when those offsets are used for compliance in a mandatory carbon market, such as the European ETS, or California’s cap-and-trade system. In these settings, more offsets hypothetically allow for additional verified emissions under a cap. If those offsets are not “real,” this leads to higher emissions. As I have argued in the past, even this case is weaker than many think, since in almost every carbon market the principle of TCINRAC (the cap is not really a cap) applies.

But even this, somewhat diluted, criticism does not really apply to the voluntary offset market, where offsets are not used for compliance with a mandatory cap. Voluntary offsets are sometimes marketed to reduce guilt, or used by firms to advance their internal carbon neutrality goals. Because they are not linked to any specific regulatory requirement, the voluntary offset market is more sprawling, and less regulated than the market for offsets used for compliance with the ETS or California’s program.

My own personal view is that it is hard to get too upset about almost any voluntary spending directed at improving public goods. Therefore, while there may be a lot of reasons to be skeptical about exactly how many tons of carbon dioxide are truly being reduced by some offset projects, I find it hard to be overly exercised about the practice. Eye-roll? Yes. Outrage? Not really.

The case for a difference between an offset and other forms of corporate social responsibility goes something like this. “These guys are claiming to offset XX tons of CO2,” or “this company claims to be carbon neutral, but it’s all BS because … offsets.” In other words, the sin is not in throwing money at arguably inefficient, if not outright dubious, forms of social responsibility, but from claiming some kind of moral high ground in the process. However, claiming moral high-ground is not a new practice in corporate America, and I thought most of us were appropriately cynical about such things. The difference with offsets that seems to set off many in the environmental community appears to be the quantification of the virtue provided by the public minded purchaser of offsets. Something along the lines of “You’re not really saving 100 sea turtles, only 35!!”

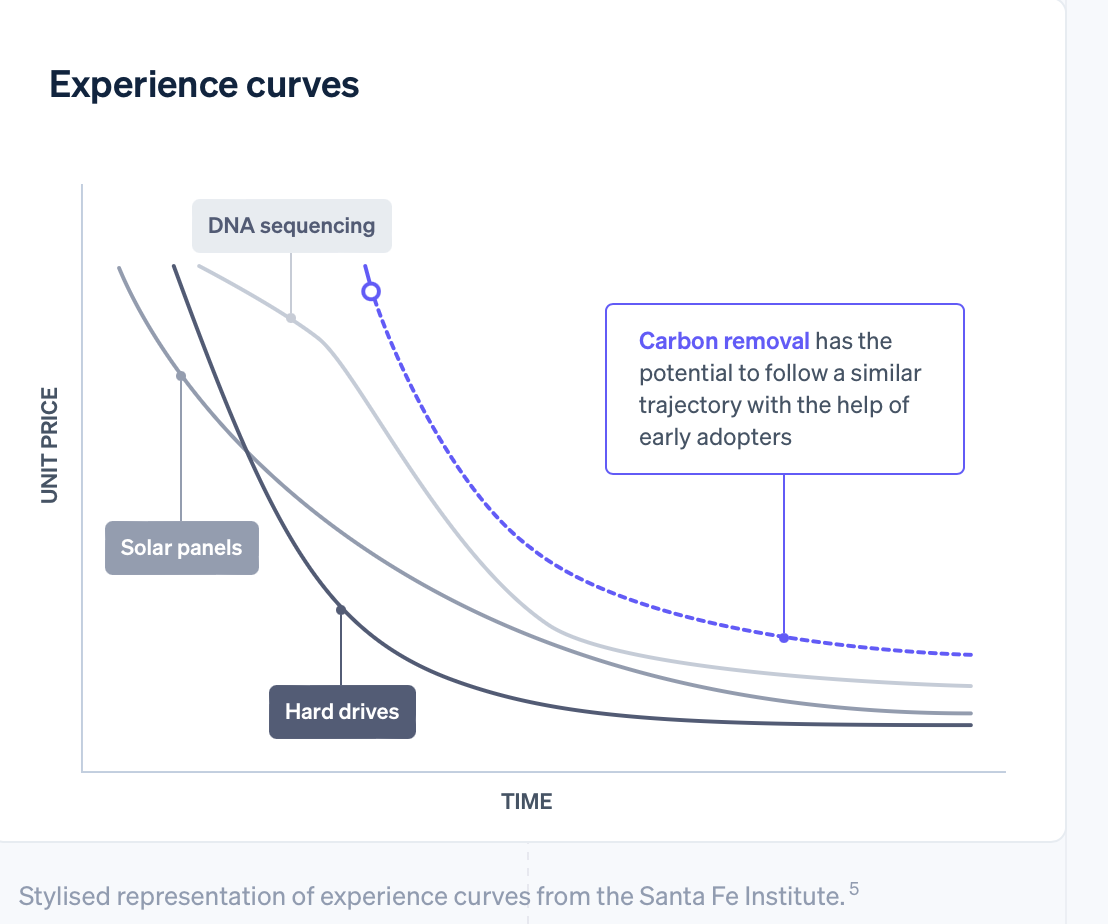

This leads us to the interesting case of Stripe Climate. Several years ago a reporter pointed out to me that Stripe, the payment processing firm, was facilitating the support of a raft of carbon removal initiatives. What was so refreshing about this was that Stripe was emphasizing the importance of funding high risk, high reward technologies, using cool graphics about learning curves, and explicitly avoiding claims to offset any specific amount of CO2. This initiative is still going strong, under the branding of Climate Commitments. Stripe now publicizes this initiative as “the right choice for businesses that … don’t need to buy a specific number of tons to meet a climate target.”

