45 years ago, mass produced computers exploded onto the global stage as a harbinger of the digital future. And they've never really lost that futuristic shine, with every major announcement in hardware or software touting how the latest product will shape the world of tomorrow, albeit most likely in the form of a new phone or cloud service. But while the industry continues to look forward, more and more people are looking backward over those 45 years, and further, to the systems of the past.

Academic historians, collectors, gamers, and homebrew computer makers have all heightened interest in so-called retrocomputing, which we're going to broadly define as focused on creating a practical encounter with older systems, whether it be through emulators, replicas, original hardware, or hybrid approaches that combine the old and new. These direct experiences can provide insight (and pleasure) that no amount of historical description can match, especially when descriptions are thin on the ground, even for computing experiences that influenced entire generations. Most software was treated in its time as ephemeral, and hardware often received even less attention. Thus, some of the fascination of retrocomputing lies in its detective element, with systems reverse engineered with modern tools, sometimes down to the silicon level, and old design documents unearthed from retiree's attics.

Retrocomputing has become so popular that some old systems have become very pricey: an original Apple I might set you back almost US $1 million. And fake old chips are common, with unscrupulous sellers sanding off component numbers from integrated circuits and replacing them with more desirable ones. But for this guide, we're highlighting less expensive ways to get into retrocomputing in roughly historical order, mainly through faithful replicas or hybrid systems that can provide the hands on feel without breaking the bank. Note that many of these products are made by small manufacturers, so always check availability!

The PiDP-8: A Miniaturized Minicomputer

Stephen Cass

In 1965, the style was groovy, even when it came to minicomputers. Digital Equipment Corportion's PDP-8 was noted not just for its small size (it could be transported in the back of a VW Beetle!) and relatively small price tag (just US $18,500!), but also for its front panel with its colorful orange and yellow switches and tastefully diffused blinkenlights. And now you can get a PDP-8 small enough to fit on a shelf for just $190 from Obsolescence Guaranteed. The heart of this replica is a Raspberry Pi running emulation software, so it can also double as a 1970 PDP-11 (and a home media server). Check out our full write up—and personally I thought it was worth it just to play Spacewar! with the original code!

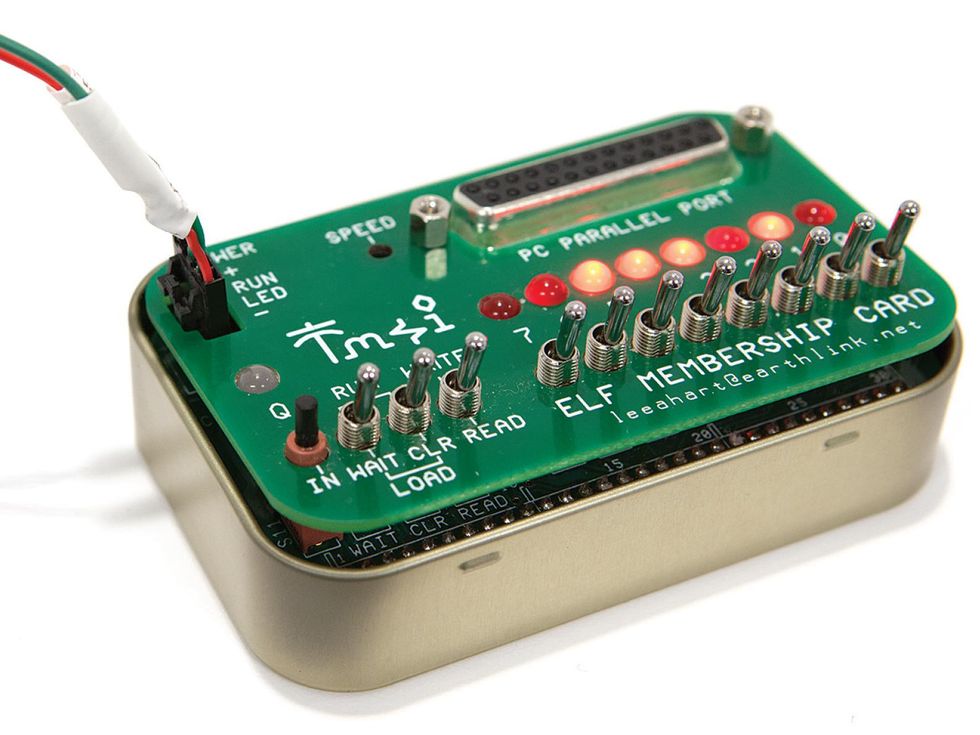

Get An ELF In Your Pocket With The 1802 Membership Card

(Previous version pictured)

