Federal Swings in Water Regulations Dramatically Changed Policy for Energy Projects

This week’s blog post is coauthored with Hannah Druckenmiller, Simon Greenhill, David A. Keiser, and Sherrie Wang.

Changing rules have altered which energy developments are subject to the Clean Water Act, a machine learning analysis finds.

The 1972 Clean Water Act protects the “waters of the United States” but does not precisely define which of the 3 million US stream miles and 120 million acres of US wetlands this phrase covers. Instead, presidential administrations and the Supreme Court have used qualitative language to describe what constitutes the “waters of the United States,” then the Army Corps of Engineers determines whether the Clean Water Act regulates individual sites on a case-by-case basis. As a result, the exact coverage of the Clean Water Act rules is a moving target.

Prior academic and policy analyses assumed that streams and wetlands sharing certain geophysical characteristics were regulated, without scrutinizing data on what was actually regulated—an approach the Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers called, “highly unreliable.” For example, some Clean Water Act rules change regulation for “isolated wetlands” or “ephemeral streams.” Which exact water bodies do such phrases regulate or deregulate? The Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers summarize, “EXISTING TOOLS CANNOT ACCURATELY MAP THE SCOPE OF CLEAN WATER ACT JURISDICTION” (formatting in original).

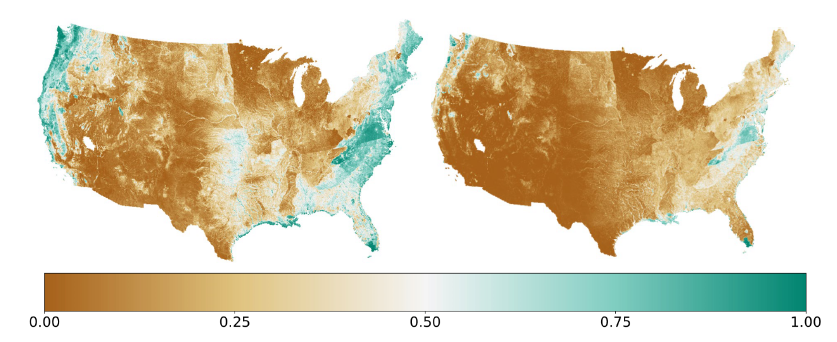

Our new research in Science and a new EI Working Paper uses machine learning to more accurately predict which streams and wetlands the Act protects. A 90-second video explains our research and an interactive map lets users see its predictions. We found that a 2020 Trump administration rule removed Clean Water Act protection for one-fourth of US wetlands and one-fifth of US streams, and also deregulated 30% of watersheds that supply drinking water to household taps.

Source: OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4, created January 12, 2024.

Using machine learning to understand these rules helps decode the DNA of environmental policy. It finally lets us understand what the Clean Water Act actually protects, in practice.

We trained a deep learning model to predict 150,000 jurisdictional decisions by the Army Corps. Each Corps decision interprets the Clean Water Act for one site and rule. Each site typically represents a development project like construction of a solar power plant, decommissioning of a coal-fired plant, or expansion of a factory, road, or housing development. To predict these decisions, we use 34 geophysical layers including aerial imagery, wetland and stream maps, groundwater and soil data, climate, elevation, and others. The model predicts regulation across the US under two interpretations of the Clean Water Act –the Supreme Court’s 2006 Rapanos ruling and the Trump administration’s 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR).

This game of regulatory ping-pong has staggering effects on environmental protection. Our research found that the 2020 NWPR deregulated 690,000 stream miles, more than every stream in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas combined. Wetlands provide economic value by decreasing water pollution, preventing floods through acting as a sponge, and providing other ecosystem services. As one way to quantify these impacts, we applied a recent analysis of wetlands and flood mitigation to conclude that the wetlands deregulated under the 2020 rule provided over $250 billion in flood prevention benefits to nearby buildings.

Maps: Probability of Clean Water Act regulation under Different Rules. Green areas have high estimated probability of regulation; brown areas have low estimated probability of regulation.

- 2006 Supreme Court rule (Rapanos) B. 2020 White House Rule (NWPR)

—

Impact on Energy Projects

While the Clean Water Act targets water pollution, the law ultimately restricts land use. Clean Water Act regulation affects development involving regulated waters because construction activities deposit dredge and fill material (e.g., soil) into regulated waterways, which is considered pollution.