Stripe now also runs a second initiative called Climate Orders. This is for “businesses that need to buy a specific number of tons to meet a climate target.” To be clear, these are not offsets in the classic use of the term. These are pre-funded tons to be removed from the environment through one of the carbon removal initiatives that Stripe Climate, and its subsidiary Frontier, interact with. From what I can tell, these are verifiable tons that do not suffer from the typical adverse selection and moral hazard problems associated with traditional carbon offsets.

But here’s the thing. The only firms that need to buy a specific number of tons of allowances are those regulated under mandatory cap and trade programs. All the other firms just want to buy a specific number of tons to pursue some kind of voluntary initiative, or to satisfy some environmental pledge. However, it’s quite likely that the best way to make a global impact is to not bean-count your personal, or corporate, or university emissions in a quest to live in the net-zero room.

Solving climate change will require the entire globe, not just the virtuous pockets, to eventually reach net-zero carbon. This means convincing, or coercing, the folks who don’t feel like making dramatic voluntary reductions. We’re probably going to have to do a fair amount of capture and sequestration for the rest. High risk and high reward initiatives that might, just might, get us to low-cost clean energy, or carbon removal, or even adaptation, are likely to be required. So I applaud the spirit of Climate Commitments – mobilizing publicly minded contributions towards new technologies that might make a difference on a global scale – and I wink at the contributors to Climate Orders with a little bit of an eye-roll, but not much outrage.

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, as well as subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation: Bushnell, James. “Offset Me Not” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, March 4, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/03/04/offset-me-not/

Categories

Voluntary carbon offsets are around $2 billion a year. So, not a big deal or so it seems. What is a big deal is the plans of many who are forecasting a market of $100 billion within a decade. To dismiss them as not worth worrying about ignores the widespread abuse, ineffectiveness and misallocation of resources.

Consider if all the corporations buying voluntary offsets instead directed those assets into research and development. A prime example for comparison: Delta Airlines has been one of the biggest buyers. United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby says “…the majority of them are fraud.” Kirby has committed $100 million to research and development on non-fossil aviation fuels instead.

And yes, the majority of voluntary carbon offsets are fraudulent based on the numerous analyses over the last decade well recorded by researchers and investigative groups. Even “regulated” offset markets are flawed. A good starting point was the EU evaluation of the “official” offsets under the Kyoto Agreement. Over 80% of over 5500 projects could not emissions reductions. And the EU terminated use of the offsets to meet cap and trade obligations.

Scan the summary report that contains most of the research and investigations over the last decade at: https://web.sas.upenn.edu/pcssm/news/carbon-offsets-are-unscalable-unjust-unfixable-joe-romm/

To ignore the scandal of endorsing offsets is to put at risk the potential to convince others of the need to consider serious market-based carbon pricing (e.g., a carbon tax). If you are an advocate of carbon pricing, you should disavow voluntary offsets.

Most concerning is the lack of mention in the blog about the corrosive effect on already weak institutions and the serious corruption in emerging economies. Note the most recent voluntary carbon market agreement between Blue Carbon (UAE) and numerous African countries to turn millions of hectares of tropical forests into carbon offsets. Too many political leaders in tropical emerging economies are only too happy to get on-board and share the developed countries corporate funding.

Advocates of carbon markets should should take a closer look at the voluntary carbon markets and explain how offsets can work when the incentive structure for all participants is to do a deal regardless of the merit. Everybody wins and the climate loses. It has been 20+ years of plans to reform the mess and it is no closer.

If California ARB can’t get it right in a regulated framework (Haya), why will it be done properly in an unregulated market? Ultimately, all the financial securitizers (Mark Carney et al) won’t (and can’t) take a responsible role for what is going on. Neither will the Big Green NGOs pursuing voluntary carbon offsets.

The costs of this policy, contrary to the author’s view, far exceed the illusory marginal benefits.

I would argue that outrage related to the voluntary carbon market is not misplaced. The author overlooks the issue of mitigation deterrence. The mere existence of cheap carbon offsets displaces much-needed investment in direct emissions cuts. If organizations can theoretically achieve net zero targets through the purchase of cheap voluntary carbon offsets, they won’t be pressured to invest in more expensive decarbonization. I’ve seen this firsthand at my own organization, a large environmental NGO. The executive leadership wants the organization to be able to claim net-zero, but balks at the amount of investment and the behavioral changes that would be necessary to actually decarbonize. Carbon offsets provide them with an easy out.