Randi Klett

The RCA CDP 1802 was the first CPU designed for home computing, and in a different world its creator Joseph Weisbecker would be as well known as Steve Wozniak is today. One of the earliest homebrew computer designs was for the Cosmac Elf, the plans for which were published in 1976 in Popular Electronics by Weisbecker. One of the best reproductions of the Elf is Lee Hart's US $89 Membership Card kit, which compresses an Elf into two circuit boards that fit into a Altoids tin. IEEE Spectrumhas a full write up on the kit, but since that article was written Hart has come out with a revised version that's even easier to connect to a modern PC, so you can download programs without needing to toggle them in bit by bit!

All Aboard the Altair-Duino

Randi Klett

The Altair 8800 wasn't the first personal computer (that honor likely goes to the Kenbak-1), but it was the first commercially successful one, inspiring many, including a young Bill Gates and Paul Allen to found a little startup called Microsoft. Chris Davis makes a terrific replica kit, the Altair-Duino. The Altair-Duino runs a clock-cycle accurate emulation of the Altair 8800 running on an Ardunio Due connected to a replica panel that duplicates all the lights and switches of the original. What's especially nice is that the kit comes with an enormous amount of software preloaded, and can be accessed using a wireless terminal connection or plugged into a VGA monitor (the kits runs from $160 to $250 depending on the options chosen). I've have an early version of this kit running in my office at Spectrum and it never fails to catch a visitor's eye. The current "pro" version features a blue acrylic addition to the case that makes it look even more like an original Altair.

Wichit's Choose Your Own CPU

Wichit Sirichote has created a whole line of retro microprocessor-based single-board computers. Sirichote's elegant design includes a keyboard, 7-segment display and RS-232 interface, and are easily expanded to include an LCD character display. Sirichote sells them through eBay, and they cost between US $130 and 175. Classic CPUs available include the Intel 8088, the TMS9995, the RCA 1802, the 6502, and the Z80. System busses are easily accessible if you want to add extra hardware. I have the 6502 kit, and I've found the built-in monitor very easy to use, including when downloading code from a PC via its RS-232 serial port.

