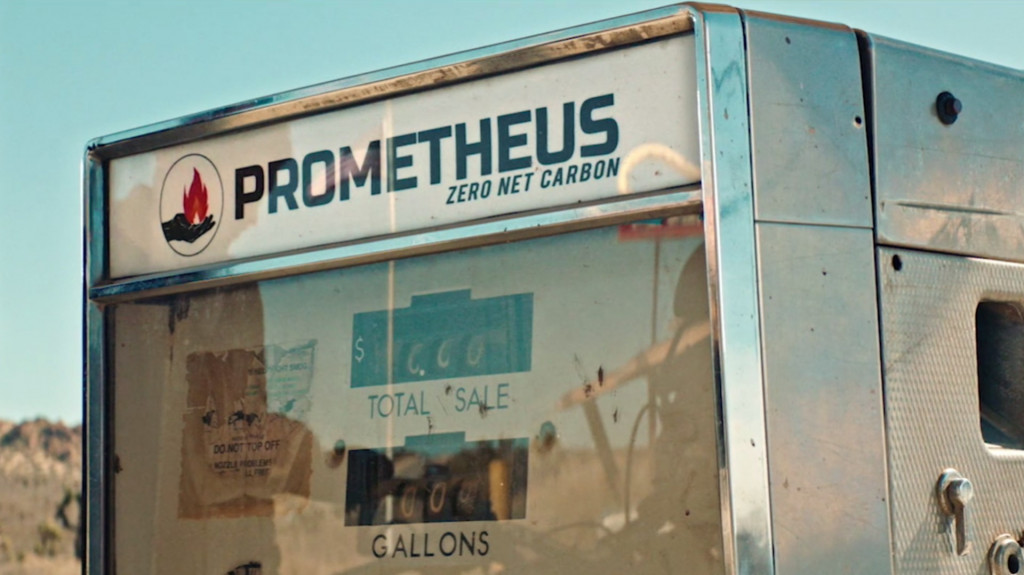

Prometheus Fuels is a California startup aiming to scale up a process that can sound remarkably simple: “We remove CO2 from the air and turn it into gasoline.”

The process, which recently has been either a holy grail or a red herring for the oil and gas industry, isn't new. But it’s been waylaid from practicality by its high cost, high energy input, and difficulties in scaling up.

For one, that electrochemical process isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. As reported by Science last month, it starts with carbon dioxide from air and water to form carbonic acid—the compound that is acidifying our oceans. It’s then converted to carbon monoxide and hydroxide, over a copper surface, with the application of electricity, and the carbon monoxide reacts with water on the copper to make ethanol. A catalyst helps produce larger fuel molecules.

Taking out the distillation

Others have gotten this far. Those hydrocarbons are produced in water, and so far extracting them—so that they can be used as fuel—has been a costly and energy intensive distillation process. The new project uses materials originally intended for water desalination and treatment, including a “proprietary carbon nanotube membrane sieve” that claims to extract hydrocarbons better while letting the water through and leaving the alcohol (fuel).

Canada’s Carbon Engineering is probably the company that’s come the closest so far to a production product. And Audi has been involved in the production of renewable diesel at a plant in Dresden run by the energy and fuels company Sunfire. Audi’s involvement began in 2015 with a synthetic diesel project that resulted in a substance called “blue crude.” Made up of long-chain hydrocarbons, it could then be refined and be mixed with conventional diesel.

Prometheus carbon-neutral fuel

As Science put it, the project and others like it aim to make “fossil fuel without the fossils.”

Carbon Engineering said in 2015 that one of its early plants could produce about 132 gallons (500 liters) a day from 1 to 2 tons of atmospheric carbon dioxide. According to the EIA, the U.S. uses about 385 million gallons of gasoline per day. Total greenhouse-gas emissions from the U.S. is about 14 million metric tons a day.

Prometheus’ founder Rob McGinnis claims that because of the less energy-intensive process, $3 is the company’s break-even price, per gallon

As the report notes, the idea has attracted some powerful investors, including $150,000 from Silicon Valley’s Y Combinator. McGinnis, in a Y Combinator pitch, said he expects the process to reach 50 to 60 percent overall efficiency at maturity. Prometheus is the first to claim that it sees the potential to produce such fuel “at a low enough cost to compete with fossil fuel.”

That’s a big improvement over previous attempts, which have required magnitudes more end energy. But it’s still no reason to churn out vehicles with internal combustion engines because we no longer have to drill, frack, or sacrifice farmland for the cause.

Napkin math on how it would compare to EVs

There’s about 33.4 kwh of energy in a gallon of gasoline. So if it takes roughly double that (66.8 kwh) to generate a gallon—and that amount is about 10 times the generally accepted amount of energy it takes to produce a gallon of gasoline (between 6 and 7.5 kwh).

![Tesla electric cars at Supercharger fast-charging site, TK [photo: Jay Lucas] Tesla electric cars at Supercharger fast-charging site, TK [photo: Jay Lucas]](https://images.hgmsites.net/lrg/tesla-electric-cars-at-supercharger-fast-charging-site-tk-photo-jay-lucas_100648832_l.jpg)

Tesla electric cars at Supercharger fast-charging site, TK [photo: Jay Lucas]

According to the EPA, the 2019 Tesla Model 3 Long Range takes 26 kwh to go 100 miles. And the EPA says that the U.S. volume-average combined fuel economy rating for 2017-model-year vehicles (the most recent data set) was 24.9 mpg. So with the energy used to produce a gallon of gasoline, you could go 10 times that in the Model 3—more than 250 miles.

Although Prometheus would use energy from renewable sources, like wind or solar, to produce its fuel, that means the fuel requires about six times the energy (in a best-case scenario) to go the same distance as an electric car.

Getting through the green gloss

Zero carbon emissions sounds great, but it doesn’t mean zero pollution. It’s different than carbon-sequestration projects, which aim to capture carbon dioxide through shared methods but store it away long-term, so it’s not problematic for the environment. Internal combustion engines would still burn the fuels and produce nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and other criteria pollutants.

Those aiming to cut their carbon footprint in vehicles are surely best served by going with electric cars. But there could be a big future for fuels like these for air travel. Prometheus last month made a deal to supply carbon-neutral fuel for Boom Supersonic, which aims to build a supersonic commercial airliner and has 30 aircraft on pre-order from customers including Virgin and Japan Airlines.

It could signal some huge marketing opportunities and, perhaps, a new era for transparency into exactly what goes in your gas tank.