I think an important change needed then to decrease reliance on offsets is to acknowledge that “net zero” target years are unrealistic given current technology, legacy infrastructure, feasible new technology production and limits on changes in social, cultural and behavioral parameter. But so long as we see claims of reach net zero by 2030, we will see offsets as the part of the only feasible path.

Even the invisible hand gets tired of patting itself on the back for performative carbonism… The real challenge isn’t just buying our way to virtue with offsets (as the European experience with ETS showed); it’s in genuinely tracking, monitoring and reducing lifecycle emissions and imposing fines that are reflective of the social cost of carbon to deter Big Oil and the likes.

My thesis looked at neighborhood level particulate pollution in CA, and surprisingly enough, we don’t even do a great job at monitoring (let alone reducing) PM2.5 pollution in our communities.

On the one hand, I agree with Jim “that it is hard to get too upset about almost any voluntary spending directed at improving public goods” even if the voluntary offset market only leads to modest gains. They are still gains that perhaps would otherwise not have been made.

An August 2023 NYT op-ed by Peter Coy that focused on a study of voluntary offset markets by Barclays acknowledged as much:

“The Barclays report focused on the voluntary carbon market. That’s the one that companies such as Microsoft and Salesforce are using to help reach their goals of net-zero carbon emissions. If they can’t reduce their own emissions all the way to zero, they can go into the market and buy credits from someone in, say, Brazil who has earned them by planting trees to soak up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The voluntary carbon market can be a valuable mechanism for directing investment to developing nations that need help in the fight against climate change.”

However, as Coy further notes, “Gresham’s Law says that bad money drives out good…. According to the Barclays report, the price of carbon credits has fallen to around $2 per metric ton of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, down from around $9 early last year. That’s not because the cost of reducing emissions is really just $2 a ton. It’s because buyers don’t trust the quality of the credits.”

In this regard, Coy cites comments from Mark Kenber, the executive director of the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative”

“A separate carbon market for voluntary projects made sense in the early years of fighting climate change at the corporate level, when any kind of effort was better than nothing. But it should be a second-best solution now that all countries have ostensibly committed to reducing their carbon emissions. The fact that we are in 2023, some 35 years after international negotiations started, still talking about voluntary action is a sign that we have collectively failed,” Kenber said.

I don’t necessarily agree with Kenber’s strong inference that “volutnary action is a sign of failure.” I generally agree with Jim that if a company doesn’t NEED to by credits but just want to do some degree of good, there’s nothing wrong with that in itself. However, it seems that that the extremely low price of credits in the voluntary markets compared to the EU ETS, and to a lesser extent, California’s market, creates a drag on the carbon credit prices in “official” government markets given the ubiquity of voluntary markets and there inherent flimisness.

Indeed, Coy also noted that the “Barclays report said that the voluntary carbon market — with its inconsistency and lack of regulation — is ‘undermining the Paris Agreement process by casting doubt on the legitimacy of country-level emission reductions since these are also being claimed by corporates in other countries.’”

I believe that voluntary actions can still be beneficial, but we need a better accounting system for those actions, and perhaps limits, to help “official markets” function more effectively.

I neglected to add the link to Peter Coy’s op-ed in my previous comment, so here it is:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/23/opinion/climate-change-carbon-offsets.html

Seriously, is there really any coherent economic rationale for offsets? The basic argument is that a marginal ton of GHG reduction has the exact same environmental benefit whether it’s achieved by not cutting down several dozen trees or by not consuming one MWh of coal-powered electricity, so why forego that 1 MWh if it’s cheaper and easier to not cut down some trees? The flaw in that argument is that we can’t avoid climate catastrophe with marginal emission reductions; we need to get to net-zero or net-negative emissions. When you buy offsets, you aren’t reducing the cost of decarbonization; you are only deferring costs that you or somebody else will need to pay sooner or later. Procrastination is not a viable strategy for long-term cost minimization.

We’re not going to offset our way to carbon neutrality. We need to make foundational capital investments in a new energy economy, which will be expensive in the short term but can return positive investment dividends as well as climate benefits for perpetuity. The sooner we invest, the sooner the dividends start accruing. Offsets, carbon trading, banking, and California’s entire caps-and-standards regulatory infrastructure are not grounded on an effective investment strategy or any rational economic foundation. Cap-and-trade should be abandoned because “the cap is not really a cap” and we should stop pretending that it is. The cap is expressly preempted by the price ceiling, which represents the limit of what we are able and willing to pay for climate change mitigation; and as long as the price ceiling is below the social cost of carbon (currently estimated by EPA at about $200/ton), there is no economic justification for setting carbon prices lower than the price ceiling. Don’t try to cap emissions and minimize prices; instead cap prices and minimize emissions. Don’t use carbon pricing to extract taxation revenue from regulated industries; use it to finance decarbonization of those industries and to make clean energy affordable. Provide additional opportunities for clean-energy investment, e.g., through bond auctions for infrastructure projects. Individuals and companies who want to “offset” their emissions can do so by bidding a negative interest rate and reinvesting their dividends in more zero- or negative-carbon infrastructure.