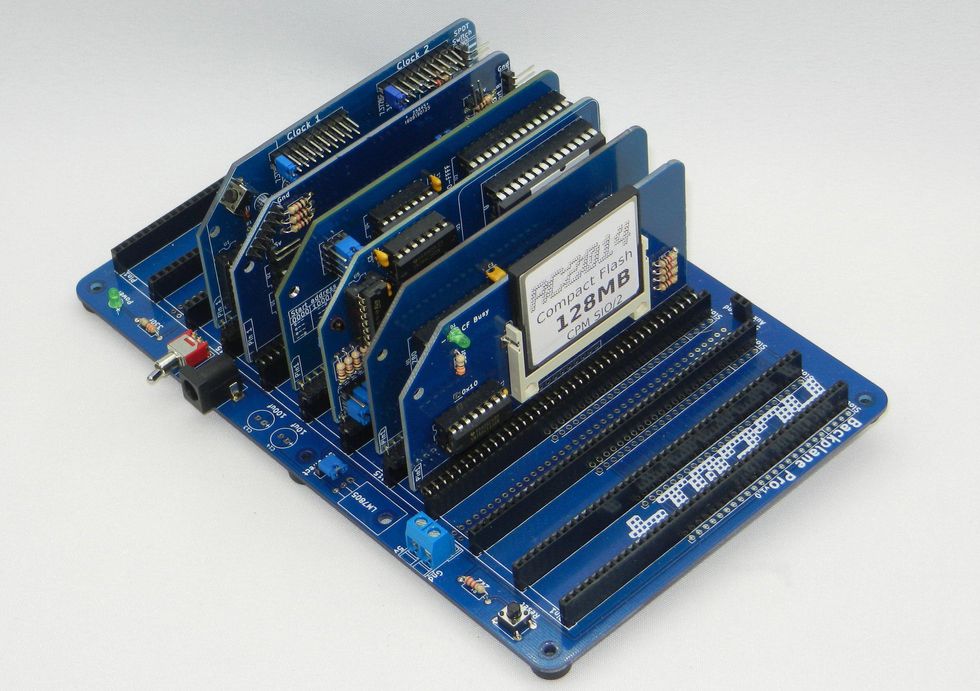

Get The Z Factor With An RC2014

This is the one entry in our retrocomputing gift guide I haven't tried myself: I've never been a Z80 guy, being more influenced by the 6502-based BBC Microcomputer than the Z80-based ZX Spectrum, which were the two most popular British-designed computers I had access to in the 1980s. But for several years, I've been looking covetously at the rich ecosystem that's sprung up around the Z80-based RC2014, another British-designed computer which features a backplane with slots for expansion cards (kits are $77 to $199 depending on how many cards you want to start with). People have been making all sort of cards for the RC2014, including a speech synthesizer, hard disk interface, and a graphics and WiFi card.

The 6502 Strikes Back With The Planck

Stephen Cass

The success of the Z80-powered and backplane-centered RC2014 recently inspired Jonathon Foucher to do something similar for the 6502 CPU—previously 6502 aficionados tended to favor single board computers. But Foucher's Planck computer has six expansion slots, and a really nice clock stretching scheme that allows the CPU to run as fast as 12 megahertz most of the time, and then slow down if it's talking to a card with older components that can't handle those speeds. The basic kit relies on a serial interface, and you'll need your own EEPROM programmer to flash the default Forth operating system. Foucher has several expansion cards already available, such as a PS/2 keyboard adapter and a driver for LCD character displays, and like the RC2014, blank prototyping cards are available if you want to try making your own card: right now I'm soldering my kit together and noodling on a design for a memory bank switching card to go beyond the 64 kilobytes that most 8-bit systems can address.