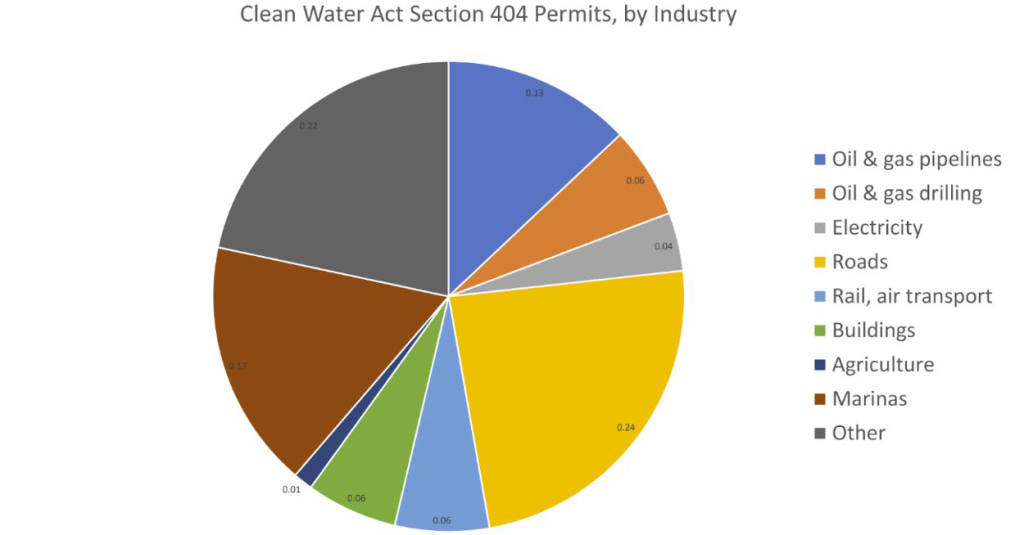

For example, the Clean Water Act regulations we study may affect a desert solar project where a stream flows a few days per year, a gas pipeline crossing historic wetlands to reach a new fracking project, or a road that crosses isolated marshes. A fourth of projects permitted under the regulations we study involve oil, gas, and electricity, and another fourth involve roads and transportation.

Source: EPA (2021)

Land use restrictions, such as through the Clean Water Act, could slow both the energy transition and fossil fuel investments. Solar and wind projects, and associated transmission lines, require enormous amounts of land. Some land needed for renewable energy investments face restrictions for environmental and other reasons. Of course, land use restrictions for energy investments could be justified by their externality benefits in other domains (e.g., preventing water pollution).

Two examples illustrate the breadth of potential impact. The 250 MW Moapa Southern Paiute Solar Project is located in the Mojave desert northwest of Las Vegas, within the Moapa River Indian Reservation. It was the first US utility-scale solar project located on tribal lands. The project area covers many ephemeral streams and desert washes. Project developers requested the Army Corps to assess 51 stream areas and determine whether the Clean Water Act protected each (results here in 2016 and here in 2021). The Army Corps concluded that these streams are not jurisdictional under either the 2006 Rapanos rule or the 2020 NWPR rule, primarily because they do not eventually flow into navigable waters.

Solar Power in the Mojave Desert. Source: Wikipedia

The Bremo coal-fired power station in Central Virginia began a decommissioning process in the late 2010s near streams and potential wetlands. Decommissioning, including removing coal ash, may pollute these waterways. Developers asked the Army Corps whether the Clean Water Act regulated affected waters. The Corps determined in 2021 that 80% of the involved streams and wetlands were regulated. Due to this regulation, the project required an additional permit involving public notification, analysis and pursuit of alternative project designs that minimize hydrological impact, paying for restoration of offsite streams and wetlands to offset project impact, and other regulatory steps.

Saving Time and Money

The study estimates that the machine learning model’s predictions could save over $1 billion annually in permitting costs for developers by providing immediate estimates of the probability that a site is regulated, rather than waiting months through the permitting process.

The methodology used in our paper will also be valuable for understanding more recent policies. After this study’s data, the 2023 Biden White House rule expanded Clean Water Act jurisdiction and the Supreme Court’s 2023 Sackett decision then contracted it. Once Sackett is fully implemented, the methodology used in our paper will also be valuable for understanding more recent policies.

This blog describes the following paper: Greenhill, Simon, Hannah Druckenmiller, Sherrie Wang, David A. Keiser, Manuela Girotto, Jason K. Moore, Nobuhiro Yamaguchi, Alberto Todeschini, and Joseph S. Shapiro. 2024. “Machine learning predicts which rivers, streams, and wetlands the Clean Water Act regulates.” Science 383(6681): 406-412. The authors are inventors on a patent pending which covers commercial applications of the machine learning algorithm. The license freely allows use for research and other noncommercial purposes.

Follow us on Bluesky and LinkedIn, as well as subscribe to our email list to keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation: Shapiro, Joseph S., Druckenmiller, Hannah, Greenhill, Simon, Keiser, David A. , and Wang, Sherrie. “Federal Swings in Water Regulations Dramatically Changed Policy for Energy Projects” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, February 5, 2024, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2024/02/05/federal-swings-in-water-regulations-dramatically-changed-policy-for-energy-projects/

Categories

This article provides a comprehensive and insightful analysis of the significant impact of federal swings in water regulations on energy projects. The authors delve into the intricate dynamics of the Clean Water Act and how changing rules have reshaped the regulatory framework governing streams and wetlands in the United States. By employing machine learning techniques, the research offers a novel perspective on the practical implications of these regulatory shifts, shedding light on the complex interplay between environmental policy and energy development.

What sets this piece apart is its meticulous examination of the real-world implications of regulatory changes, particularly in the context of energy infrastructure projects. The case studies presented, such as the Moapa Southern Paiute Solar Project and the Bremo coal-fired power station decommissioning, vividly illustrate the far-reaching consequences of regulatory decisions on land use and project development. Moreover, the article underscores the importance of leveraging advanced analytical tools and staying abreast of evolving policies to navigate the regulatory landscape effectively.

Overall, this article serves as a valuable resource for policymakers, industry professionals, and environmental advocates seeking to understand the intricate relationship between water regulations and energy projects (the one like to check FESCO Bill). Its rigorous analysis and insightful commentary offer valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities inherent in balancing environmental conservation with energy development in the modern era.