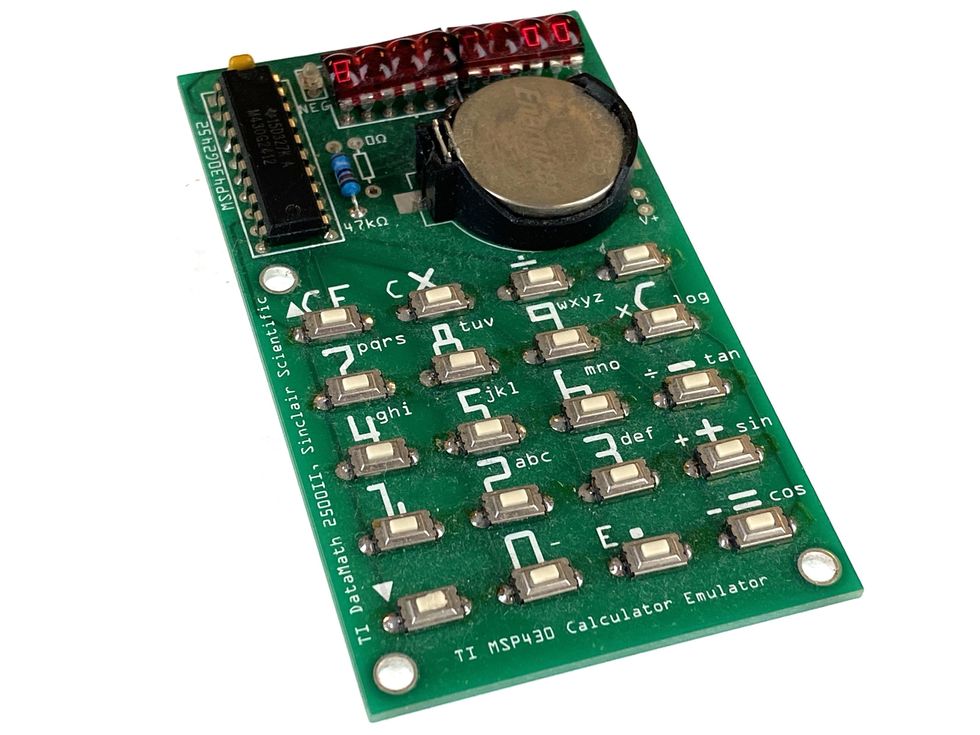

Be Scientific With This Sinclair Classic

Stephen Cass

If you want a retrocomputing experience that's small enough to fit in the smallest pocket, then Chris Chung's US $79 TI MSP430 Emulating Calculator Kit is just the thing. It actually emulates two classic calculators, complete with iconic 1970s-style red bubble 7-segment LEDs, and with the same footprint as a credit card. The two calculators are the TI Datamath 2500 and, far more interestingly to us, the Sinclair Scientific. The Sinclair Scientific wins for two reasons: first, the tricks Sinclair used to make a functional scientific calculator using a CPU that was designed for much more primitive applications are fascinating. Second, the story of how Ken Shirriff was able to figure out these tricks by reverse engineering the original chip's software by using a microscope is also amazing—full details are in our Hands On write up on the kit.

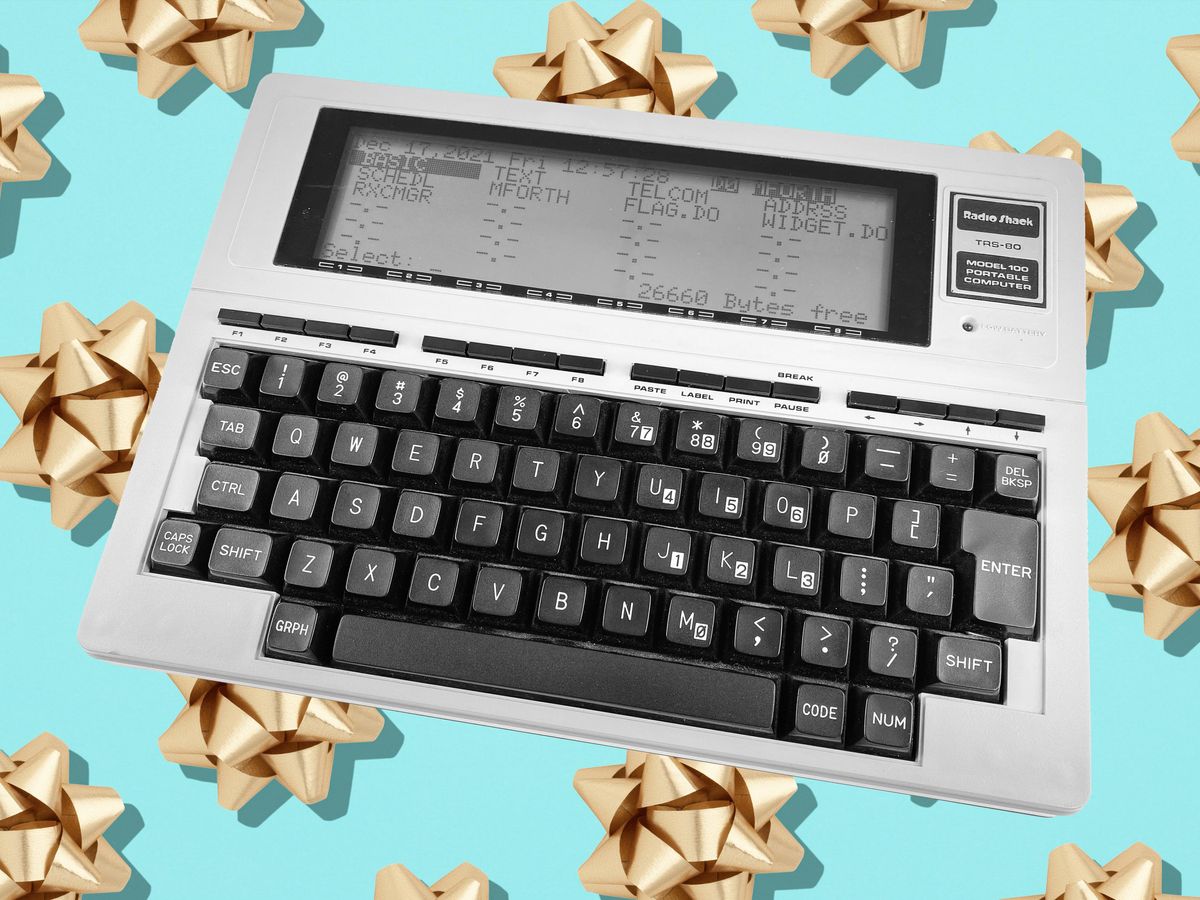

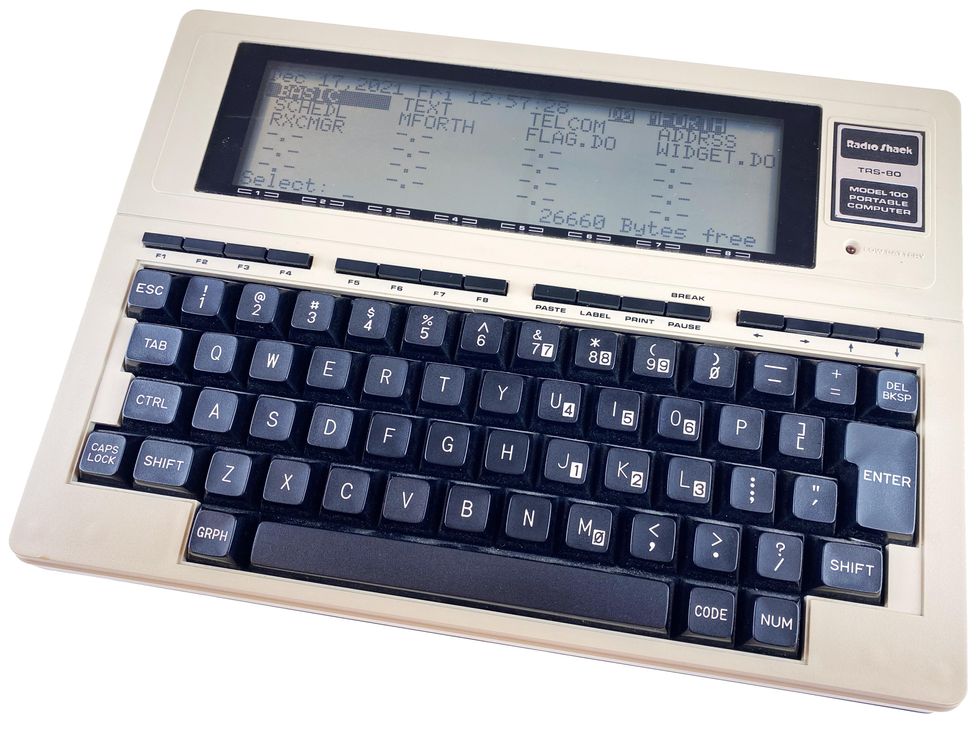

Go Vintage With The Tandy Model 100

Stephen Cass

The growth in retrocomputing has driven up the price of many classic computers and game consoles: 10 years ago, you could barely give away a Commodore 64, while today ones in good working condition often go for between US $200 and $300. But there are still some bargains to be had, so if you're looking for original tech and not just a replica, then I'd recommend trying to pick up a Tandy Model 100, working versions of which go for $75 to $200. The Model 100 was launched in 1983 and cost between $1,100 and $1,400 at the time—the high price was because it was one of the first true laptops, and had a built in phone modem and RS-232 port, making file transfers much easier than with many other 8-bit computers. The display is black-and-white 240 by 64 pixel LCD, but combined with an excellent keyboard and the easy connectivity, it was popular with the first generation of journalists to take a computer out on the road. And the Model 100 can operate continuously for about 20 hours on four AA batteries, and keep its memory alive on standby for 30 days, with an internal battery that preserves the memory between battery changes. The Model 100 came with between 24 and 32 kilobytes of memory, expandable up to 72 kb, which is limiting if you're planning on writing your next novel on one, but the active community of Tandy lovers have solutions for that, including the REX series of chips, which fit into the slot available for fitting optional ROMs. These allow you to back up and swap the RAM contents, act as additional ROMware so you can run, say, FORTH, squeeze in more text per line, compose with a better word processor, and more—I got the $85 REXCPM edition, which offers RAM and ROM options, and also runs CP/M software (like Zork!) with a nearly 4 megabyte disk drive.

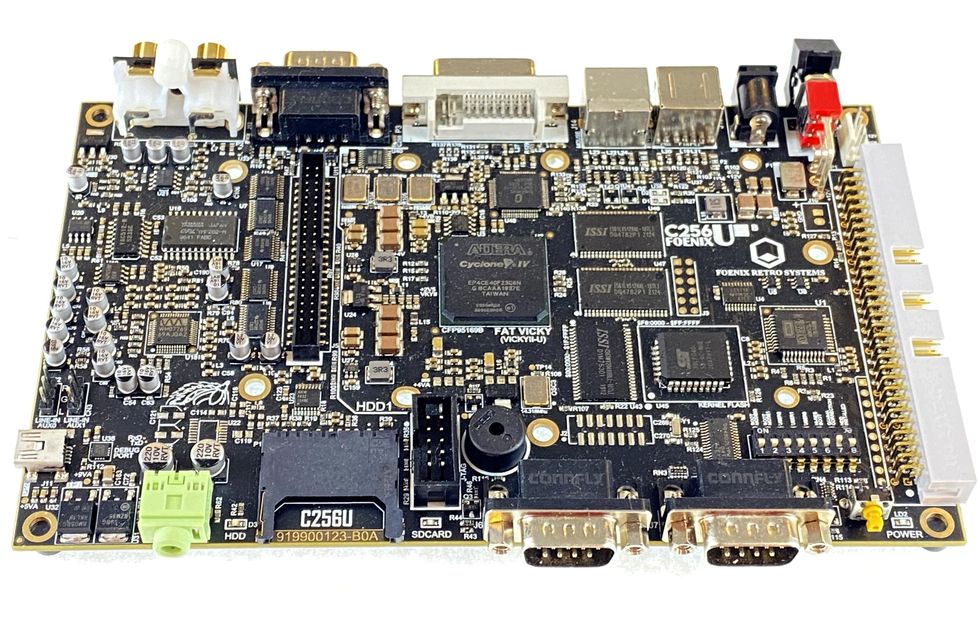

The Foenix C256: The RetroFuture Is Now

Stephen Cass

A terrific combination of old and new, the C256 Foenix line of computers is Stefany Allaire's take what might have been if Commodore hadn't stopped with the C128 in 1980s. I got the US $350 C256 Foenix U+, which comes with 4 megabytes of RAM and is based around the 16/8 bit WDC 65c816 CPU, successor to the hallowed 6502 processor. The C256 Foenix combines this classic CPU with an FPGA that provides graphics on par with the 16-bit machines of the early 1990s, and also simulates a number of classic sound chips. Other modern bells and whistles include digital video, an IDE hard disk connector, a socket for SD cards, and a USB debug port that lets you load code from a PC. If you want to try out a Foenix—and its growing collection of games and other software—before you buy, there's a Windows emulator you can download for free. Some features are still in development, like the ability to automatically boot from an SD card, but the Foenix computers are already pretty capable systems. There's also another nice twist: If you're looking for something that just turns on and a child can start programming with the keyboard immediately, a la the home computers of the 1980s, rather having to login or navigate a GUI, the C256's got you covered with it's own implementation of BASIC. And if you're looking to dabble at a more advanced level, the emulator provides a lot of support for those writing 65x816 machine code.

See It As It Was Meant To Be With A Portable Color CRT

Another gift that falls in the once-you-coudn't-give-em-away category are cathode ray tube televisions. The largest ones are too unwieldy for most people's homes, but a second-hand smaller portable CRT makes a good gift for folks into retrogaming. Retrogamers love CRTs precisely because they are not as good as modern flatscreen displays, which show every pixel perfectly. Ironically, this pixel-perfection can make older games look flat, as their graphics were designed to with the imperfections of CRTs in mind, and would even leverage artifacts for particular effects. Many emulators today now attempt to simulate CRT displays, but as color portables start at around US $60 (or less if you can find a thrift store bargain), and you can buy an adapter that will convert from modern HDMI to composite video for less than $20, why not game like its 1999?

Stephen Cass is the special projects editor at IEEE Spectrum. He currently helms Spectrum's Hands On column, and is also responsible for interactive projects such as the Top Programming Languages app. He has a bachelor's degree in experimental physics from Trinity College Dublin.